Introduction

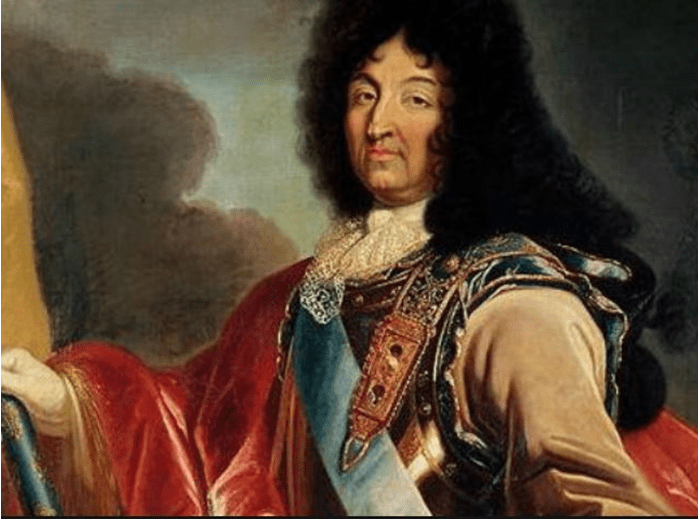

For over 300 years King Louis XIV has occupied a special place in the heart of every Frenchman. He brought glory to his country, extended its boundaries, and promoted the arts and letters so that French culture became second to none in Europe. For many decades his neighbors trembled at the sound of his armies; the mystique survives to this day; and students in France still have to study his wars, and the treaties that ended them (Aix-la-Chappelle, Nijmegen, Ryswick, and Utrecht).1

Yet the Sun King barely escaped not being conceived at all. His father, Louis XIII, disliked contact with women and had to be almost forced into his queen’s bed. But when at last a male heir was produced (1638) there was universal rejoicing. Te Deums were sung in all churches and cathedrals, for now the succession of the dynasty was ensured and the country had a dauphin, Louis Le Dieudonné—the gift of God. He turned out to be only 5 feet, 4 inches tall, but grew up strong and healthy. At nineteen he fell in love with a clever and entertaining woman but was forced to make a dynastic marriage with the dull, uneducated daughter of the King of Spain. This did not prevent him from later fathering more than a dozen illegitimate children.1

History

France in the seventeenth century was the most powerful and populous country in Europe. Its population of 21 million surpassed Russia’s (14 million) and greatly exceeded England’s five million (8.2 for the British Isles). France had the advantage of a centralized government at a time when Germany and Italy were not unified. Its lineage of kings could be traced with little interruption to Charlemagne and seemed to have reached its apogee under the Sun King.

In 1661, when Louis turned twenty-two, his chief-minister and tutor, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, died. He had spent many hours teaching Louis the “métier” of kingship and keeping him informed of everything going on in the kingdom. Accordingly, the young man now felt he knew it all. On the day after Mazarin died, he announced he was now going to rule by himself. There was to be no more chief-minister, and nothing was to be ordered or signed without his permission or command, not even a passport. He was to rule absolutely, by the grace of God. Proud of his army and conscious of his might, the Sun King would soon confront the neighboring countries, not eschewing violence or terror if deemed necessary. He went to war and annexed part of what is now Belgium, as well as Loraine and Alsace (including Strasbourg), and he also acquired from Spain territories adjacent to Switzerland and the Pyrenees. At home he tamed the potentially rebellious feudal lords by building a great palace at Versailles and making the nobles live there and enjoy life under his close surveillance.1

Medical

But like T.S. Eliot’s broad-backed hippopotamus, who seemed so firm to us but was merely flesh and blood,2 Louis XIV was heir to the same ailments as the meanest of his subjects. At eight, he came down with the dreaded smallpox. From this he survived but was left with his face badly marked by disease. Later he had the measles. At sixteen he was “abruptly introduced to sex”, had his “first experience with human flesh,” and some girl of uncertain social standing gave him “a case of gonorrhea that caused his doctors to worry about loss of fertility.”1

At twenty he had a fever, probably typhoid. Six physicians bled him vigorously, attacked him with enemas, prescribed emetics to clear out his stomach, and gave him a tea that “sent him to the pot for fourteen to fifteen times in a day.”1 When he got well they patted themselves on the shoulder and attributed his recovery to “the nine good bleedings” they had given him. In reality, he recovered despite their medical attention.

During his adult life, Louis had a succession of physicians, all of the same ilk (Vallot, L’Aquin, Fagon3). All were wedded to the strange therapeutic doctrines of the time, assaulting him for the rest of his life with regular bleedings, enemas, and purgatives. It seems that he had a bleeding and a colonic cleanse at least once a month, and some have estimated he received over 2000 enemas in his life. During the first part of his reign he had various minor illnesses—some real, such as colds, dizzy spells, periods of deafness, perhaps malaria—and some more hypochondrial. He may also have been plagued by various parasite infestations, ascaris, trichinella, and fasciola hepatica.4 At age forty-five he fell off a horse and dislocated his shoulder but recovered well. He then developed a form of rheumatism. His teeth became bad and were pulled brutally, in part presumably to help his rheumatism but caused a connecting fistula between his mouth and his nose. It caused liquids to spray out of his mouth into the nose “like a spring,” gave him a bad taste in his mouth and a bad smell in his breath, and required cauterization of the passage, which would have been done at the time without anesthesia.1

By 1668 he had become overtly obese, began having attacks of gout, and, in 1686, developed a painful anal fistula, inflamed and filled with pus. He could no longer ride a horse, was confined to bed, and was discharging unpleasant intestinal contents into the environment. Surgery became necessary. The chief surgeon honed his skills by operating on as many people he could find in the hospitals of Paris and thus became highly skilled in performing this procedure. The operation on the king went well, he bore the pain bravely, and three surgeons each received 80,000 to 150,000 livres, but the four apothecaries in attendance each received only a paltry 12,000.1

As Louis aged, his gout became more frequent. He could no longer eat the huge meals he had become accustomed to. His health was deteriorating despite more frequent and aggressive bleedings, enemas, and purgatives. By sixty-six his health had become poor, spirits low, and his teeth almost all gone. He was still able to attend council meetings, listen to concerts, and attend hunts in his carriage. In August 1715 he developed pain in his leg. The doctors thought he had sciatica. Then a black spot appeared on his leg. The doctors tried their usual remedies but to no avail. The gangrene spread almost to the thigh.1 He died four days before his seventy-seventh birthday, having worn the crown of France longer than any other European monarch.

Legacy

The first two wars brought Louis power and glory. Later, he was not so successful. His last two wars (against the League of Augsburg and the War of Succession of Spain) left France impoverished and drained. His persecution of the Protestants, and the revocation of the privileges accrued from the Edict of Nantes, was counterproductive. It caused thousands of educated professionals and skilled tradesmen to flee to France’s enemies, devastated the economy, and provoked the creation of an anti-Catholic alliance of the great powers of Europe. His actions fit best in Barbara Tuchman’s definition of folly, of leaders making decisions detrimental to the interest of their country when better options are clearly available.5 “Shorn of his tremendous curled peruke, high heels and ermine, the Sun King was a man subject to misjudgment, error, and impulse… He exhausted France’s economic and human resources by his ceaseless wars and their cost in national debt, casual ties, famine, and disease.”5 Weakened and insolvent, France was shaken within a few decades by the dreadful events of the French Revolution.

References

- Lewis XIV, by John B Wolf, W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1968

- S. Eliot, Selected Poems, Harbrace Paperbound Library, New York, p. 40

- Le Roy, Journal of the Health of Louis XIV. Referenced in New York Times 1862,27 July

- Alexander Dorozynsky. Parasites likely to have plagued Louis XIV, BMJ, 1998,1315:1477

- Barbara W. Tuchman, The March of Folly, Abacus Books, 1984, p. 21-27

Leave a Reply