Stephen Kosnar

Lima, Peru

In his late thirties and bankrupt, Henry Dunant lived in abject poverty, on occasion being forced to eat bread crusts and sleep outdoors in Paris. It is a bitter slice of one man’s history, particularly given that only a few years earlier he had founded the International Committee of the Red Cross.1

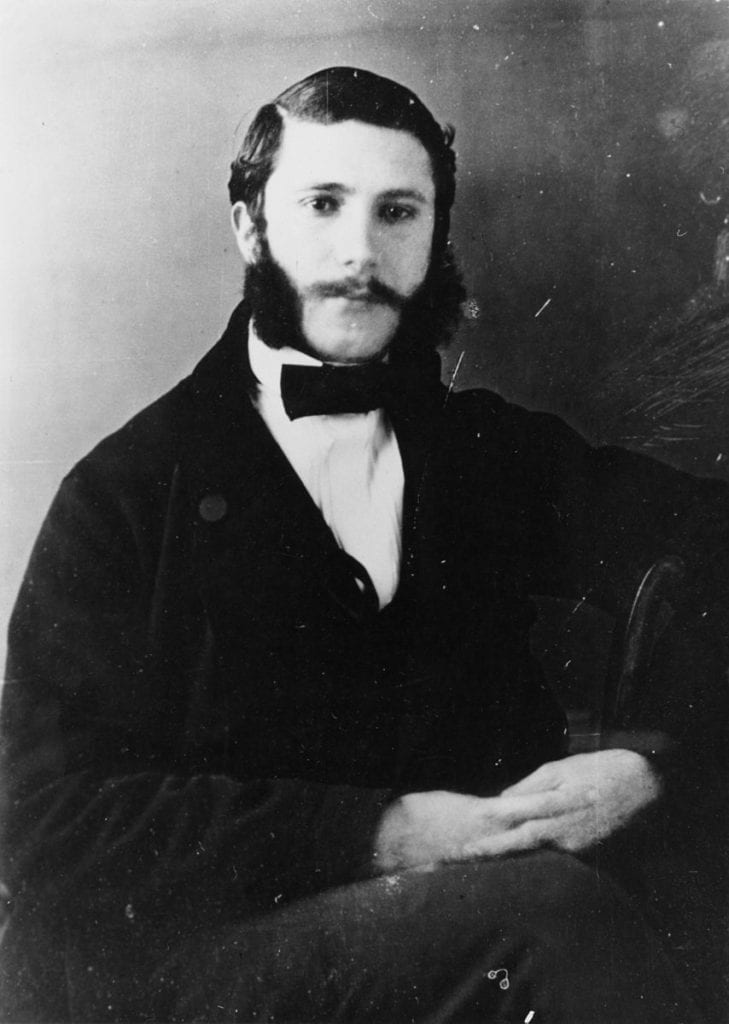

Born on May 8, 1828 in Geneva, Jean-Henri Dunant, later known as Henry Dunant, grew up under the strong moral influence of his father, a merchant and magistrate, and his mother, who encouraged him to seek out the less fortunate in society.2

By age twenty-five, Dunant, having joined the Evangelical Society after having a religious awakening, helped found the Geneva chapter of the YMCA and three years later was active in creating its international organization.3

As Dunant’s humanitarian life blossomed, he simultaneously devoted energy to his professional life. Dunant started an apprenticeship in banking and ultimately took a finance job with the Geneva-based company Compagnie des Colonies suisses de Sétif.4 In 1853 the company sent him on assignment to Algeria. The North African people and culture transfixed Dunant. Despite his deep Christian roots, he studied both the Islamic religion and Arabic.5 Furthermore, after successfully completing his assignment, he committed to continuing work in Algeria, creating his own company Societe Anonyme des Moulins de Mons-Djemila to grow crops and build mills in the country. He capitalized 100,000,000 francs and acquired land rights, but the Algerian colonial authorities blocked his access to water.6,7

After exhausting his contacts in Paris and still lacking water rights, Dunant decided to take his case directly to Emperor Napoleon III (the son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother). To be sure, it was a bold move, made even bolder by the fact Napoleon III was not in France. He was fighting a war in Italy.8

Undaunted, Dunant set off to track down the emperor in Solferino, where French soldiers joined the fight for Italian independence from Austria. Dunant never found Napoleon.

On June 24, near Solferino, fighting broke out in a battle that produced so many casualties it would be compared to Waterloo and Leipzig. French and Piedmontese forces totaling over 100,000 troops engaged an Austrian force of equal size. The fighting was particularly gruesome. The use of swords and bayonets left disemboweled bodies on the battlefield; others were torn apart from bullets and cannonballs, and skulls lay crushed from rifle butts.9

The night of the 24th, Dunant arrived by carriage in Castiglione, a small town near the Solferino battle. Thousands of wounded soldiers lined the streets and filled the town square. Dazed by the horrors, he descended his carriage and set off by foot up the road to the church Chiesa Maggiore. Dunant entered the church and was greeted by the screams of wounded soldiers and the fetid smell of excretion and infection.10

Dunant had no medical training but went to work helping the soldiers. He cleaned wounds and made dressings. Thirst was also a major problem for the wounded. Dunant wrote:

There, is an unfortunate man a part of whose face, the nose, lips and chin have been cut away by the stroke of a sword. Incapable of speech, half blind, he makes signs with his hands, and by that heartrending pantomime, accompanied by guttural sounds, draws attention to himself. I give him a drink by dropping gently on his blood-covered face a little pure water.11

Inside the church, Dunant found French soldiers as well as Austrian soldiers. Some of the latter, suspicious of the care they received, tore bandages from their wounds. Dunant, however, resolutely stuck to a moral principle of treating all the wounded equally, no matter what their nationality.

During the days following the battle, Dunant also recruited local women to help provide care. He noticed that they followed his example of treating all soldiers no matter their origin; and while they worked, he repeatedly heard them say tutti fratelli, meaning all brothers.12

Dunant eventually returned to Paris; and after unsuccessfully lobbying authorities to help with his water problem, he traveled home to Geneva. The entire time his thoughts kept returning to Solferino. He reached an emotional and inspirational tipping point that resulted in his writing a memoir Un Souvenir de Solferino (A Memory of Solferino).

Battle of Solferino, June 24, 1859. Adolphe Yvon. 1861. Collections du château de Versailles.

Dunant’s writing vividly captured the battle of Solferino and its aftermath, as well as his efforts to provide medical care. The descriptions range from journalistic: “The line of battle is ten miles long. . . . On all sides bugles are playing the charges and the drums are sounding,”13 to literary:

“A little further on lies a dying Zouave who is weeping bitter tears, and we console him as if he were a little child. The preceding fatigue, the lack of food and repose, the intensity of the pain, the fear of dying without help, excites even in these brave soldiers a nervous sensibility which betrays itself by sobs.”14

The book received praise for its quality of writing and quality of content. Dunant’s genius, however, was in the form. After describing the battle and the aftermath, Dunant wrote a prescription for how to better serve the wounded during war. He called for a congress to draft and ratify a set of principles allowing aid societies, under the direction of committees, to provide relief during war. Dunant wrote:

“In order to establish these committees at the head of the societies, all that is necessary is a little good-will on the part of some honorable and persevering persons. The committees, animated by an international spirit of charity, would create corps of nurses in a latent state, a sort of staff. The committees of the different nations, although independent of one another, will know how to understand and correspond with each other, to convene in congress and, in event of war, to act for the good of all.”15

In 1863, having read Dunant’s book, Gustave Moynier, the president of the Public Welfare Association of Geneva, contacted Dunant about putting his humanitarian relief program into action. They created a five-person committee that organized a four-day conference held in Geneva.16 Delegates from sixteen nations attended the International Conference, and on October 29 they passed ten resolutions and three wishes. The resolutions called for establishing medical relief societies, holding additional conferences, and creating the symbol for all medical personnel to wear: a red cross on a white background, the inverse of the Swiss flag. The wishes reflected Dunant’s desire for all medical personnel to be considered neutral in war. With the passing of the resolutions and wishes on October 29, the Red Cross was born.17 The official name International Committee for Relief of Wounded Soldiers was changed in 1876 to the International Committee of the Red Cross.

After fulfilling his vision for creating an international relief organization, Henry Dunant’s life spun into a sad denouement. During the years of his humanitarian work, Dunant neglected his Algerian business, which folded. Then in 1867, the bank Crédit Genevois declared bankruptcy. Dunant sat on the board and personally declared bankruptcy, a move that resulted in his formally being charged for deceptive practices.18 With his reputation tarnished, Dunant was forced to resign as secretary of the International Committee, his humanitarian vision born on the bloody battlefields of Solferino.19

During this time, Dunant moved to Paris. With his finances depleted after years of traveling at his own expense for humanitarian work, he used chalk to whiten his shirt and ink to blacken his coat; and at times, he ate bread crusts and slept outdoors. For several years, he tried to continue working humanitarian causes, but then in 1875 Henry Dunant, the man who gave the world the International Committee of the Red Cross, disappeared.20

For fifteen years, Dunant’s whereabouts were unknown and Geneva newspapers published he had died. However, in 1890 in the small Swiss village Heiden, schoolchildren told their teacher about a man in a black cap and white beard that engaged the students. The teacher Wilhelm Sonderegger investigated and discovered it was Henry Dunant. Sonderegger wrote the International Conference of the Red Cross in Rome so they could inform the delegates.21 The news did not evoke a strong response, but three years later journalist Georg Baumberger visited Heiden and interviewed Dunant, who lived in a hospice. His subsequent article delineating both Dunant’s poverty and massive contribution to society touched people. The article was widely circulated, earning Dunant a revival in popularity.22

With the fire of Dunant’s renown reignited, the Nobel Committee in Norway awarded Henry Dunant the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, along with Frédéric Passy, organizer of the first Universal Peace Congress. The Committee congratulated Dunant with the following statement:

There is no man who more deserves this honor, for it was you, 40 years ago, who set on foot the international organization for the relief of the wounded on the battlefield. Without you, the Red Cross, the supreme humanitarian achievement of the 19th century would probably have never been undertaken.23

Despite his resurgence into the public spotlight, Henry Dunant never left the hospice in Heiden nor did he spend any of his prize money. He died in October, 1910. Having abandoned the religion that had been the driving force early in his life, he called for no funeral and to be carried to his grave “like a dog.”24

Today the International Committee for the Red Cross has 18,000 staff in over ninety countries and is the largest humanitarian organization in the world.25

Endnotes

- Henry Dunant – Biographical. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2019. Wed. 11 Dec 2019. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1901/dunant/biographical/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Pierre Boissier. Henry Dunant. Henry Dunant Institute, 1974.

- Warner, Daniel. “Henry Dunant’s Imagined Community: Humanitarianism and the Tragic.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political. Vol. 38, no. 1, 2013, pp. 10-11.

- “Jean Henri Dunant.” New World Encyclopedia. 1 May 2018. www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Jean_Henri_Dunant&oldid=1011223. Accessed January 13, 2020.

- Pierre Boissier, Henry Dunant. Henry Dunant Institute, 1974.

- Ibid.

- Henry Dunant – Biographical. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2019. Wed. 11 Dec 2019. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1901/dunant/biographical/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Ibid.

- Dunant, Henri, translated by Wright, Mrs. David H. The Origin of the Red Cross, “Un Souvenir de Solferino.” The John C. Winston Co. 1911, pp. 2-5.

- Pierre Boissier. Henry Dunant. Henry Dunant Institute, 1974.

- Dunant, Henri, translated by Wright, Mrs. David H. The Origin of the Red Cross, “Un Souvenir de Solferino.” The John C. Winston Co. 1911, p. 31.

- Ibid. pp. 39-40.

- Ibid. p. 5.

- Ibid. pp. 37.

- Ibid. p. 90.

- Pierre Boissier. Henry Dunant. Henry Dunant Institute, 1974.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Henry Dunant – Biographical. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2019. Wed. 11 Dec 2019. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1901/dunant/biographical/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Harvey, Holman. “Evangelist of Mercy.” Rotarian, September 1944: p. 52.

- Pierre Boissier. Henry Dunant. Henry Dunant Institute, 1974.

- “Jean Henri Dunant.” New World Encyclopedia. 1 May 2018. www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Jean_Henri_Dunant&oldid=1011223. Accessed January 13, 2020.

- Henry Dunant – Biographical. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2019. Wed. 11 Dec 2019. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1901/dunant/biographical/. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- “The ICRC worldwide,” ICRC, https://www.icrc.org/en/where-we-work. Accessed January 13, 2020.

STEPHEN KOSNAR is a freelance writer interested in healthcare topics. He has written for the Medical Review of North Carolina as well as the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He currently lives in Lima, Peru, with his wife (a physician) and three children.

Winner of the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply