Mårten Segelmark

Lund, Sweden

More than two million people suffering from kidney failure are currently being kept alive by dialysis. But when Nils Alwall was a young doctor eighty years ago, medicine had little to offer to the patients with kidney diseases other than bed rest and tasteless diets, measures that only added new burdens to them, on top of those imposed by the uremic state. Alwall was one of the pioneers determined to change this.

Born in 1904, he came from a farming family without academic traditions. It is unclear what made him move away from home to study, first in high school and then at Lund University, but he seems to have been a motivated student and had excellent grades. As a top student at the medical faculty, he was offered an assistant teaching position in the department of physiology while also carrying on with his studies. The teaching position opened the opportunity for research, and he received a thorough training in medical chemistry, pharmacology, and physiology.

The departments of physiology and medical chemistry at Lund University were both located in a brick building outside the main campus and hospital area. These departments must have constituted a highly creative and competitive cluster where three Nobel Prize laureates spent important years in their early careers; and at least one of them (Arvid Carlsson, 2000, dopamine) had the same mentor and supervisor as Alwall, namely Gunnar Ahlgren.

After Alwall obtained his PhD in 1935, he worked in the department of medicine of the Lund University Hospital. He was a visionary man with great passion, and seeing how uremic patients suffered he felt the need to do something about it. He had some very creative ideas. He obtained access to an area in the basement of the hospital, and there, on evenings and weekends when not working in the hospital wards, he began to carry out experiments on rabbits. Instrument technicians in the department of physiology constructed the necessary devices; and he used heparin and cellophane to overcome problems with inadequate surface area and coagulation, obstacles that had hampered previous attempts to keep anuric animals alive with dialysis. Alwall was very much aware of the crucial aspects of water removal, and his machines were designed to allow negative pressure to be applied across the cellophane membrane, in order to remove excess fluid.

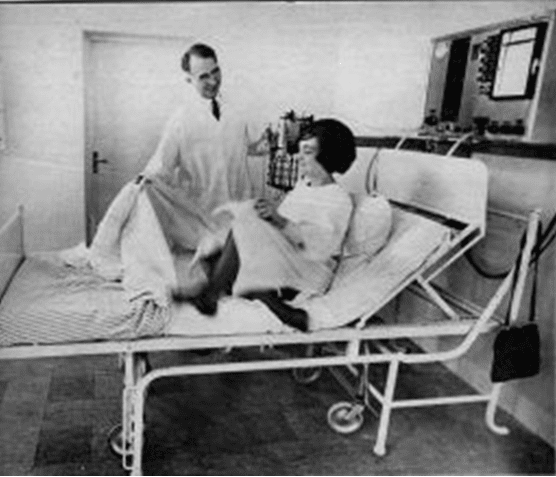

In September 1946, about three years after Willem Kolff had performed his first dialysis, Alwall treated the first ever patient with acute renal failure by combining dialysis with controlled ultrafiltration. The patient improved dramatically, and even though he died of pneumonia a few days later, it was recognized as a major success. He immediately persuaded the hospital administrators to designate a special unit for dialysis treatment, and before the end of the same year he had become head the first dialysis department in the world. The technique, the equipment, and medical care continued to improve, and Alwall’s reputation skyrocketed. In the 1950’s patients from all over Europe and the Middle East were sent to southern Sweden by airplane to receive dialysis by the “miracle man with the artificial kidney” in Lund. The dialysis unit at University Hospital in Lund has now provided seventy-two years of continuous front-end treatment for renal failure.

In order to move from treatment of acute renal injury to chronic renal replacement therapy, Alwall had to overcome two major obstacles: the problem of vascular access, and the limited capacity to treat large numbers of patients on a continuous basis. He struggled on both fronts. Beginning with his animal experiments in the early 1940s, he had designed an external arteriovenous shunt made of silicon-coated rubber and in heparinized rabbits was able to use it repeatedly for up to a week. In the late 1940s he used a similar shunt for humans, but had to abandon the technique because of clotting problems. When Belding Scribner solved the problem of clotting by making his shunts of Teflon and Silastic, Alwall was quick to adopt this technique. In 1960 he began to treat patients with end-stage renal disease using the Scribner shunt, and within two years was able to achieve long-term survival for his patients.

At a private dinner in 1961, Alwall met Holger Crafoord, the CEO of Tetra Pak AB, a company making packaging machines for the food industry. They started a lively discussion and this was the first step in the founding Gambro AB, which soon became a global supplier of “disposable kidneys” and other dialysis equipment.

When shortage of dialysis equipment was no longer a problem, the lack of other resources became the new bottleneck. Shortages of designated units with trained staff now hindered patients from getting life-saving treatments. To alleviate this, Alwall sent out his younger co-workers to start dialysis units all over the country, and invited colleagues from all over the world to come and train in his department. In order to get more resources for dialysis and other aspects of renal care, Nils engaged himself politically. He joined the ruling Social Democratic Party and became a representative in the county council. He used his contacts within the party to approach the national government and persuaded the Board of Health (Medicinalstyrelsen) to put the expansion of dialysis on their agenda. On the global level, he participated in the organization of conferences and formation of international societies, and became one of the first presidents of the International Society of Nephrology.

Alwall’s political activities, however, also gave him many enemies. Conservative professors in other disciplines disliked his unconventional ways of getting a large share of the limited resources. On the international level, his contacts with university hospitals in Prague, Warsaw, and Rostock in East Germany attracted antipathy in Western Europe and across the Atlantic. Contrasting with his political stands, he lived a traditional family life. He married into the Swedish aristocracy; his wife Ellen was a descendant of Jonas Alströmer, the founder of Swedish industrialism. Together they raised three children.

Dialysis was not Alwall’s only interest in nephrology. In 1944 he had already begun doing kidney biopsies, later developed further by his Danish friends and colleagues Iversen and Brun. Towards the end of his career he started a large screening program for the early detection of chronic kidney disease. A handful of patients who participated in that project and never developed end-stage renal disease are still followed in Lund University Hospital’s department of nephrology.

Nils Alwall was able to take his vision of treating end-stage renal disease with an artificial kidney from animal experiments to the bed-side and to worldwide implementation. To accomplish his aims he had to be able to collaborate with and seek help from instrument technicians, physicians from different specialties, hospital administrators, industrialists, international academic peers, and politicians. In doing so he became part of the creation of a new discipline, nephrology.

References

- Alwal et all. Therapeutic and diagnostic problems in severe renal failure. Berlingska boktryckeriet, Lund, Sweden, 1963

- Alwal N. Historical perspectives on the development of artificial organs. Reprint of lecture, Gambro AB, Education Department, Lund, 1985.

- Westling H. Konstgjord njure – En bok om Nils Alwall. Bokförlaget Atlantis, Stockholm, Sweden, 2000.

MARTEN SEGELMARK is a Professor and Chair of the Division of Nephrology at Lund University.

Leave a Reply