Chris Clark

Exeter, United Kingdom

“Every human being tells a story even if he never speaks.”1

Two paintings hang next to each other in the sumptuous Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome: The Rest on the flight to Egypt and Penitent Magdalen. Both are early works by Caravaggio, and these two diverse biblical women appear to have been modelled by the same sitter.2 The recognition of individual models in painting highlights two distinguishing features of paintings that date from the time of the Renaissance onwards; the emergence of the individual and the development of realism.3 Whilst depictions of disease date back to the thirteenth century, it is only since the Renaissance that we might expect artists to have reliably depicted signs of disease or illness, as characteristics of their sitters.4

That this process occurred is not a new suggestion; Aldersey-Williams has remarked on the phenomenon of physicians “stalking the art galleries of the world, searching out artistic depictions of their medical specialty,” as evidenced by Strauss and colleagues who previously identified twenty-three skin lesions in a systematic survey of the National Portrait Gallery, London.4,5 Despite obvious risks of over-diagnosis, this pastime has generated a stream of more or less speculative diagnoses, such as, for example, suggestions that Michelangelo’s Night or Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Woman (also known as La fornarina), appear to have breast cancer.6,7 Modern developments in medicine mean that the florid, classical appearances of clinical signs of certain conditions, at least in the developed world, are now much rarer. However, it is also worth considering other contexts, such as environmental or social conditions, when evaluating signs of disease depicted in paintings.8 These are less often discussed than the diagnoses themselves, yet can contribute to the understanding of our observations, as demonstrated through the following examples.

Goiter, a visible and palpable swelling of the thyroid gland, has been observed in artworks dating back to the earliest cultures, stimulating medical debate as to the veracity of such images and their relationship to contemporary illness.9 Art has been seen as one source of evidence for studying the history of goiter,10 however Renaissance artists introduced new degrees of realism, facilitating consideration of the underlying causes of this condition. Intriguingly in Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith and her Maidservant (1613) she portrays Judith as a self-portrait of the artist, including an obvious and intentional goiter.11 Curiously or coincidentally the earlier “lost” Caravaggio (Judith Beheading Holofernes; 1604-5) depicts Judith as an elderly woman, but with a prominent multinodular goiter.12 Caravaggio’s work was known to have influenced Gentileschi’s so perhaps we should be cautious in concluding that Artemisia suffered from any thyroid disease.

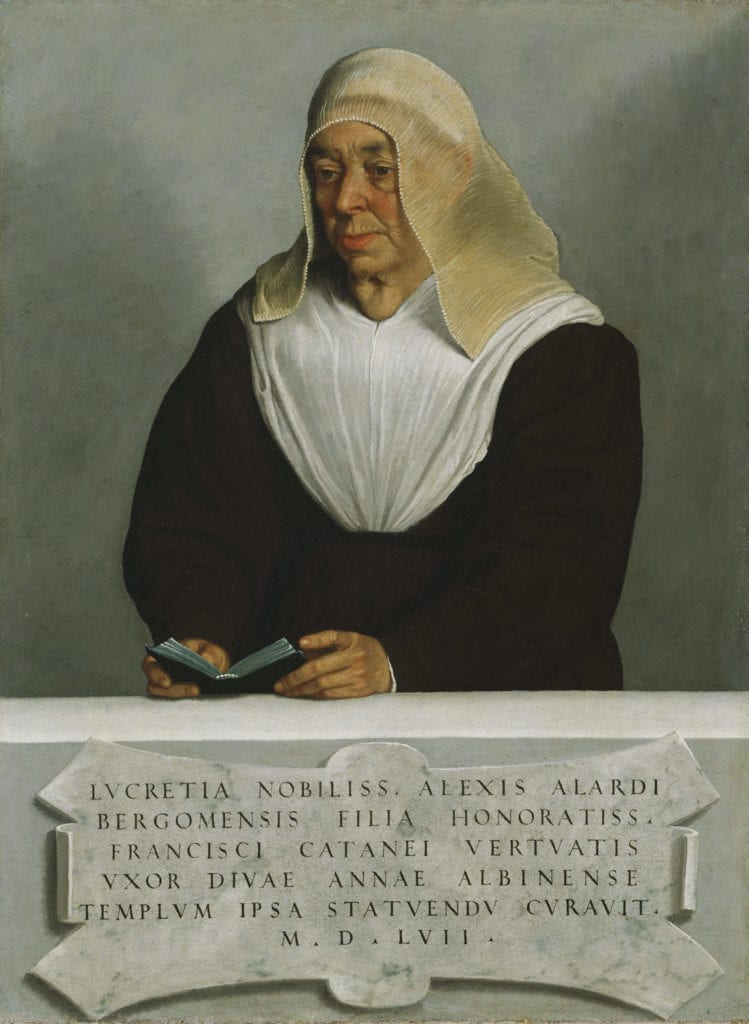

Giovanni Battista Moroni was renowned for the naturalism of his portraits, anticipating the realism of Caravaggio.13 In his 1557 portrait of Lucrezia Vertova Agliardi, he carefully depicts her prominent goiter (Figure 1). She was the foundress of the Carmelite monastery of Sant’Anna in Albino, Bergamo. (1525), where Moroni worked. Goiter has varied causes, including iodine deficiency (causing multinodular goiter). This was more prevalent in iodine deficient areas, such as the Alps and surrounding areas, and typically in places distant from the coast, as is Bergamo. Ferriss has also proposed that poverty or lower social class could be linked to goiter, and it was sometimes regarded as a sign of poor character, perhaps leading to its exaggeration in some images to emphasize the character of a subject in history painting.14 Nevertheless the decline in the incidence of goiter through the ages has been attributed, in part, to improved nutrition and decline in endemic goiter in Western Europe.14,15

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition that can also lead to as goiter, typically as a smooth thyroid swelling, and occurring more often in younger women. This could even be regarded as a feature of beauty,16 however women also undergo a normal physiological enlargement of their thyroid gland at puberty, suggesting that goiter may simply be more common at a stage of life associated with beauty.17 This is apparent in Laurent Pécheux’s depiction of a serene onlooker in his large 1784 depiction of Pietro Moriconi baptizes Lamberto son of the king of the Balearics hanging in the cathedral of St. Maria Assunta in Pisa (Figure 2).

Another interesting painting in Pisa cathedral is The Rescue of the Head of St. Torpé by Cignaroli Giovani Bettino (1706-1770). Torpes was a Christian martyr; legend tells that the emperor Nero had him decapitated after he declared himself a Christian. Torpes’ head was thrown into the river Arno and later claimed by Pisa, and this is the scene depicted in the canvas (Figure 3). Incidentally he also gave his name to Saint-Tropez in France, where his body washed up.

The elderly man reaching for Torpes’ head shows some signs of anemia; his face appears pale, and his fingernails show koilonychia, a flattening or concave spooning of the nails characteristic of iron deficiency anemia (Figure 4). Inadequate intake of iron has been described as the commonest nutritional deficiency in the world, and there is evidence of koilonychia dating back to Roman votive sculptures such as the “Lydney Hand.”18

Social conventions on diet ensured that meat and vegetables, important sources of iron, tended to be consumed by those of higher social standing, whereas our anonymous model, probably posing to earn some income, was most likely restricted to a cereal based diet, and may well have suffered from iron deficiency.19 Anemia is more commonly seen in paintings of younger women than our elderly model, perhaps because portraits of younger women were more commonly commissioned in families. For example, Leonardo da Vinci’s Portrait of Ginevra dé Benci, a well-known Florentine beauty, possibly commissioned for her sixteenth birthday, has been suggested to have the pallor of iron deficiency anemia, although some consider that this may be no more than the fading of pigments over time.20 Historically, anemia often appears confused with chlorosis; a diagnosis more commonly documented but disappearing in the early twentieth century. It was characterised by a greenish tinge to the skin and associated with younger women; however, this may have simply been profound iron deficiency, engendered by an iron-poor diet.21

In summary, these two examples show how the introduction of realism to painting during the Renaissance means that can we recognize stigmata of disease in the subjects of portraits, but also in those models or sitters on whom the paintings are based. This offers us the opportunity to speculate on the chronic illnesses and conditions that these “ordinary” people carried with them in their daily lives, allowing us a window onto prevalent conditions of the time. Once attuned to this possibility there is always a risk of over-imagination and over-diagnosis; competing explanations based on artistic expertise and techniques should always be considered before concluding that we have, indeed, observed signs of a genuine historical disease. However, remaining open to inquiry about such observations adds another facet to our appreciation of fine works of art.

References

- Naish JM, Read AE, Burns-Cox CJ. The clinical apprentice : a handbook of bedside methods. 5th ed. by John M. Naish, Alan E. Read and Christopher J. Burns-Cox .. ed. Bristol: J. Wright 1978.

- Guide to Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. 2012 ed. Rome: Arti Doria Pampilj S.r.l. 2012.

- Brotton J. The Renaissance : a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006.

- Strauss RM, Marzo-Ortega H, Goulden V. Skin abnormalities in the National Portrait Gallery. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2004;18(5):566-68. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01024.x

- Aldersey-Williams H. Anatomies : the human body, its parts and the stories they tell. London: Penguin 2013

- Stark JJ, Nelson JK. The breasts of “Night”: Michelangelo as oncologist. N Engl J Med 2000;343(21):1577-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432118

- Baum M. La Fornarina: breast cancer or not? The Lancet;361(9363):1129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12863-2

- Emery AE. Medicine, artists and their art. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1997;31(4):450-5.

- Accorona R, Huskens I, Meulemans J, et al. Thyroid Swelling: A Common Phenomenon in Art? European Thyroid Journal 2018;7(5):272-78. doi: 10.1159/000488315

- Merke F. The history of endemic goitre and cretinism in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries. Proc R Soc Med 1960;53:995-1002.

- Sterpetti AV. How the art in Rome represented personages with goitre. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2016;32:e28-e29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.023

- Traversari M, Rühli FJ, Gruppioni G, et al. The “Lost Caravaggio”: a probable case of goiter in seventeenth-century Italy. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2016;39(10):1203-04. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0492-y

- Facchinetti S, Galansino A, Pisvin K, et al. Giovanni Battista Moroni. London: Royal Academy of Arts 2014

- Ferriss JB. The Many Reasons Why Goiter Is Seen in Old Paintings. Thyroid 2008;18(4):387-93. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0301

- Costa A, Mortara M. A review of recent studies of goitre in Italy. Bull World Health Organ 1960;22:493-502.

- Sterpetti AV, Fiori E, De Cesare A. Goiter in the Art of Renaissance Europe. The American Journal of Medicine 2016;129(8):892-95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.04.015

- Perkins P. Art and the thyroid gland. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2011;104(5):185-85. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110052

- Poskitt EM. Early history of iron deficiency. British journal of haematology 2003;122(4):554-62. [published Online First: 2003/08/06]

- Gentilcore D. Food and health in early modern Europe : diet, medicine and society, 1450-1800. London: Bloomsbury 2016

- Hoenig LJ. Dermatology in the Artwork of Leonardo Da Vinci. JAMA Dermatology 2013;149(1):73-73. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.917

- Crosby WH. Whatever became of chlorosis? JAMA 1987;257(20):2799-800. [published Online First: 1987/05/22]

CHRIS CLARK, PhD, FRCP, FRCGP, is a practicing and academic general practitioner in Devon, England. He has lived and worked in the same rural community for twenty five years. His research interests include primary care and rural practice, but he specializes in research on measurement of blood pressure and organization of care in hypertension. He represents primary care on various international bodies.

Leave a Reply