Frank Gonzalez-Crussi

Chicago, Illinois, United States

The feverish imagination of poets has ever eulogized the beauty of feminine hair. The beloved’s hair has been represented as golden threads, sunrays, fragrant flowers, or astrakhan fleece (wool famous for its tight, shiny loops). Richard Lovelace spoke of it as “sunlight wound up in ribbands.”1 To Charles Baudelaire, his mistress’ head of hair was “an aromatic forest” and “a sea of ebony”; her tresses, “the billows” that carried him away.2 Plenty of other tropes─delicate or crass, depending on the author’s sensibility─occurred to poets. From nets that bind men in servitude to celestial threads drawn out from heaven: elegists imagined all this where more pedestrian minds might have descried a shock of hair with hanging rattails. But the fanciful similes originate from the fact that a woman’s hair is endowed of a powerful erotic charge: an invisible force much like that which Thales of Miletus discovered thousands of years ago by rubbing a piece of amber, only many times more powerful. For let feminine hair so much as brush, ever so slightly, the surface of a sensitive man’s skin and a clamorous call will arise in the male, urging him to attend to the perpetuation of the species.

To be fair, much of what is said about the feminine head of hair could be applied just as well to the male. Especially today, when the boundary lines between the genders are less trenchant than before. In Hemingway’s posthumous novel, The Garden of Eden, a short-haired woman adopts the traditional male role in a torrid affair with a man who wears his hair long. Hemingway sees to it that his personages invert the roles considered traditional for each of the sexes. An intriguing scenario coming from Hemingway, celebrated epitome of machismo. This lion-hunter, death-defying daredevil, war pilot, boxer, and fervid aficionado of bullfights, comes to tell us that the lines of demarcation between the sexes are imprecise and blurry, and in the last analysis illusory, for there is no clear-cut, unbridgeable abyss between masculinity and femininity. And he chooses as the ensign and blazon of this vagueness the hair-length of his novelistic couple: long in the male, short in the female.

Indeed, much of what has been said about feminine hair in history─source of pride, seduction tool, sign of vanity, token of identity─applies equally well to the male head of hair. The ancient Greeks paid more attention to capillary comeliness in men than in women. Homer, at least, reveres the crinal splendor of his heroes, yet disregards the headdress of his heroines, even the goddesses. Thus, he calls Aphrodite “golden”; Hera, “large-eyed”; Thetis, “silver-footed.” Only when speaking of Zeus he punctually mentions how “the divine locks waved from his immortal head.”3

Concerning men, Homer praised the hair of Greeks and Trojans with equal ebullience. When Athena appears on the earth, she stops Achilles “by his golden hair” (I, 197). And when this hero ties the cadaver of Hector to his chariot and thus tied drags him on the ground, Homer can think of no better way to enhance the pathetism of this jarring scene than to say that as Hector was being dragged, “his dark hair flowed outspread, and all in the dust lay the head that had once been so beautiful,”4 while his mother, horrified, watched the terrible spectacle howling in pain.

In the Odyssey, Athena rejuvenates a senior Ulysses, gives him new garments, restitutes his former youthful complexion, and, of course, his pitch-black hair (XVI, 176). And when Athena wishes to make a greying Ulysses more handsome in the eyes of Nausicaa, she makes him taller, stronger, and more dashing. But what mostly captures the goddess’ attention is the beautification of the hero’s head of hair, which she turns thicker and waving downward “in curls that are like hyacinths in bloom” (VI, 230, cf).

Truly, men have been no less vain than women in this regard. Only here “the sin carries its own penance,” for male hair is deciduous: one-fifth of all men will show some loss of hair, (total, on occasion), even in their twenties. The prevalence rises strikingly between the ages of thirty and forty, and it is very rare to find men in their eighties unaffected by at least some degree of visible baldness. Alas, hairs depart never to come back spontaneously, “unless it be in the soup,” wrote a humorist, “and there I prefer vermicelli.”5 Strictly speaking, male-pattern baldness is not a disease, since the subject’s physiology is normal. Yet hair loss causes severe anxiety, depression, and psychosocial distress, especially among younger men,6 who feel they have become less attractive to the opposite sex. Hence the desperate efforts throughout history to conceal baldness with wigs, caps, hats, and all species of headgear.

Two British physicians remarked that artists seldom represented baldness in all its refulgent splendor.7 Sitters covered their polls even when expected to display them bare. In Jean Huber’s (1721-1786) painting of Voltaire rising from bed in the morning and awkwardly putting on his trousers, his braincase is still enclosed in a nightcap. “He made me look ridiculous from one end of Europe to the other,” bitterly complained the sage of Ferney upon seeing one of the caricatures derived from the painting (Fig.1).

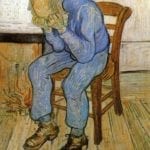

The above-mentioned authors suggested that a gloomy work of Van Gogh, Old Man in Sorrow, may be taken as emblematic of the profound depression sometimes associated with hair loss. A man sits on a chair, elbows on his thighs, head lowered and fists against his face. It is impossible to see his face; instead, we see his ungarnished pate (Fig. 2). Van Gogh painted this just before committing suicide. Tellingly, On the threshold of eternity is another name for this powerful, melancholy masterpiece.

When hair loss was irremediable, men found some solace reading a playful text by Synesius (c. 373-c.414), bishop of Ptolemaic in Cyrene (today’s Libya), titled In Praise of Baldness. Homer and all those writers who eulogized hair, says Synesius, would have produced work worthier of their abilities, had they employed these in praising baldness. For a scalp may be bare, but the brain underneath seethes with luxuriant intelligence. Hunters know that the cleverest dogs are those with smooth ears and bellies, whereas the most inept are those with lots of hair. In Plato’s allegory, the human soul travels in a chariot drawn by a pair of horses: one horse is docile to the soul’s commands; the other wild and rebellious. Why is this animal deaf to good counsel? Because his ears are blocked up with overabundant hair. Note that the divinest part of our bodies is the eyes, which are also the smoothest; the worst misfortune is to have hair growing into the eyes.

Walk into a museum that contains the effigies of wise men and rulers of peoples. You will think that you have come into a theater of bald men. Young men have an abundant crop of hair; youth is also the time of thoughtlessness and unruly passions. But when reason and intelligence set in, and take residence inside the head, the time has come to impugn the unreasonableness of hair. It is true that there are some old men with hair, for not everyone evolves toward human perfection. The seed that is cast on the earth has great power: the cereal exists potentially inside of it. When it comes out, it sheds all unimportant matter, for perfection needs no beautification. As nature removes the ears and the husks and the flowers before the fruits, so it ceases to decorate the head, from which it removes the hair, before true wisdom ripens to perfection.

Contemporary men have a number of alternatives to an ungarnished skull-top. But those unable or unwilling to afford the considerable expense of time and money of remedial procedures would do well to read Synesius. They will be pleased to find out that baldness is wisdom; that sheep are among the stupidest animals because they grow abundant hair; and that humans are the crown of Creation, which is why they were given a glabrous skin.

References

- In Richard Lovelace’s poem “Song to Amarantha, that she should Dishevel her hair.”

- Charles Baudelaire, in his poem “Her Hair” (La Chevelure) in Les FLeurs du Mal. Seven different English translations may be seen here : https://fleursdumal.org/poem/203

- Homer : Iliad Book I, 529. The translation by A. T. Murray reads: “the ambrosial locks…” Cambridge, Mass Harvard University Press. Loeb Classical Library. Last printing 1988. Vol. 1. p 43..

- Ibid. Book XXII 400-407, Vol. II, p. 485.

- E. Grosclaude: La Calvitie. Monologue en Prose. 2nd edition. Paris. Ollendorff. 1888.

- C.J. Girman et al. : “Effects of self-perceived hair loss in a community sample of men.” Dermatology 197: 223-229, 1998.

- J.K. Aronson and M. Ramachandran: “The diagnosis of art: Van Gogh and male pattern baldness.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 102: 32-33, 2009.

FRANK GONZALEZ-CRUSSI, MD, now retired, is Emeritus Professor of Pathology of Northwestern University. He has written numerous essays on Medical Humanities. For an overview of his work, see his Wikipedia.

Leave a Reply