Andrea Lollo

New York, New York, United States

“Hereditary spherocytosis is a common inherited disorder that is characterised by anaemia, jaundice, and splenomegaly.”1

It was odd, of course, for a ten-year-old to have gallstones. It was even stranger for me to miss a full week of summer camp to sleep on the couch, swimming in and out of consciousness with a virus that would eventually lead to a diagnosis of hereditary spherocytosis.

I have had two blood transfusions in the past fifteen years, both precipitated by some unknown illness. Otherwise, spherocytosis is something I forget I have, much like my tongue ring or the mole on my face, until someone brings it up. If I ever mention I am feeling ill, my mother will demand to check my color. Along with gallstones, a side effect of the blood disorder is jaundice, which gets more severe when my oddly round red blood cells are suddenly under attack. Though the whites of my eyes have generally never been white, it took that week home from summer camp and my skin turning highlighter yellow for my parents to whisk me into the emergency department. I wish I could remember it (although not really), if only to see the family story-worthy expression on the nurse’s face who first saw me being wheeled in.

I don’t know if my siblings ever forgave me for having to be dragged into SickKids2 to get blood drawn. My older sister was terrified of needles, and my younger brother screamed as soon as the butterfly clip touched his arm. My parents were also tested, since hereditary spherocytosis is, in fact, hereditary. I must have gotten it from someone, although in my case, it turns out, I did not. My father insisted throughout my childhood that I must have been part of the X-Men, because I managed to mutate into gaining a hereditary disorder that I did not inherit. If I have children, they will have a 50% chance of having it too. So that is where the hereditary part comes in, I guess.

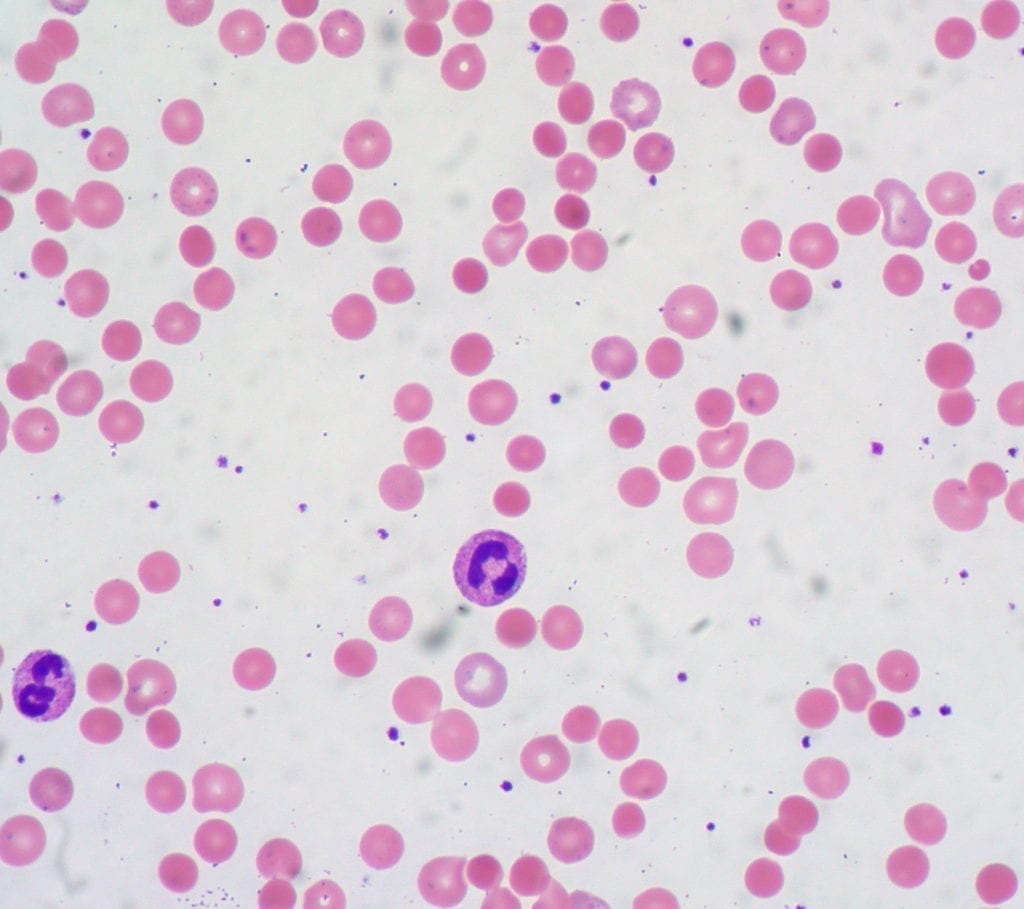

My blood is populated by spherocytes; red blood cells that are spherical rather than oval and concave as they should be. Once in a while, usually when I am sick, the spleen does a double take and notices this, mistakes these spherocytes for damaged or old blood cells, and casually starts destroying them. That would be fine if I had any other type of red blood cells, but I do not, so basically I am being drained of blood without it even going anywhere. Doctors have discussed having my spleen removed to prevent the problem, but apparently it is good for more than just freaking out and forgetting every once in a while that spherocytes are really all I have. It is time to head to the hospital if I am passing out from anemia or glowing yellow like I am radioactive. The treatment for a crisis is a blood transfusion, although that is not the first choice in trying to deal with whatever virus is causing the flare-up. The last time I needed a transfusion, I first went through tests for West Nile virus and meningitis, including a spinal tap, before a transfusion was given. Since my diagnosis as a child, I have had my gallbladder removed and a couple transfusions, but to date, the thing that annoys me most about my self-destructive mutant powers is how often my mom tells me that I “look yellow” and then violently jerks back my eyelids to check the level of jaundice in my whites, which I promise is always the same shade of bloodshot.

The only chronic treatment for hereditary spherocytosis is supplementing with folic acid, or eating an intense amount of folate-rich foods. I would be lying if I said I did either of those things, but considering the treatment is really just for the hemolytic anemia, it may not matter to me until one day when I am pregnant.

Nonetheless, as a horror fan and the daughter of a hematologist, I am quite a fan of blood; especially the pints that have been donated to me from strangers, who probably have no idea what degree of life-saving ability their time in the phlebotomy chair really has.

Also, “hemoglobin” sounds like “blood goblin” to me and I love that, even if I am generally super low on it.

End notes

- Perrotta, Silverio, Patrick G. Gallagher, and Narla Mohandas. “Hereditary spherocytosis.” The Lancet 372, no. 9647 (2008): 1411-1426.

- Toronto’s SickKids children’s hospital, where I spent the majority of my childhood.

ANDREA LOLLO is a writer of personal essays and fiction, as well as an archivist and podcast transcriptionist. She currently resides in New York City.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest