Julius Bonello

Ayesha Hasan

Peoria, Illinois, United States

A belief held by the common people is that it is good to be royalty, a sentiment supported by descriptions in novels and depictions in movies. The best food, the finest clothes, and the most extravagant and opulent dwelling in the kingdom belonged to the king to use at his whim. Even his medical needs were taken care of by the best doctors and “surgeons” in the land. However, medical therapy was only as good as the state of medical knowledge at that time. In the Middle Ages, medical knowledge and treatment incorporated bleeding, prayers, purgatives, and enemas. Physicians avoided surgery because infection and death plagued surgical outcomes. Only a lower class of doctors, called barber-surgeons, performed surgery. Louis the XIV, known as the Sun King, suffered from a minor illness that would require medical attention. Unfortunately, the state of medical affairs in the late seventeenth century was stagnant and deplorable. Luckily a very capable barber-surgeon would rise to the challenge to cure the king and change forever the history of surgery and medicine.

King Louis-Dieudonné XIV, born September 5, 1638, was the longest ruling king in European history. On May 14, 1643, his father King Louis XIII died from tuberculosis and gastrointestinal disease. At the tender age of four, King Louis XIV inherited the crown of France in the midst of the deadly Thirty Years War. His mother, Queen Anne the regent, and the Chief Minister Cardinal Mazarin dominated political and financial policy. Believing in the divine right of kings, they worked to centralize the government and consolidate the king’s power. This disenfranchised the nobles, and with growing dissent from the parliament, civil war broke out in 1648. Fleeing Paris to save their lives, Queen Anne and her ten-year-old son, the king, were subject to poverty, starvation, and eventually house arrest. These events weighed heavily on young Louis’s mind and gave him a lifelong distrust of Paris and its surroundings.

After the death of Cardinal Mazarin in 1661, a twenty-three-year-old Louis the XIV surprised his parliament and decided to rule France without a chief minister. To mollify the nobility who had opposed him as a child, he invited them to share in his emerging opulent and lavish life style, but he had to leave Paris to do so. About twenty-five miles southwest of Paris, Louis’s father had built a hunting lodge in the small village of Versailles. Being a Renaissance man and a true student of art, music, and architecture, Louis XIV began renovations of the lodge on a grand scale. Hiring the top architects and painters, he transformed the hunting lodge into a palatial home for the royal family. Eventually he moved the government’s headquarters to the redesigned Versailles in 1678.

As the leader of the most powerful country in Europe, the ambitious king sought to expand his domain. In his later years he launched five wars, three major and two minor, with the belief that the European territories were rightfully his through his lineage. Despite having the greatest army and navy in Europe, France did poorly and made no real gains in territory. It left the country depleted and its people hungry, destitute, and distrustful of the monarchy.

Amidst these wars, the devoutly Catholic Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, rescinding the French Protestants’ freedom to worship and assemble. All French children were to be baptized and raised Catholic. This caused almost one million Protestants to leave France and immigrate to other countries, divesting the country of some of its finest artisans.

Louis’s health

Louis XIV’s physical appearance was not as robust as depicted by court-appointed artists. Standing 5’6” with a face scarred by childhood smallpox, the word majestic is difficult to apply. As an adolescent, he suffered from a variety of skin diseases, bouts of diarrhea, and frequent headaches. As an adult he endured measles, attacks of gout, rheumatism, tumors, and vapours—an archaic term for a host of both mental and physical ailments. While undergoing extraction of his left upper teeth a part of his maxilla was accidentally removed, which made chewing difficult and caused bits of food to come out of his nose while eating.

An entry in the Journal de la Sante du Roi by a royal physician on January 15, 1686 reported, “His majesty today complained of a small tumor towards the perineum, approximately two finger-breaths from the anus.” Decidedly, the king would need a surgeon. A plea for surgeons produced a cadre of nine out-of-date physicians, one whose earlier treatment helped dispatch Louis’s first wife by overprescribed purgatives and excessive bloodletting for an abscess under her arm.

Even though the royals proclaimed to have the finest doctors in the land, the outcomes left much to be desired. During the 1700’s, the French medical community was in disarray. Despite being one of the oldest schools of medicine in the world, the University of Paris medical school’s curriculum was stagnant. Its creed: “Medicine was invented by Apollo, brought to perfection by Hippocrates [460–370 BC] . . . and Galen [AD 120–210] had carried this perfection as far as human reason could reach.” Students were told to learn the masters and ignore any “discoveries” in a science that had reached “perfection” more than twelve centuries before.

Surgery was in no better shape. Barbers were given permission to perform surgery in the eleventh century. Surgeons belonged to a guild that included grocers, bath-keepers, and public executioners. Two distinctive ranks of surgeon emerged, one of barber-surgeons and the other of surgeon-barbers. The surgeon-barber took an apprenticeship of two years. In contrast, the barber-surgeon, with more education and under the patronage of St. Come, enrolled in a six-year course with a possible extra seven years in a junior partnership, equivalent to a surgical residency today. Even with this education, they were always subservient to the College of Physicians. This inferior position was about to change.

The physicians to Louis XIV immediately ordered enemas (the king enjoyed over 2000 during his lifetime) and a poultice (a wet mixture covered with a cloth) of peas, beans, rye, barley, and flaxseed all boiled in water and vinegar. Other measures included emetics, application of leeches, and bleeding. Because of the severe pain, the king stayed in bed for a week. The skin became inflamed and soon an abscess started to form, whereby the physicians then placed a feather broom coated with a suppurative and applied a plaster of Manus Dei (Hand of God) to draw out the infection.

On February 5, the abscess had fully formed, and a surgeon proposed lancing it. Of course, the faculty challenged this suggestion. A compromise was reached, and the abscess was opened. The physicians again applied suppuratives and potassium hydroxide. The abscess needed re-incised on February 20 and again on the 23rd. In the meantime, gout occurred in the king’s right foot, keeping him immobilized and bedridden. The physicians applied another poultice of absinthe seeds, petals of rose of Provins, myrrh leaves, and pomegranate seeds boiled in red wine.

An apothecary now suggested a new miracle medicine: water plantain, yellow wax, liquid mint, and balsam of Peru mixed in a large volume of concentrated turpentine. As a result, the abscess increased both in size and pain, and, congruently Louis suffered an attack of gout in his other foot. The physicians applied a mercury oxide caustic to the abscess for a week. On March 8, the abscess became extremely painful and the faculty attacked it again with potassium hydroxide, lunar caustic, mini incisions, and painful soundings of the sinus. The lesion was now four fingers in length. On March 17, after two more weeks of this treatment plus the application of leeches, the cavity was healed. The king was healed. The physicians had won . . . almost.

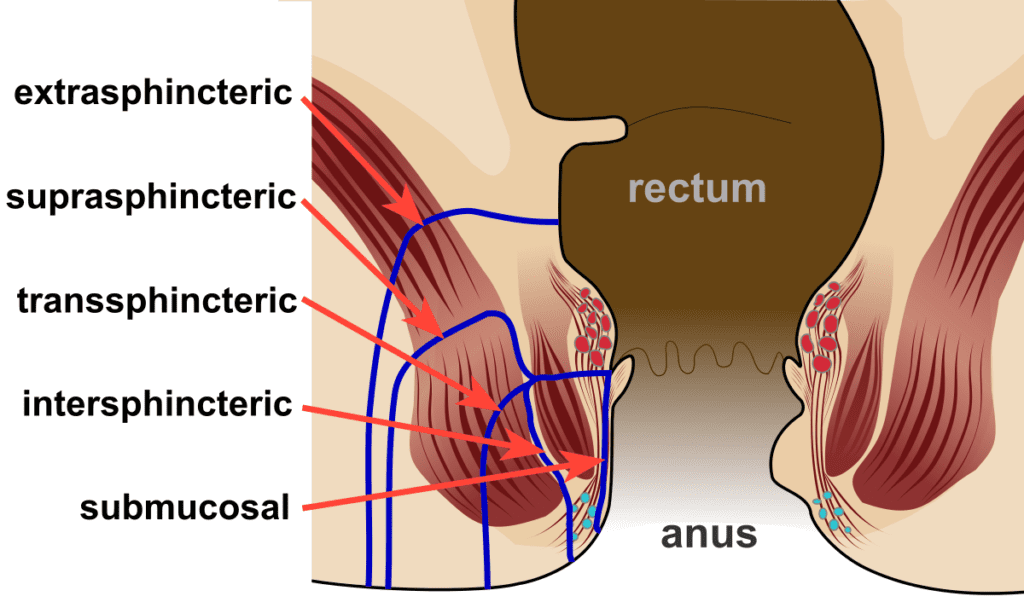

On May 21, 1686 the faculty of physicians officially recognized that the king had developed an anal fistula. The medical community had recognized anal fistulas since the days of Hippocrates. During the Middle Ages, fistulas were operated on by a syringotome, a sharp, almost circular knife developed by Galen in the second century. During the sixteenth century, the instrument was modified and perfected. The method had fallen out of favor because of the pain involved, but revived in 1654 based on 600 mostly successful operations by Pietro Marchetti. By the time Louis XIV had developed his fistula, the method had gained in popularity. Enter Charles-Français Felix de Tassy, a barber-surgeon. Felix examined the king and corroborated the diagnosis of a fistula. He suggested to the king that some study of both anatomy and technique would be required to perfect a procedure that would be successful.

Felix then spent time both in the anatomy theater and in the operating room. Arrangements were made in a Paris hospital for Felix to perfect his operation upon impoverished patients and prisoners. Approximately seventy-five operations were performed with rumors that several subjects did not survive. In true Machiavellian fashion, the ends justified the means. His experience led him to devise a new narrower instrument and a retractor to be used during the operation.

In the king’s bedchamber at the palace of Versailles at 7 AM on November 18, 1686, Felix performed the operation with no anesthesia. It was recorded that the king never uttered a sound of pain, and an hour later he submitted to bloodletting by his physicians.

A month later on December 6 and December 8, Felix had to perform further surgeries to avoid complications. In a painful six-hour operation on December 10, Felix performed his final procedure. In early January 1687, Louis XIV’s fistula had healed. His two-month ordeal was over.

The king was quite pleased with the results of the operation and bestowed upon Felix a reward of 15,000 Louis d’Or (approximately $1.8 million today) and a country estate. He was knighted and was to receive 1,200 Louis d’Or a year (approximately $140,000). This ennoblement of Felix placed the surgeon on par with the physicians at court. A new surgical amphitheater was built at St. Come. A surgical revolution had begun.

Under King Louis XV, the right of surgeons to teach was upheld, and in 1731 the surgeons received permission to organize what would become the Royal Academy of Surgery, the leading surgical forum in Europe. King Louis XV eliminated the union of surgeons and barbers, terminating the occupation of barber-surgeon in 1743. Under the guidance of King Louis XVI in 1789, the year of the French Revolution, all distinctions between medicine and surgery were eliminated and surgery was taught in medical school for the first time.

I have been privileged to teach surgery to over 2,000 medical students over the past 43 years through the University of Illinois. For this privilege, I can thank Felix and his success with fistulas. As a colon and rectal surgeon, it makes sense to me that the pivotal point in surgical education revolved around a rectal procedure . . . It is rather fundament-al.

References

- Bodemer, CW; France the Fundament and the Rise of Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 1983;26;743-750.

- Hourly History, 2017, King Louis XIV: A Life From Beginning to End. Monee, IL, Hourly History.

- Lewis, WH; 1954, The Splendid Century: Life in the France of Louis XIV, New York, NY, Morrow & Company.

- Jorum, Ellen; Sun King’s Anal Fistula, Tidsskriftet, Aug, 23, 2016; Issue 14, 1244-1247.

- Fr.wikipedia.org. (2019). Charles-François Félix. [online] Available at: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Fran%C3%A7ois_F%C3%A9lix [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

- En.wikipedia.org. (2019). Anal fistula. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anal_fistula [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

JULIUS P. BONELLO, MD, is originally from Minnesota and received his undergraduate degree in 1970 from the College of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. He completed a Fellowship in Colon and Rectal Surgery at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1980. Dr. Bonello was on the surgical faculty at the Carle Clinic, Urbana-Champaign from 1980 to 1996. He was Chair of the Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery and Program Director for the Colon and Rectal Surgery Fellowship from 1988 to 1992. He is the author of four chapters and 30+ articles, most recently historical articles on interesting cases and people in medicine published in History Magazine. Dr. Bonello has taught students and residents for the last 45 years at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. He now holds the title of Professor Emeritus of Clinical Surgery. He has eight children and lives in Peoria, IL with his wife of 33 years.

S. AYESHA HASAN, MD, is from Chicago, IL. She graduated from Case Western Reserve University with a degree in Economics, and received her Medical degree from the University of Illinois College of Medicine. Currently, she is an Internal Medicine Resident at OSF Hospital, University of Illinois College of Medicine. Her research interests include gastro-intestinal disease and health care analytics.