Lisa Shugoll

Asheville, North Carolina, USA

The arts have always provided a rich source of material for the type of introspection and contemplation that can deepen our ability to respond empathetically to those whose concerns and life experiences are vastly different from our own. This capacity for empathy is especially important for clinicians hoping to provide compassionate and effective care to transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. This essay discusses the trials and triumphs of transgender healthcare in the United States and explores the ways in which visual art can be used to foster therapeutic relationships between healthcare providers and their gender nonconforming patients.

It is a tumultuous time for those in our society whose physical bodies do not match their innate sense of who they are. The rise in visibility, admiration, and acceptance of transgender artists and activists has broken barriers and provided inspiration and encouragement to those who wish to openly express their identity and lead more authentic lives. Simultaneously, however, this increased visibility, coupled with transphobic legislation such as “bathroom bills” and military bans, has emboldened people who react to gender nonconformity with fear and hate. Gender nonconforming individuals are vulnerable to discrimination and violence, and are more likely than the general population to experience psychological distress including depression, substance abuse, and suicide.1 It is well documented that compassionate healthcare, including (but not limited to) gender affirming therapies, greatly reduces psychological distress and significantly improves overall well-being in transgender and gender nonconforming individuals,2 but transgender medicine is a nascent field in which best practice standards have yet to be fully established.3 In addition, “trans-experienced healthcare professionals are rare and mostly located in urban areas.”4

The number of transgender individuals in the United States is estimated at 1.4 million and rising.5 If we include gender nonconforming people in that count, the number will certainly be much higher and we can expect clinicians in all arenas of healthcare to be increasingly called upon to provide both primary and specialized care to such patients. Clinical education in this area is improving, but we must also educate ourselves about the interpersonal, emotional, and social aspects of what it means to be transgender or gender nonconforming. How can cisgender providers, who have no personal and perhaps no peripheral knowledge of the non-binary experience, attune themselves more fully to the needs of their patients? Nothing is more important than listening with open hearts and open minds to the individual and collective concerns of the gender nonconforming community. A good place to start is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), which has developed, and made available in eighteen languages, worldwide standards of care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals.6 We can also look to the arts for guidance in exploring unfamiliar aspects of the human condition. While artistic work related to the transgender experience might not yet be readily accessible in books and museums, the internet abounds with powerful work being created by transgender and gender nonbinary artists.

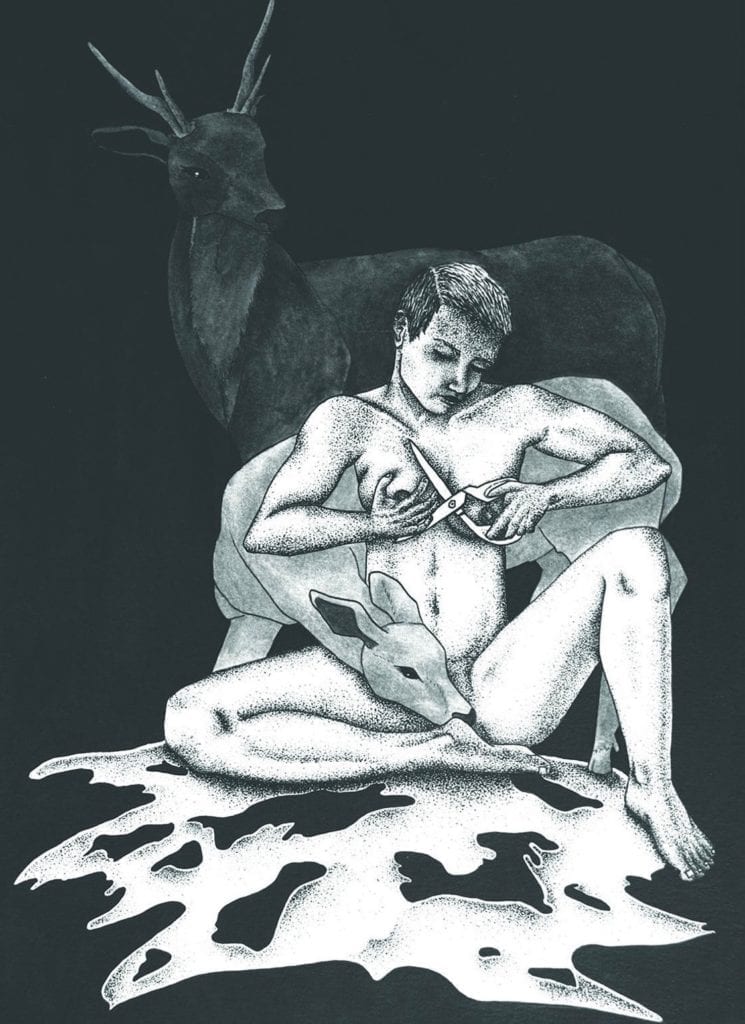

Caelin Lee, a “transmasculine, non-binary/genderqueer artist”7 based in Olympia, Washington, uses many forms of creative expression to explore the myriad aspects of human transformation. If we consider Lee’s pen and ink drawing, Crux, we may gain some insight into the body dysphoria experienced by many transgender individuals. In the drawing, a human figure uses a large pair of scissors and begins to cut off one of their8 breasts while a doe cradles the figure and a stag stands in the background. The person is sitting on what appears to be a skin or pelt that is torn around the edges and riddled with holes. The drawing gives profound visual form to the psychological distress of body dysphoria. Look carefully at the facial expression of the person in the drawing. The intense concentration and determination to complete the task at hand are evident, but in spite of the fact that they are in the process of inflicting tremendous physical pain upon themselves, this person appears serene, knowing that corporeal wounding will yield emotional healing and peace. While multiple studies have shown that gender-affirming treatment improves overall well-being for transgender people,9 it is also true that many of those people will avoid seeking proper medical care because they fear, or have already experienced, disrespectful treatment from providers.10 The title of the work, Crux, points to both the confounding problem and the most salient feature of gender dysphoria—a mismatch between a person’s outward physical appearance and their innate, internal sense of who they are.

The discarded skin lying in the foreground of the work draws the viewer’s eye. Its whiteness stands in stark contrast to the black background and throws into relief its jagged edges and multiple holes. It is as if the one to whom the skin belonged had tried many, many times to make it fit, to make it comfortable, all to no avail until, finally, the old skin is shed.

What are we to make of the doe whose body supports the person, and whose head rests in the person’s lap, concealing their genitalia? Or of the stag, which stands watchfully, perhaps protectively, in the background, barely noticeable in the darkness? Perhaps we see them as symbols of compassion and strength, representing the extraordinary courage of so many transgender people, and the kindness and support they deserve from those of us in caring professions. We may also see the doe and buck as representations of a binary system of gender that no longer works in the human world.

It has been suggested that one of the most helpful things medical care providers can do if we hope to become allies and advocates for the health of the LGBTQ+ community, is to accept that gender is a social construct and to let go of the binary system that requires each of us to be either male or female.11 In an extensive review of medical education literature related to transgender healthcare, Dubin, et. al., found “no explicit mentions of health topics specific to gender nonbinary populations,”12 yet it seems likely that these individuals may indeed face even more violence and discrimination than members of the transgender community whose appearance conforms more closely to the familiar binary. Clinicians will be hard pressed to find information in medical literature regarding the support of nonbinary individuals who desire partial transition or none at all. Only two countries worldwide recognize a “third gender” on birth certificates and legal documents,13 but the concept of a gender that is neither male nor female has long been with us. The Indian Health Service website recognizes two-spirit individuals, noting, “In most tribes they were considered neither men nor women; they occupied a distinct alternative gender status.”14 And eighteenth century missionaries visiting Tahiti noted the presence of mahus, now recognized as third gender.15 In 1902, Paul Gauguin depicted a mahu in his painting Marquesan Man in a Red Cape (also known as The Sorcerer of Hiva Oa). Contemplation of this painting and Gauguin’s related journal entry allows us to see beauty in gender diversity.

The mahu’s bright red cape is a focal point of the painting, standing out from the lush blues and greens of the surrounding scenery. The color red has many associations including passion and power, especially feminine power, given its connection to menstrual blood and fertility. Gauguin’s journal identifies this figure as a young man, “He walked before me with the suppleness of an animal and the grace of an androgyne. And I believed I saw incarnated in him, palpitating and living, all the splendor of the flora around us. From it, in him, through him was loosed and emanated a powerful perfume of beauty.”16 Gauguin portrays the mahu with white flowers tucked behind one ear and holding a small green leaf in one hand, thus depicting visually the natural splendor and beautiful perfume he describes in his journal. Can we, too, see beauty and bravery in gender diversity, rather than pathology or abnormality?

Contemplative engagement with art created by or depicting the experience of transgender or gender nonbinary people provides a safe space for exploring our own personal reactions, both positive and negative. What makes us uncomfortable? What do we find beautiful? Can we see the bravery and stand in support of it? If we find an image disturbing, can we seek to understand why? We must be willing to broaden our horizons through film, literature, and visual art, in addition to furthering our clinical education, so that we can provide safe, empathetic, and compassionate care to members of the transgender and gender nonbinary community.

References

- Mark A. Schuster, Sari L. Reisner, and Sarah E. Onorato, “Beyond Bathrooms — Meeting the Health Needs of Transgender People,” New England Journal of Medicine 375, no. 2 (July 14, 2016): 101, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1605912.

- Megan C. Stanton, Samira Ali, and Sambuddha Chaudhuri, “Individual, Social and Community-Level Predictors of Wellbeing in a US Sample of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Individuals,” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19, no. 1 (2017): 33, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1189596.

- Nicole Rosendale et al., “Acute Clinical Care for Transgender Patients: A Review,” JAMA Internal Medicine 178, no. 11 (November 1, 2018): 1535, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4179.

- Jana Eyssel et al., “Needs and Concerns of Transgender Individuals Regarding Interdisciplinary Transgender Healthcare: A Non-Clinical Online Survey,” PLOS ONE 12, no. 8 (August 28, 2017): e0183014, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183014.

- Rosendale et al., “Acute Clinical Care for Transgender Patients,” 1535.

- “WPATH World Professional Association for Transgender Health,” accessed March 2, 2019, https://www.wpath.org/.

- Caelin Lee, accessed March 1, 2019, https://www.caelinlee.com.

- In this article I have chosen to use the plural pronouns they/them preferred by many transgender and gender nonconforming individuals.

- Kevan Wylie et al., “Serving Transgender People: Clinical Care Considerations and Service Delivery Models in Transgender Health,” Lancet (London, England) 388, no. 10042 (July 23, 2016): 406, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00682-6.

- Sam Winter et al., “Transgender People: Health at the Margins of Society,” The Lancet; London 388, no. 10042 (July 23, 2016): 395, https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8.

- Megan Bass et al., “Rethinking Gender: The Nonbinary Approach,” American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 75, no. 22 (November 15, 2018): 1821, https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp180236.

- Samuel N Dubin et al., “Transgender Health Care: Improving Medical Students’ and Residents’ Training and Awareness,” Advances in Medical Education and Practice 9 (May 21, 2018): 379, https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S147183 Italics mine.

- Wylie et al., “Serving Transgender People,” 402.

- “Two Spirit | Health Resources,” Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health, accessed March 3, 2019, https://www.ihs.gov/lgbt/health/twospirit/.

- Christopher Reed, Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 21.

- Reed, 23.

LISA HIGGINS SHUGOLL holds a BSN from UNC-Chapel Hill and a PhD in Comparative Humanities from the University of Louisville. She is interested in the pedagogy of medical humanities and in the ways in which the visual and performing arts can help healthcare providers maintain their compassion and resilience.

Leave a Reply