David Jeffrey

Edinburgh, Scotland

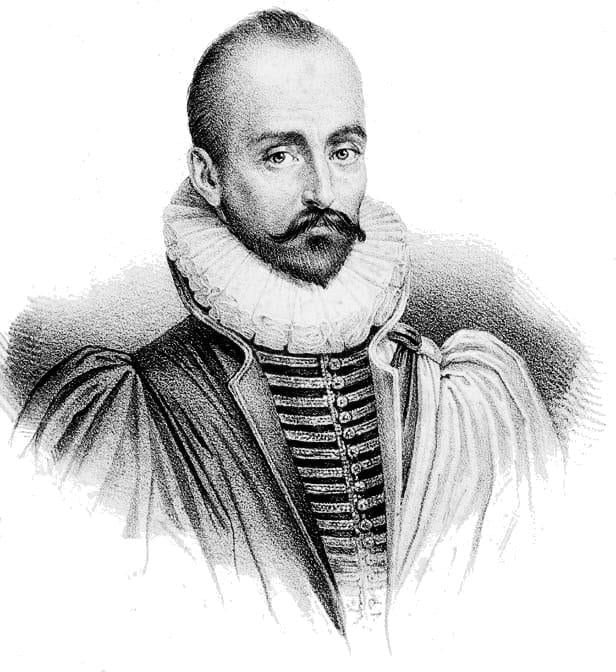

The term empathy was coined a little over a hundred years ago and since then its definition has evolved. At first empathy was regarded as a sharing of emotions, but modern medicine emphasizes cognitive aspects of the concept.1 Regarding the sharing of emotion with suspicion has led to a form of professionalism known as “detached concern.”2 Today there is concern that doctors lack empathy and that medical students lose empathy during training. A gap exists in clinical practice between evidence-based medicine and empathy-based medicine.3 Michel de Montaigne’s (1533–92) Essays provides insights into the process of connecting with other people, which can help doctors to connect emotionally with patients. Since classics are reinterpreted by every generation, it is timely to revisit Montaigne’s Essays, presenting his attempts (essais) to find a better way to connect with others.4

The relationship between doctor and patient involves empathy. It includes an awareness of the fallibility of perception and it is affected by context. Montaigne believed that the mind and body were intimately linked, restricting the ability to distance oneself from emotion. He was a humble man who was accepting of his ignorance, asking, “What do I know?”5 Awareness of one’s vulnerability is integral to emotional connection with another person. Montaigne questioned smug human superiority and was critical of hierarchies.

He went to great lengths to try to see the other person’s point of view. He asked, “When I am playing with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?”5 For Montaigne, the self and the cat move from isolated states to become one. William Osler (1849–1919) claimed that by excluding emotions, doctors gained a special objective insight into the patient’s suffering.6 In adopting this “detached concern” model for medical practice, emotions may be seen as a risk to patient safety. Consequently, some doctors believe that the suffering of patients should be handled with detachment.7 However, Montaigne challenges this view and is joined by modern authors who maintain that there is little evidence that establishing an emotional connection with a patient is harmful.2 Halpern argues that sharing the patient’s suffering is part of empathy, not simply labelling an emotional state.8 She advocates that the doctor adopt a stance of “engaged curiosity” in which understanding the patient’s individual perspective is combined with emotionally engaged communication.9

Shapiro claims that medical education promotes professional “alexithymia,” a term used to describe people who have difficulty processing emotions.10 It is not sufficient to train students to be empathetic and then expect them to work sensitively in situations where they are stressed. If psychosocial issues are given a higher priority in clinical practice and medical education, the empathy gap may be reduced.

Montaigne was one of the first writers to appreciate that non-verbal body language is central to establishing connection with another person. He wanted proximity, to bring people together in presence as well as with language. Emotional and physical distance are bridged in the physician’s touch. Montaigne argued that human relations are a rich source of knowledge of ourselves and others. He suggested that no matter how we try to distance ourselves from emotions, we can never cut ourselves off from the influence of others. Montaigne saw human beings as possessing a capacity for sympathy, which gives our lives meaning.5

Empathy requires effort; sharing emotions with patients may be emotionally draining. Montaigne stressed that we all need a sanctuary, a room at the back of the workplace, where we can be ourselves. In modern healthcare settings such retreats are in short supply.

Empathy becomes even more relevant in end-of-life care, where it is critical to ascertain the patient’s wishes. Empathy may involve doctors sharing uncertainty with patients. Montaigne gives us ways of handling uncertainty: “All that is certain is that nothing is certain.”4 He had an ability to consider opposing views while suspending judgement between them. His priority was to understand, rather than to judge. This allowed him to be open to fresh possibilities and to see the world from another’s perspective. Taking an other-orientated perspective prevents the doctor from losing sight of the patient as a fellow human being.11,12 Conversely, in taking a self-centered perspective, imagining, “What would this be like for me?” may cause personal distress and distancing from the patient.13 There is evidence that empathetic care results in less emotional distress, not only for patients, but also for doctors.13 In a qualitative study of oncologists’ involvement in end-of-life care, researchers showed that doctors who were connected to patients felt more fulfilled and had less burnout than colleagues who used distancing tactics.14

Although he was not a systematic thinker, Montaigne’s insights are full of humanity. He teaches the value of reflecting on our experience of living. The question for doctors today is, how do I remain fully human? Montaigne encourages doctors to embrace their vulnerability and engage with empathy.

References

- Hojat, M., Empathy in Health Profession Education and Primary Care. 2016, New York: Springer.

- Halpern, J., From Detached Concern to Empathy:Humanizing Medical Practice. 2001, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howick, J., V. Bizzari, and H. Dambha-Miller, Therapeutic empathy: what it is and what it isn’t. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 2018. 111(7): p. 233-236.

- Montaigne, M.d., Essays. 1958, London: Penguin Books.

- Frampton, S., When I am playing with my cat, How do I know that she is not playing with me?:Montaigne and being in touch with life. 2011, New York: Pantheon Books.

- Osler, W., Aequanimitas. 1963, New York: Nortop.

- Montgomery, K., How Doctors Think: Clinical Judgment and the Practice of Medicine. 2006, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Halpern, J., What is clinical empathy? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2003. 18(8): p. 670-674.

- Halpern, J., From idealized clinical empathy to empathic communication in medical care. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 2014. 17(2): p. 301-311.

- Shapiro, J., Perspective: Does Medical Education Promote Professional Alexithymia? A Call for Attending to the Emotions of Patients and Self in Medical Training. Academic Medicine, 2011. 86(3): p. 326-332.

- Rogers , C.R., On Becoming a Person. 1961, London: Constable.

- Coplan, A. and P. Goldie, eds. Empathy : Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. 2011, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Kearney MK, et al., Self-care of Physicians caring for Patients at the end of Life “Being Connected….A Key to Survival”. JAMA, 2009. 301: p. 1155-1164.

- Jackson, V., et al., A qualitative study of oncologists’ approaches to end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2008. 11(6): p. 893-906.

DAVID IAN JEFFREY, PhD, FRCPE, was a general practitioner for twenty years before becoming a consultant in palliative medicine. He has spent the past five years researching empathy in medical students and is the author of Exploring empathy with medical students, a book published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2019.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022

Leave a Reply