Craig Stout

Aberdeen, Scotland

|

| The Battle of Waterloo (1815), oil painting by William Sadler. Pyms Gallery, London. |

The Napoleonic Wars (1799 to 1815) brought great upheaval and turmoil to Europe, with as many as 2.5 million soldiers and 1 million civilians losing their lives. French military physicians, principally Dominique Jean-Larrey, made significant contributions to medicine, saving many lives and helping to develop modern medical practices for future generations.

The abominable conditions and casualties during campaigns in Egypt and Syria where one third of the French troops died in battle or illness, prompted Jean-Larrey to develop the modern system of triage. Triage is defined as “the assignment of degrees of urgency to wounds or illnesses to decide the order of treatment of a large number of patients or casualties.”1 Regardless of rank and nationality, soldiers were categorized into one of three groups: dangerously wounded, less dangerously wounded, and slightly wounded.2 Jean-Larrey’s concept was that “those dangerously wounded must be attended first, entirely without regard to rank or distinction, and those less severely wounded must wait until the gravely hurt have been operated and addressed.”3 Similar categories are still seen in practice today, such as in the “Sort, Assess, Life-Saving interventions, Treatment and/or Transport (SALT)” method of triage in the US.4

Although the first use of modern triage was deployed in the Battle of Jena (1806), this had been refined from the original practice of “Napoleonic triage.” Developed between 1797 and 1801, Napoleonic triage gave priority to “treating sick and wounded soldiers who were able to fight again on the battlefield” and soldiers who were of a higher rank.5 Napoleonic triage was different from the procedure used by Jean-Larrey because the priority was to sustain military strength throughout campaigns rather than aiming to save as many lives as possible.

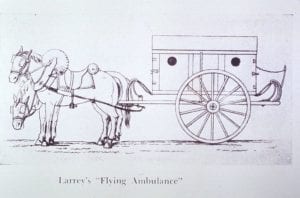

The ambulance transport system developed by Jean-Larrey was another significant medical advancement used by Napoleon’s armies. Before the establishment of the ambulances volantes (flying ambulances), ambulancias or military hospitals as we now know them, were ordered to remain “one league distant from the Army.”6 Consequently, injured soldiers were abandoned on the battlefield until the fighting subsided, then gathered from a convenient location for transport to a field hospital. As Jean-Larrey put it: “The number of wagons interposed between them and the army and many other difficulties so retarded their progress, that they never arrived in less than twenty-four or thirty-six hours, so that most of the wounded died for want of assistance.”7

|

| Ambulance Volante (flying ambulance) to evacuate casualties from the battlefield. |

The inadequate health and sanitary conditions faced by soldiers left on the field led Jean-Larrey to design a rapid evacuation system for injured soldiers. The ambulances were light, wooden horse-drawn carriages that could hold two wounded combatants. The ambulances were split into units of three divisions, with twelve carriages and 113 men per division.8 Jean-Larrey expressed that “with these ambulances, the most rapid movements of the advanced guard of an army can be followed up and, when necessary, they can separate into a great many divisions… affording the earliest assistance on the field of battle.”9 Deployed throughout the French military from 1799, these carriages carried the wounded to larger vehicles for transport to field hospitals at the rear of the battle. Medical officers accompanying the carriages also carried portable surgical instruments, field dressings, and some medications on their saddles as well as in the carriages, greatly expanding the flexibility of medical personnel.10 The ambulances were a tremendous success when used together with the system of triage, and substantially diminished the number of French deaths during Napoleon’s campaigns. Furthermore, with Jean-Larrey’s steadfast moral values and regard for all human life, he treated friend and foe equally. This principle is enshrined today in the Geneva Convention.

Several advances in the treatment and understanding of hypothermia were also developed by Jean-Larrey during the Napoleonic Wars. Injuries due to cold temperatures have been common throughout history and were reported by figures such as Xenophon, Hannibal, Galen, Aristotle, and Hippocrates. Each described frostbite and cold-related sickness as one of the most detrimental ailments to afflict their armies.11

It was not until Jean-Larrey’s research on hypothermia and his introduction of its use as a treatment that cold-related injury began to be more properly understood. In his memoir, Jean-Larrey described observations made during campaigns in Spain and Russia. He recognized that soldiers who remained in conditions of -15oC would not complain of any symptoms, but once the temperature dropped to -18oC and beyond, soldiers would lament of painful paresthesia and stiffness.12 Jean-Larrey was the first to speculate, from witnessing soldiers affected by the cold but near to fire, that a rapid change in temperature could lead to gangrene. Accordingly, to treat cold related injuries he advised soldiers to first rub the affected parts with snow followed by a tonic (brandy/wine/vinegar), and then warm themselves at approximately 0.5-1o per hour.13 He noted that “heat suddenly applied to the parts which have been rendered torpid by cold may be considered as the exciting cause.”14

Jean-Larrey also discovered and developed the technique of therapeutic hypothermia after years of campaigns in which he observed the detrimental effects of atrocious weather. Jean-Larrey realized soldiers had a greater tolerance for pain and bled less when they remained cold compared to those who had been in more favorable weather.15 Furthermore, he recognized that not only did cold help to reduce the pain of amputations, but it could also be used to prevent shock.16 Today, therapeutic hypothermia is used by healthcare professionals in the treatment of cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, hypoxic-ischemia, stroke, and other conditions.

|

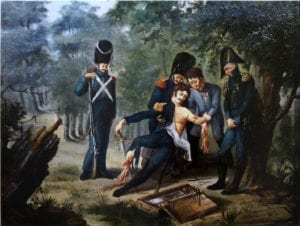

| Jean-Larrey amputating the arm and leg of Colonel Rebsomen at Hanau (1813). G. Garitan. |

Having observed the quick spread of dead tissue in severely injured limbs, Jean-Larrey firmly believed that early amputation was required to avoid the propagation of infection. Despite the advice of many of his peers, Jean-Larrey’s methods considerably reduced fatalities from diseases such as sepsis and tetanus.17 However, it was not until Louis Pasteur’s research on micro-organisms and the subsequent development of aseptic surgical techniques by Joseph Lister in 1865 that secondary infections following operations began to be understood and prevented. Today, amputation is used rarely and only when an extremity cannot be salvaged.

Described anecdotally throughout history, it was not until the observations and recordings of French doctors during and after the Napoleonic Wars that soldiers’ mental health was more seriously considered. However, treatment remained limited. Several factors may have led to the lack of research into mental health: ignorance of mental health conditions, stigma for diseases without physical symptoms, shame, and the idealization of brave soldiers.18 Today the word “nostalgia” implies a yearning for a place or time in the past, but the term was used by the French doctors of this era to define serious mental health conditions such as depression and psychosis. The term nostalgia takes its roots from “homesickness,” and the condition had been recognized for a long time but inadequately understood. As early as 1569 Ludwig Pfyffer, leader of the Swiss Guard in France, described the case of a soldier who died of homesickness.19 The nineteenth century French military physician Tyrbas de Chamberet, stated nostalgia was “endemic among the military” and “far more common than scurvy and no less murderous than typhus.”20

This definition of nostalgia included symptoms of deep sadness, loss of appetite, poor sleep, anxiety, heart palpitations, incontinence, and even death. The French doctor Allard correctly deduced that the origins of nostalgia are not found in the organs affected but come from the brain. Jean-Larrey agreed, believing “the intense emotions experienced by the nostalgic are transmitted in the organs through the nervous system.”21 However, the treatment methods were awfully insufficient. In his book Clinique Chirurgicale Jean-Larrey proposed military exercises and activities to help distract soldiers from their troubles.22 Music was also considered an effective preventative treatment. He noted that “the military music that can be played during meals or at recess time, would greatly contribute to liven up the spirit of the solider and to divert the sad and sinister reflections…”23 However, other therapies offered by Napoleon’s doctors focused on treating nostalgia as if it were a physical health condition. Jean-Larrey advised “bleeding and cautery, ice on her head, warm baths, cupping on the back and abdomen, frictions and embrocation camphor” as treatments.24 Allard suggested “leeches, tonics such as coffee, tea and especially wine… provides rest and inspires gaiety.”25 Lastly, while it was acknowledged that many soldiers were plagued by nostalgia, physicians such as Percy, the chief surgeon of the Grand Armée, believed that soldiers used the malady to avoid their military duties. Percy noted “among the many diseases simulated by young people who wish to escape military exercises, yes who want to go to their parents, none is perhaps more frequent than nostalgia.”26 While some soldiers may have fabricated symptoms of nostalgia in this way, Percy’s comments suggest doctors at the time still viewed the condition with a degree of disdain that was not afforded to serious physical ailments. Consequently, although mental health diseases were first properly acknowledged during this era, effective treatment and attitudes towards them barely advanced during the Napoleonic Wars.

The progress made by French doctors during the Napoleonic Wars had a profound effect on the advancement of medicine. Their work, born from the chaos of immense conflict, saved countless lives and paved the way for future medical breakthroughs and progress. Of particular note is Jean-Larrey’s contribution – shortly before his death Napoleon articulated: “If the army were to raise a monument to the memory of one man it should be to that of Jean-Larrey.”27

References:

- Oxford University Press, The Oxford Mini-Dictionary (1991), p567

- Nakao H, Ukai I, Kotani J. ‘A review of the history of the origin of triage from a disaster medicine perspective’, Journal of Japanese Association for Acute Medicine, 2017; 4(4): 379-84

- Brewer LA. ‘Baron Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842). Father of modern military surgery, innovator, humanist.”, The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 1986; 92(6): 1096-98

- Cone DC, Serra J, Burns K, Macmillan DS, Kurland L, Van Gelder C. ‘Pilot test of the SALT mass casualty triage system.’, Prehospital Emergency Care: official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors, 2009; 13(4): 536-40

- Nakao H, Ukai I, Kotani J. ‘A review of the history of the origin of triage from a disaster medicine perspective’, 379-84

- Larrey DJ. Campaign on the Rhine. In: Hall R, ed. Memoirs Of Military Surgery And Campaigns Of The French Armies. Baltimore; 1814: p.23

- Larrey DJ. Campaign on the Rhine. In: Hall R, ed. Memoirs Of Military Surgery And Campaigns Of The French Armies. Baltimore; 1814: p.23

- Skandalakis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. ‘To afford the wounded speedy assistance: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon, World Journal of Surgery, 2006; 30(8): 1392-99

- Larrey DJ. Campaign on the Rhine. In: Hall R, ed. Memoirs Of Military Surgery And Campaigns Of The French Armies. Baltimore; 1814: p.83

- Skandalakis PN, ‘To afford the wounded speedy assistance: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon, 1392-99

- Remba SJ, Varon J, Rivera A, Sternbach GL. ‘Dominique-Jean Larrey: The effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance’, Resuscitation, 2010; 81(3): 268-71

- Remba SJ. ‘Dominique-Jean Larrey: The effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance’, 268-71

- Varon J, Acosta P. ‘Therapeutic hypothermia’, Chest, 2008; 133(5): 1267-74

- Remba SJ. ‘Dominique-Jean Larrey: The effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance’, 268-71

- O’Sullivan ST, O’Shaughnessy M, O’Connor TPF, ‘Baron Larrey and cold injury during the campaigns of Napoleon’, Annals of Plastic Surgery, 1995; 34(4): 446-49

- Remba SJ, ‘Dominique-Jean Larrey: The effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance’, 268-71

- Welling DR, Burris DG, Rich NM. ‘The influence of Dominique Jean Larrey on the art and science of amputations’, Journal of Vascular Surgery, 2010; 52(3): 790-93

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2019; 3(1): 57-62

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Larrey DJ, Recueil de mémoires de chirurgie, Paris: 1812; pp.162-63

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Larrey DJ, Recueil de mémoires de chirurgie, Paris: 1812; pp.191

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Josse E. ‘La nostalgie des soldats des guerres d’Empire’, 57-62

- Richardson RG, ‘Larrey-what manner of man?’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1977; 70(7): 490-94

CRAIG STOUT is a 4th year medical student at the University of Aberdeen. He grew up in Glasgow, Scotland and currently lives and studies in Aberdeen. His clinical interests include psychiatry, emergency medicine, and cardiology.

Spring 2019 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply