JMS Pearce

East Yorks, England

“…The remarkable individuality and discriminating tact of my old master made a deep and lasting impression on me, though I had not the faintest idea that it would one day lead me to forsake medicine for story writing.”

Arthur Conan Doyle is remembered worldwide as the creator of Sherlock Holmes. The Guinness World Records list Sherlock Holmes as the most portrayed film character, being played by seventy-five actors in 211 films. By highlighting the often neglected part played by his teacher and cynosure—the surgeon Joseph Bell—we can better understand what fired Conan Doyle’s creation, so real to the public that many later believed a living person, not a fictional character, had perished at the hands of Professor Moriarty.

There is vast literature about Sherlock Holmes, his author,1 and the memorabilia in the Sherlock Holmes Museum at 221B Baker Street and the Sherlock Holmes Society of London. But Holmes apart, Conan Doyle is of particular interest with his varied career as a doctor, writer, journalist, public figure, and advocate of spiritualism. Few would dispute that in Sherlock Holmes, together with his “straight-man” Dr. Watson, Conan Doyle started the art of detective fiction. From it emerged its later exponents: Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot, Maigret, Perry Mason, and Inspectors Wexford and Morse.3 But what aspects of his own history guided Conan Doyle to invent the greatest of all detectives?

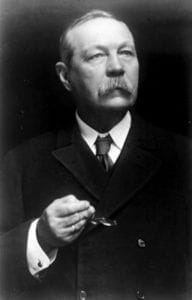

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) (Fig 1.) had a conventional Victorian background. He was born in Edinburgh into a prosperous Irish family and attended the Jesuit Stonyhurst College where he acquired a taste for the writings of Walter Scott and Thomas Babington Macaulay. He trained in medicine at Edinburgh University, graduating in 1881 and was awarded the MD in 1885 for his thesis An essay upon vasomotor changes in tabes dorsalis. Two men influenced his future fictional heroes. The physiologist William Rutherford inspired his Professor George Edward Challenger novels, but more famously the mind-boggling deductive powers of Joseph Bell, Professor of Surgery, inspired Conan Doyle’s idea of a detective using Bell’s diagnostic methods.2

Spanning a decade, Conan Doyle’s medical career was not entirely rewarding. He worked as a surgeon on an Arctic whaling boat and on a steamer traveling to West Africa. He moved in 1882 to Bush Villas in Elm Grove, Southsea on the English coast and worked as a general practitioner for eight years. In this period he wrote the first Sherlock Holmes stories: A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four. In 1891 he started an ophthalmology practice at 2 Upper Wimpole Street—a wholly unsuccessful, frustrating venture that ended his medical work and turned him to full-time writing.4

A Study in Scarlet was initially rejected but finally published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887. The historical novels Micah Clarke (1889) and The White Company (1891)—a medieval European adventure story about a company of archers of great chivalry, nobility, and strength—were his attempts to emulate Walter Scott. Meanwhile his Sherlock Holmes short stories appeared in The Strand Magazine and were so popular that he devoted himself to writing more such tales. But in November 1891 he wrote to his mother: “I plan to kill Holmes… He prevents me from thinking to better things.” After his twenty-sixth story, in 1893, he killed Holmes after a terrifying fight with James Moriarty at Meiringen’s Reichenbach Falls. Despite a fierce public outcry, Conan Doyle refused to resurrect him, hoping to concentrate on more serious writing. Further public protests eventually prompted the return of Holmes in more stories collected under the titles The Return of Sherlock Holmes, His Last Bow, and finally The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, which ended in 1927.

Conan Doyle, a serious student of classical literature, wrote twenty-one novels and 188 short stories. He also wrote poetry, plays, essays, medical papers, and letters5 about remarkably diverse topics.6 It was one of these, not the Sherlock Holmes tales, which led to his knighthood (KBE) in 1902, awarded for his services to the Crown during the Boer War, especially his accounts of The Great Boer War and The War in South Africa: Its Causes and Conduct (1902).

Paradoxically for such a logical mind, he became obsessed by the occult and spiritualism. Joining the British Society for Psychical Research he crusaded through writings and lectures on the psychic revelations of spiritualism.7

Conan Doyle was an able amateur sportsman. But he never forgot his mother telling him as a boy tales of chivalrous knights and family honor. He was ever a great romantic—witness Through the Magic Door (1912) that told of the romantic joys of exploring the past in your private library.

Close the door of the room behind you, shut off with it all the cares of the outer world, plunge back into the soothing company of the great dead, and then you are through the magic portal into that fair land wither worry and vexation can follow you no more.

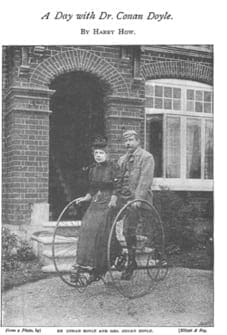

His compassion was shown in March 1885 when he came to the rescue of the Hawkins family. The boy Jack was terminally ill with meningitis and epilepsy, and the family was threatened by eviction. Conan Doyle took Jack Hawkins into his Southsea home. However, he fell in love with Louisa, Jack’s sister, and they were happily married in August 1885. (Fig 2.) Louisa bore Mary Louise and Kingsley, but sadly died of tuberculosis in 1906 despite Conan Doyle’s unselfish and devoted attention. After Louisa’s death he married Jean Leckie; they had three children. This marriage too was a happy one and lasted until his death of a heart attack on 7 July 1930.

A further insight into Conan Doyle the man is provided by his valedictory address that stated his writings provided “a distraction from the worries of life…that can only be found in the fairy kingdom of romance.”8

Joseph Bell

Joseph Bell (Fig 3.) was an Edinburgh surgeon whom Conan Doyle met as a medical student in 1877, serving as his dresser/clerk in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.9 Doyle was entranced by Bell’s unusual powers of observation and deduction at the bedside in ward eleven and in the clinic.10 That this proved to be the inspiration for the detective skills of Sherlock Holmes11 is attested to in a little known letter written by Conan Doyle in May 1892 to Dr. Joseph Bell.9

Bell wrote to The Strand Magazine in 1892 with characteristic modesty:

…Dr. Doyle’s genius and vivid imagination has on this slender basis made his detective stories a distinctively new departure but he owes much less than he thinks to yours truly Joseph Bell.

Curiously, Bell later inveighed against Sherlock Holmes, but not his creator, for in 1901 in a rare, unkindly vein he wrote:

Why bother yourself about the cataract of drivel for which Conan Doyle is responsible? I am sure he never imagined that such a heap of rubbish would fall on my devoted head in consequence of his stories.12

Joseph Bell (1837–1911) was the last of a famous surgical dynasty in Edinburgh where he studied and qualified in 1859.9 He was to succeed James Syme (1799–1870), his hero and mentor. A devout churchman, Bell was a brilliant, caring craftsman and surgeon, and also a dedicated mentor of nurses. He served as a personal surgeon to Queen Victoria in Scotland, and was President of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh (1887–1889). For twenty-three years he edited the Edinburgh Medical Journal and his Manual of the Operations of Surgery (1866) ran to seven editions.

His powers of observation of trifling details, and his analysis of handwriting and regional dialects, proved the vital tools in his legendary diagnostic acumen. Doyle noted:1

Bell’s skills were to be dramatically duplicated in Conan Doyle’s detective. Bell described his methods to The Strand Magazine‘s journalist Harry How:1

The patient, too, is likely to be impressed by your ability to cure him in the future if he sees you at a glance know much of his past, For instance, physiognomy helps you to nationality, accent to district, and, to an educated ear, almost to county. Nearly every handicraft writes its sign-manual on the hands. The scars of the miner differ from those of the quarryman. The carpenter’s callosities are not those of the mason. The shoemaker and the tailor are quite different. The soldier and the sailor differ in gait — though last month I had to tell a man who said he was a soldier that he had been a sailor in his boyhood. The subject is endless. The tattoo marks on hand or arm will tell their own tale as to voyages. The ornaments on the watch chain of the successful settler will tell you where he made his money. . . . Carry the same idea of using one’s senses accurately and constantly, and you will see that many a surgical case will bring his past history, national, social, and medical, into the consulting-room as the patient walks in.

This master of diagnostic deduction emphasized “the vast importance of little distinctions, the endless significance of the trifles. …In fact, the student must be taught to observe.”1

Bell was also an amateur poet, keen cricketer, tricyclist, and bird-watcher.13 His friend, the Shetland folklorist Jessie Margaret Saxby, described a devout man, his modest life filled with acts of humanity, generosity, and personal sacrifices for both patients and friends:

a strongly marked personality, a likeable, sympathetic temperament. In the midst of his arduous duties he found time to devote to the instruction of nurses …He was one of the originators of the Hospital for Incurables, …His interest in this work was of the keenest, and greatly appreciated by the sufferers whose burdens he lightened by his kindly sympathy and cheering words. His tenderness over the little maimed lives in the Cripples Home was womanly in its intuitive comprehension.12

His skills caused him to be consulted in many police investigations including the Jack the Ripper murders of Whitechapel.

He died in 1911 and was buried in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery next to Edith, his beloved wife. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh has an impressive archive and collection of his memorabilia.

Without Sherlock Holmes few would remember Joseph Bell; without Joseph Bell, Conan Doyle could not have created Sherlock Homes. We should remember Bell as an exemplary, humane surgeon, and for inspiring a series of the first, best, and still popular detective stories in the long history of that genre.

References

- How H. A day with Dr. Conan Doyle. The Strand Magazine 1892; pp. 3-9 https://nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/sffaudio-usa/usa-pdfs/ADayWithDr.ConanDoyleByHarryHow.pdf.

- Dunea G. Joseph Bell, supreme diagnostician. Hektoen Int. Hektorama, Fall 2014.

- Davies DS. Introduction to: A Study in Scarlet By Arthur Conan Doyle. Herts, Wordsworth editions Ltd, 2004.

- Doyle AC. Memories and adventures. London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1924. http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks14/1400681h.html.

- The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopaedia 22 May 1859, Edinburgh https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:Letter-acd-1892-05-04-bell-p1.jpg.

- Ibid. Chronology. https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=Sir_Arthur_Conan_Doyle:Chronology.

- Shulman MD. Arthur Conan Doyle and the romance of medicine. Hektoen Int. Hektorama Physicians of Note, Spring 2018.

- Doyle AC. St Mary’s Hospital: Introductory address on “The Romance of Medicine.” Lancet. 1910; 1066-1068.

- Liebow E. Dr. Joe Bell: Model for Sherlock Holmes. Wisconsin, Popular Press. 2007. (originally Bowling Green Univ Popular Press 1982.) https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=i5nb6TywMIQC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=joseph+bell+sherlock+holmes&ots=jOc54kCX8b&sig=MjlxFiKp8P-4dYx3Ih-KDrOeRwo#v=onepage&q=Sherlock&f=false.

- Godbee DC. Joseph Bell (1837–1911): A Clinician’s Literary Legacy. Journal of Medical Biography, 1999;7:166-170.

- Accardo P. Diagnosis and detection : the medical iconography of Sherlock Holmes. London: Associated University Presses, 1987.

- Saxby Jessie ME. Joseph Bell; an appreciation by an old friend. Edinburgh ;Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier 1913.

- ‘Conan Doyle Info.’ https://www.conandoyleinfo.com/sherlock-holmes/sherlock-holmes-and-dr-joseph-bell/.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is an emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary.