Andrew Bamji

Rye, East Sussex, UK

Modern warfare, and in particular the use of artillery employed against entrenched troops in the First World War, resulted in a large number of facial wounds in all armies. Surgeons were unprepared. Advances in the management of infection and surgical shock resulted in better survival from wounds that would previously have proved fatal, so many more reached facilities where surgery might be undertaken.

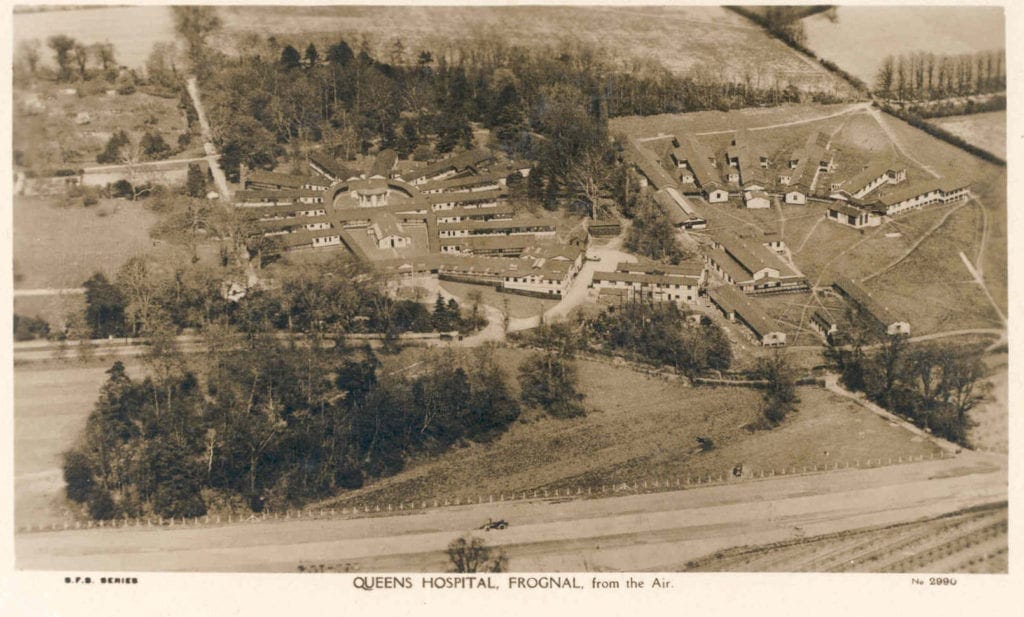

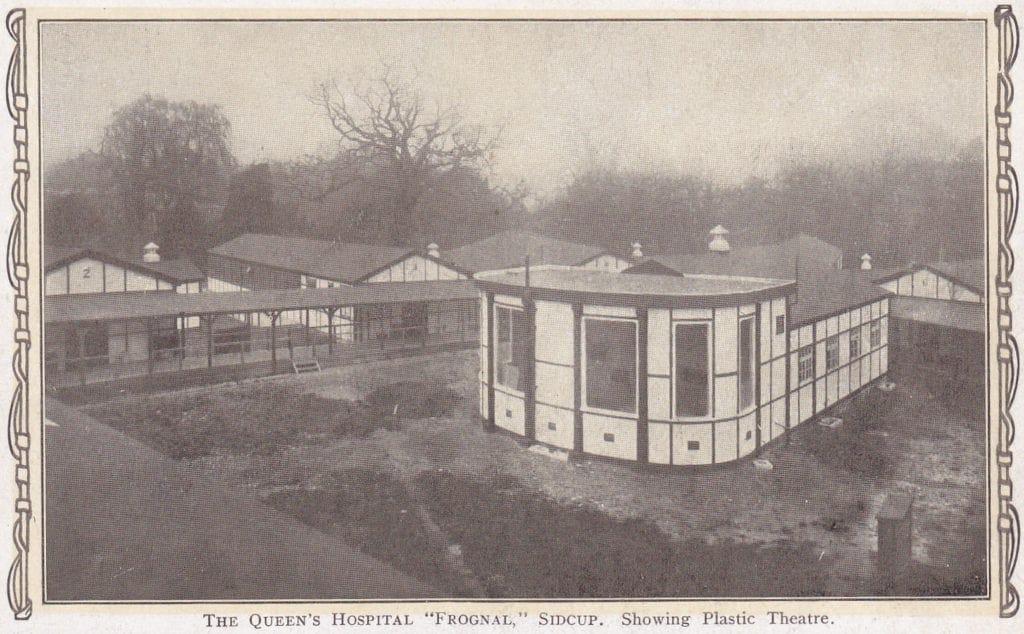

In France and Germany facial services were divided between a number of hospitals. Thus no surgeon dealt with many patients; their results were poor and there was not the volume to experiment with new techniques. By contrast in England a single hospital was established in Sidcup, Kent, following the initial setting-up of a dedicated unit within the main garrison hospital, the Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot. This unit was the brainchild of Harold Gillies, whose experience in France, where he was attached to the 83rd General Hospital in Boulogne and tasked to oversee the work of a French-American dentist, Charles-Auguste Valadier, led him to realize that facial injuries would be common, and that concentrating patients and surgeons in one place would advance surgical practice.

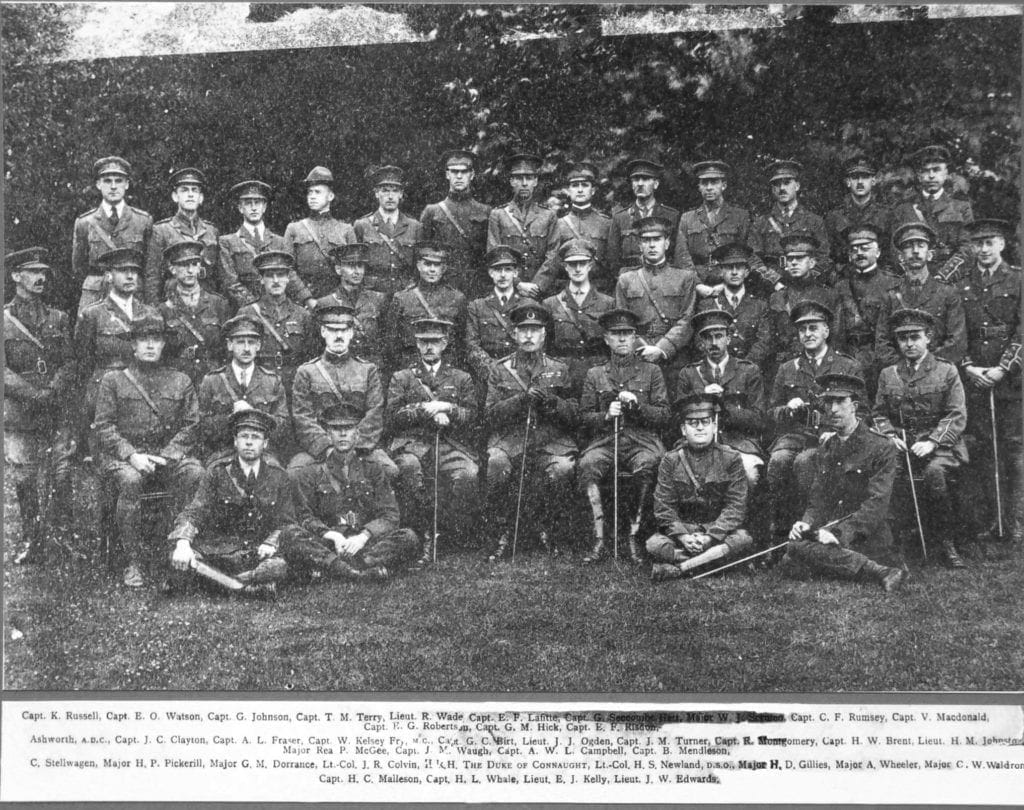

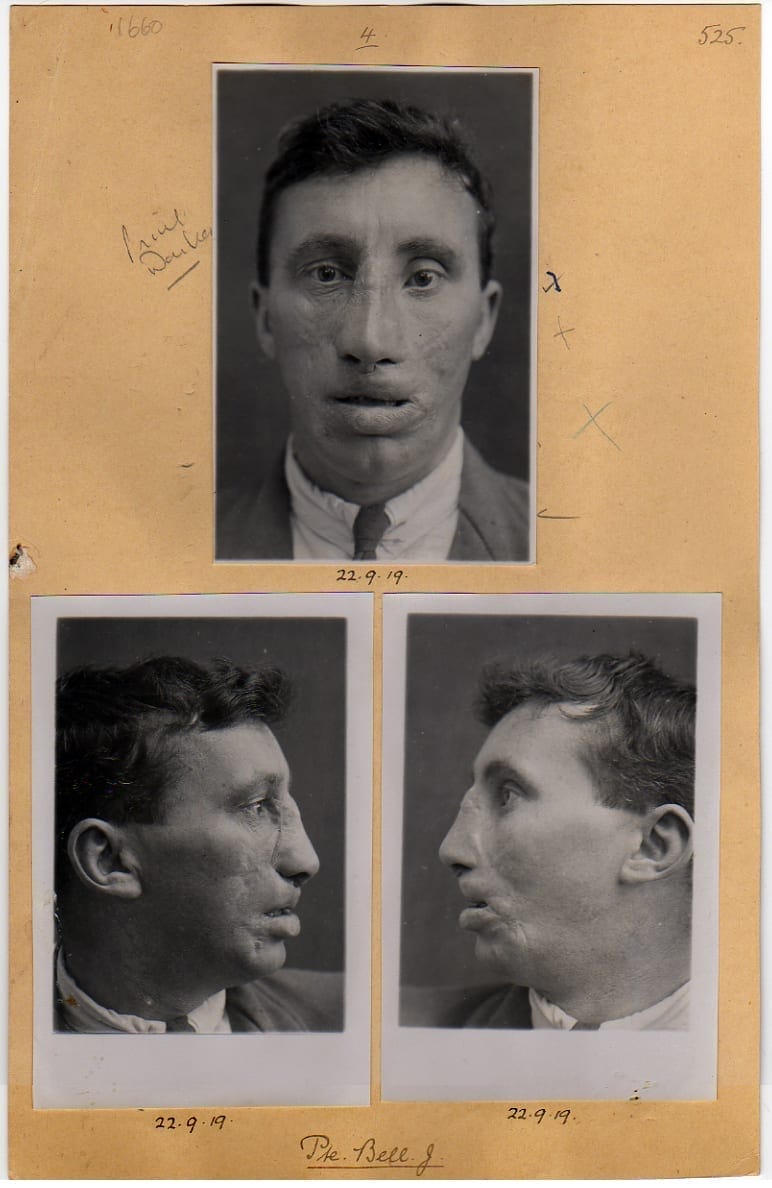

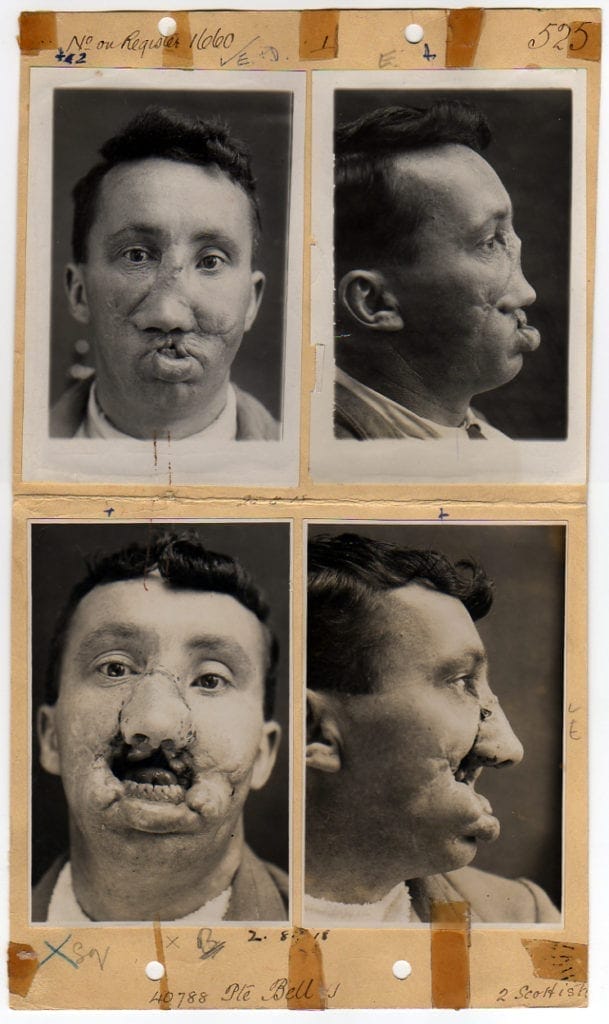

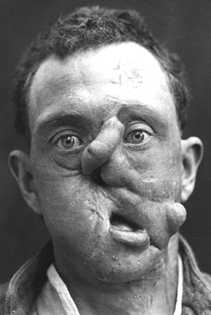

Gillies opened his facial ward at Aldershot at the beginning of 1916. There was insufficient capacity. By the end of the year he had persuaded the army’s chief surgeon that a full hospital was required. It was funded by donations, and advertisements were placed in local newspapers across the country in January 1917 to solicit these. The Queen’s Hospital was opened in August 1917 and operated as a facial hospital until 1925; surgeons were divided into sections by nationality (British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand) with, by 1918, a number of attached American surgeons (figures 1-3). Convalescent beds scattered in the locality gave a bed complement of over 1000, and the main hospital had pathology, radiology, dental technicians, and rehabilitation facilities.

The concentration of both patients (over 5000 passed through Sidcup) and surgeons resulted in substantial improvements in the care and outcomes of men with facial injuries.

At the outset of the First World War and the appearance of the first facial casualties, it appears to have been presumed that facial disfigurement would result in misery and isolation. Newspaper articles printed in January 1917 advertising the planning of the Queen’s Hospital (with the purpose of soliciting donations) underlined this likelihood. The autobiography of Catherine Black contains a moving account of a young soldier who obtained a mirror, decided that his appearance was a disability, and wrote to his fiancée to break off their engagement, using as an excuse the false statement that he had met a girl in France.1 This account is widely quoted in present-day discussions of facial trauma and its wartime impact. Likewise the testimony of a journalist working as an orderly at the 3rd London General Hospital, Ward Muir, reinforced the impression that men would suffer because of the attitude of others on seeing their injury.2

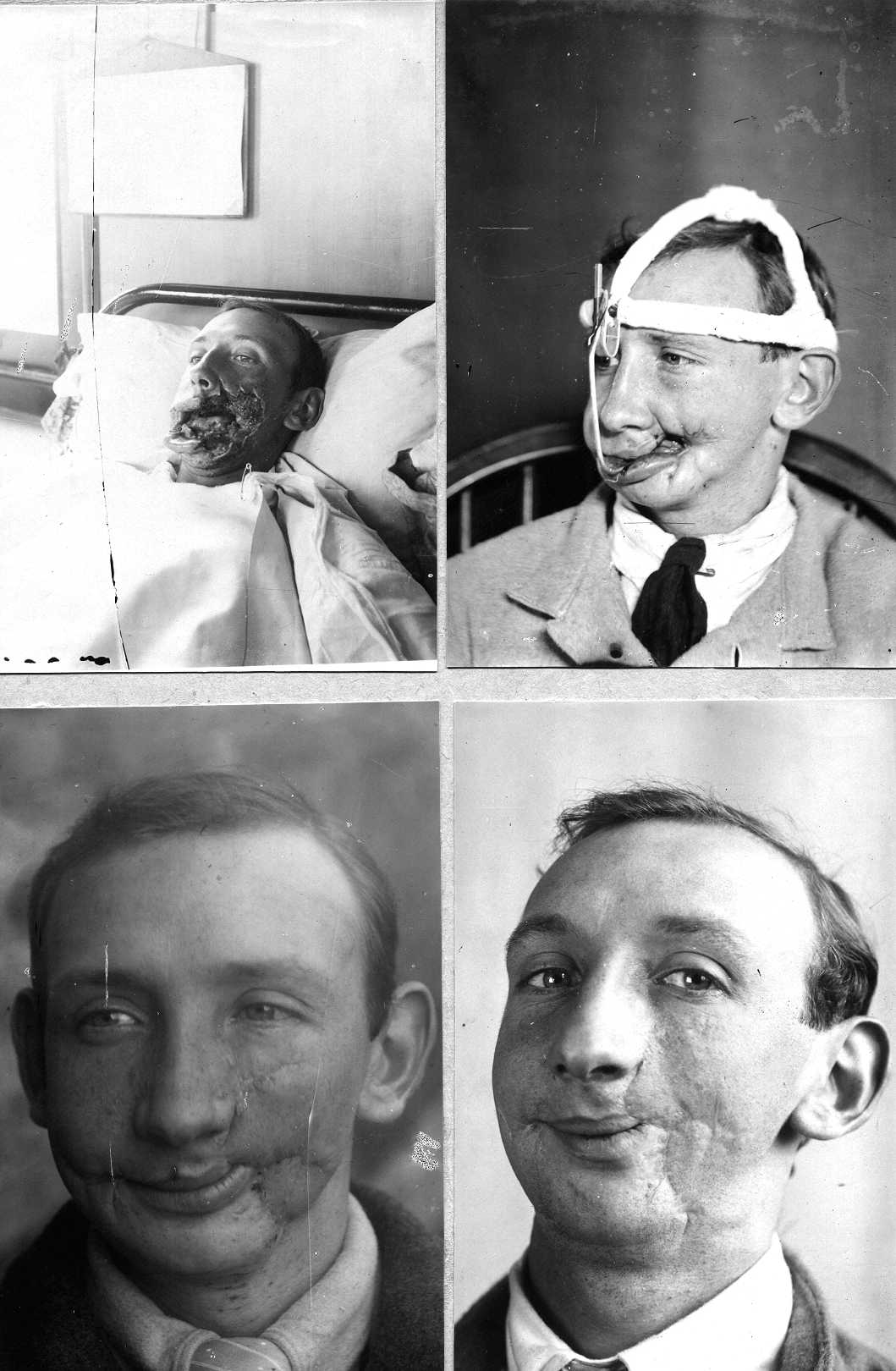

It has long been supposed that Black’s experience of facial injury nursing was extensive and her report representative. But Black encountered Harold Gillies at Aldershot after he had returned from France in January 1916 and was herself posted to France in August. During the seven months that she worked with Gillies he was in the early stages of learning to manage serious facial injury; the majority of his early patients at Aldershot were, effectively, experimental subjects. He applied the methods outlined in contemporary texts and discovered they did not work. As Black never visited Sidcup she could not have appreciated the vast improvements that followed the concentration of resources and patients. Not only were reconstructions demonstrably good, but the need for psychological support was fully realized. Men were given duplicates of the serial photographs taken for the case files which provided clear evidence of how much worse their appearance would have been without surgery. The atmosphere within the hospital was a positive one.

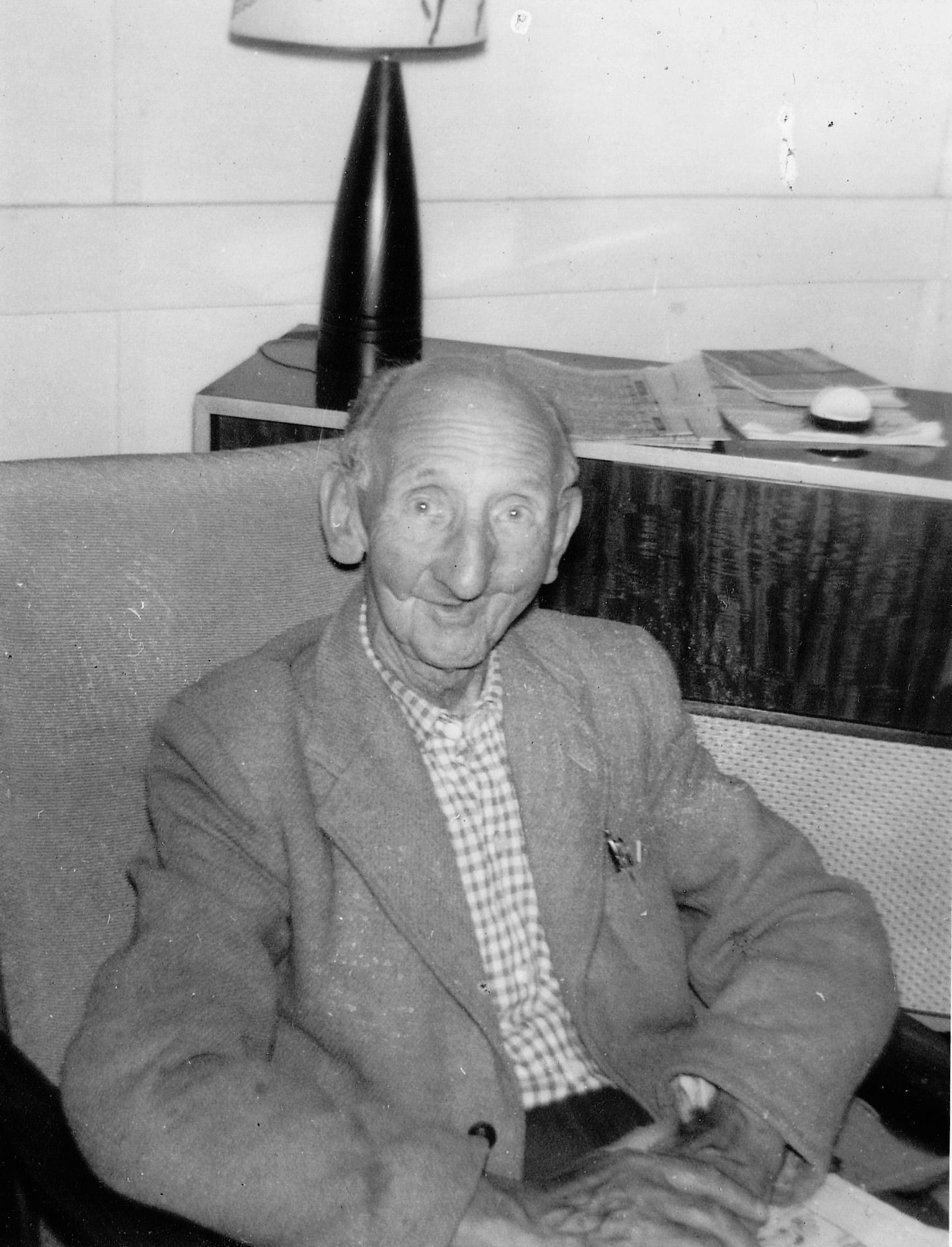

Over 2500 case files of the Queen’s Hospital survived. I was able to recover them and constructed an online database as part of a website describing the work at Sidcup.3 Over twenty-five years I received many enquiries through the website about Sidcup patients from relatives and researchers, and in return for supplying details I asked for information on the post-war lives of the subjects. The majority—and I have now received over 100 reports—indicate that most men did not lead cloistered and miserable lives, but full and happy ones. They married, had families, worked hard, and were greatly respected and loved by their relatives. There were a few exceptions; some found their families or fiancées unable to accept the disfigurement, but even then they were able to overcome most obstacles. The natural attitude of the men is embodied by Joseph Pickard, whose wartime life was recorded in oral interview.4 The daughter of Walter Ashworth wrote how her father’s sweetheart threw him over, only for her best friend to take up with him, and they had a long and happy married life (figures 4 and 5).5

In some cases where there were obvious signs of what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder, the psychological disturbance was not the result of injury but of the horror of the war experience or indicative of a pre-existing condition. It seems there was a determination in men to get on with their lives—some, writing in hospital after the war, further suggest that their injury was sustained in a just cause and they would not have taken any other path.6 Was this because the process of war took men from dull and repetitive jobs and exposed them to undreamed-of excitement? That it introduced them to new friends, whose comradeship developed all the more because of shared exposure to danger? Was it simply that men showed a typical British “stiff upper lip”—figuratively, as many had lost theirs? Certainly it is clear that the camaraderie of Sidcup was very positive and engendered a determination to continue life both successfully and without complaint.

Men were not completely unaffected by their injuries; there is testimony indicating that many were reluctant to be photographed in later life and a few were embarrassed by speech defects or problems when eating.

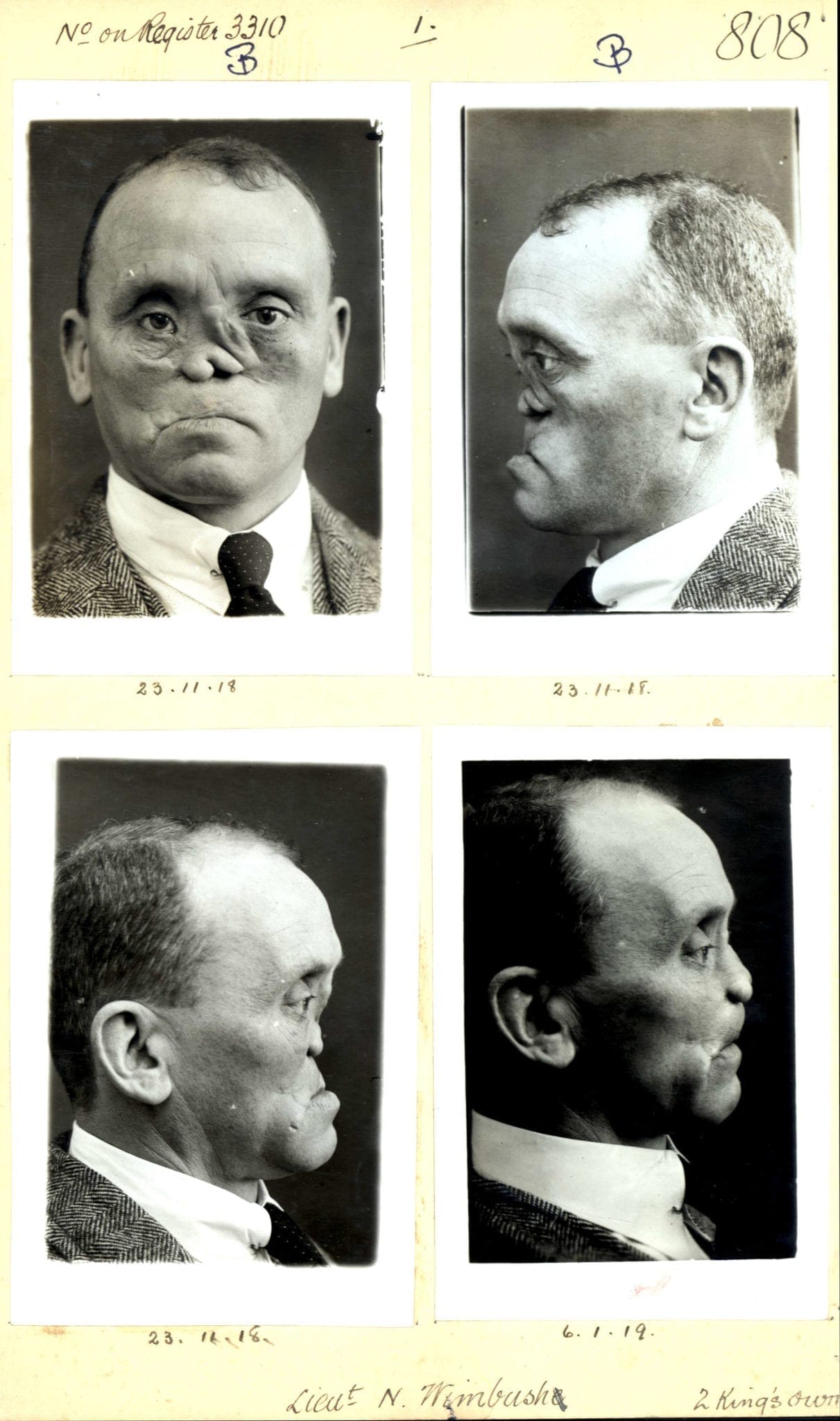

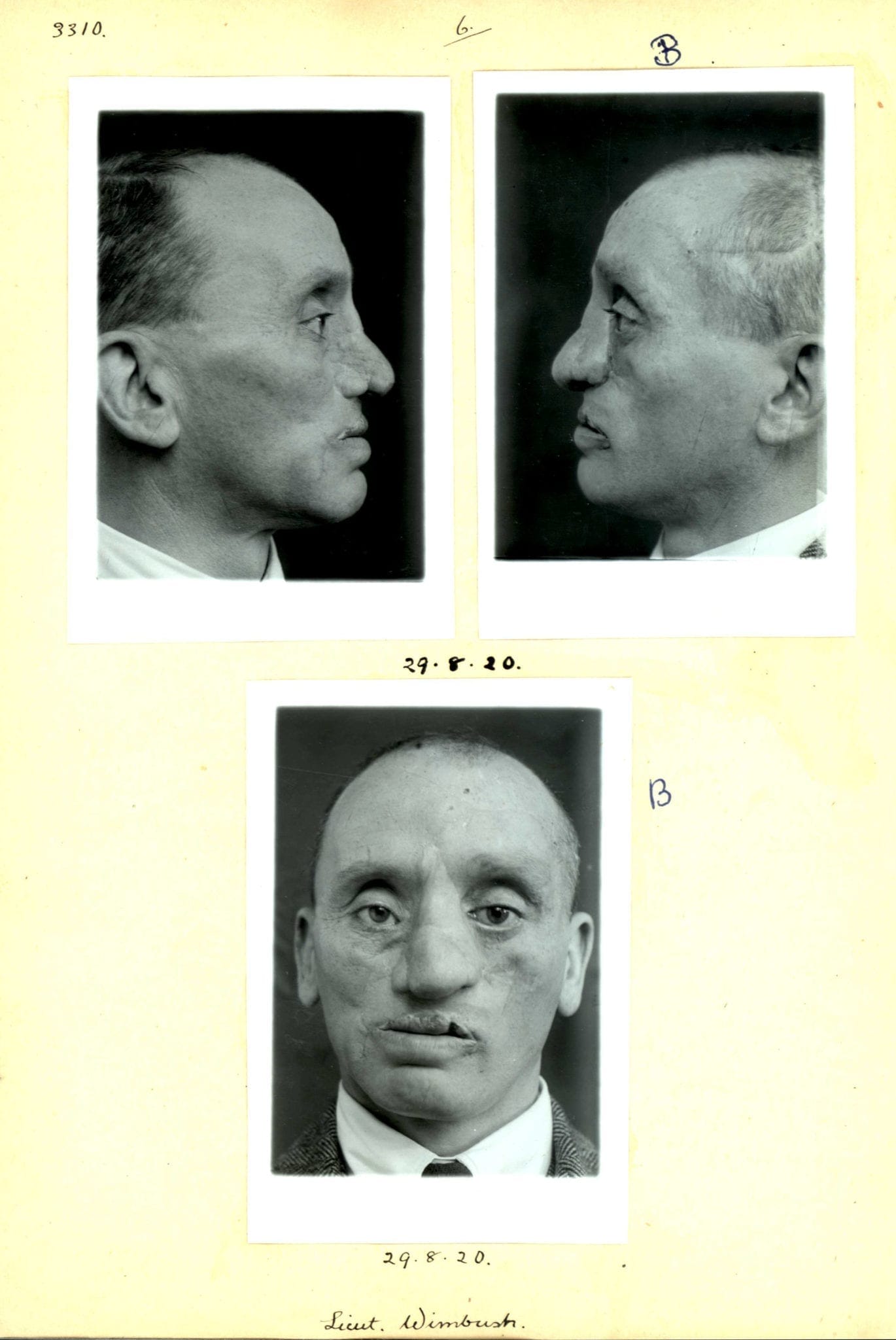

No self-help group was formed by the patients of the Queen’s Hospital, in contradistinction to the founding in France of the “Union des Blessés de la Face et de la Tête” (“Les Gueules Cassées”). I argue that Sidcup patients had no need. The concentration of facial injury patients in one place meant, effectively, that peer group support began at the point of admission. The surgical results were remarkable (figures 6 and 7) and there was psychological input from the staff and proper work rehabilitation. In France, however, none of these factors applied. Harold Gillies recorded his view that French patients’ appearance was horrible before intervention and ridiculous after. The same was true in Germany and Italy. Two Sidcup patients who returned from France and Germany to be treated later at Sidcup demonstrate the point; both were “finished” cases who demonstrate graphically the inadequacy of reconstruction (figures 8–11). After Sidcup they were greatly improved both in appearance and function. Also, on the continent there was no systematic system of follow-up and it is apparent that surgeons’ attitudes to their failures were very negative. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the injured took it upon themselves to develop their own support organization.

Recent conflicts have added a dimension to this discussion. While the First World War resulted in a large number of facial injuries among the military, changes in the patterns of warfare have tipped the balance towards civilian injury. But there is contemporary evidence that PTSD may be more of an issue to those who have been damaged by war experience and exposure without having sustained any significant or obvious physical injury.7

In conclusion, there is sufficient evidence from the testimony of Sidcup patients and their relatives to argue firmly that psychological disturbance as a result of facial injury in British patients from the First World War has been greatly overestimated. Reliance on the testimony of a small number of professionals who expected their charges to require concealment and to suffer stigma accordingly is misplaced. That expectation is not borne out by the men treated at Sidcup and is testament to the cosmetic and functional successes of the surgical techniques developed there.8

Figures 10 and 11. Lieut Wimbush: photographs taken on admission (surgery had been “completed” in Paris by Hippolyte Morestin)

and following almost 2 years of further surgery at Sidcup.

End notes

- Catherine Black, King’s Nurse – Beggar’s Nurse. London, Hurst & Blackett, n.d., 85-89

- Ward Muir, The Happy Hospital. London, Simpkin Marshall, 1918, 143-145

- www.gilliesarchives.org.uk

- Interviews with Joseph Pickard, Imperial War Museum, London. IWM 8946 (1986)

- A transcript of reports I have received is available on my website and is updated on receipt of further information

- The essays are in the Liddle Collection, University of Leeds (Liddle/WW1/GA/WOU34). Further discussion of this argument appears in my book “Faces from the Front” (Helion Press, 2017)

- Simon Weston (burned veteran of the Falklands conflict in 1982), personal communication

- See also Harold Gillies, Plastic Surgery of the Face, London, Henry Frowde, 1920 and Harold Gillies & Ralph Millard, The Principles and Art of Plastic Surgery, Boston, Little, Brown & Co, 1957. The former has been digitised and is available at https://archive.org/details/plasticsurgeryof00gilluoft/page/iii

Acknowledgements

Figures 4 and 6-11 are from the Archives of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and reproduced with permission. The others are from my own collection.

ANDREW N. BAMJI, MB, FRCP, qualified in medicine from the Middlesex Hospital, University of London in 1973, and was a consultant (rheumatology and rehabilitation) at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup for 28 years. He is the past President of the British Society for Rheumatology and an expert on medicine and surgery of the Great War. Gillies Archivist to the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons; author of “Faces from the Front: Harold Gillies, The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup and the Origins of Modern Plastic Surgery” (Helion Press, 2017) and “Mad Medicine: Myths, maxims and mayhem in the National Health Service” (KDP, 2019).