Paul Dakin

North London, United Kingdom

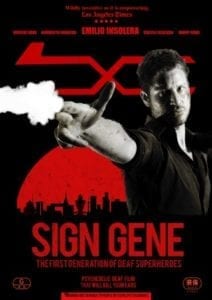

directed by Emilio Insolera. Image published with permission.

If the superhero genre really is “about transformation, about identity, about difference,”1 then the description can readily be applied to Sign Gene, the world’s first deaf superhero film. Written and directed by Emilio Insolera, who was born deaf to deaf parents, this “unlikely cult classic”2 is a sci-fi thriller in which deaf people have superpowers.

The central idea of the film is that specific genetic mutations have given rise to both loss of hearing and to abnormally powerful abilities. This is demonstrated in the opening scene when a man seated at a desk uses the American Sign Language (ASL) handshape for “paper” and a sheet flies into his hand. The lead character Tom Clerc—played by Insolera—is introduced with a nonchalant flick of the thumb that produces a flame to light an invisible cigarette. However, it quickly becomes apparent that these powers can be dangerous—an assassin points four fingers at a victim and bullets materialize to fly into his target.

In response to the knowledge that powerful deaf mutants exist, the US Government establishes the Quinpar agency to monitor and control their activity. All the agents are either deaf or children of deaf adults (CODAs), who receive training at a special school in New York to develop their superpowers. The name of the agency links the special abilities with the practice of signing by referring to the “five parameters” i.e. “Quinpar” of sign language—handshape, movement, location, orientation, and non-manual signals.

Quinpar agents Tom Clerc and his partner Ken are sent to investigate a series of shootings in Osaka, Japan, rendered strangely unique by the lack of bullets found in the victims. These include the murder of a senator’s daughter. Tom discovers that a local gangster, Tatsumi Fuwa, intends to obtain and purify the DNA sequences that contain “sign genes,” replicate them in a serum and inject them into hearing villains, thus transforming them into an army with superpowers. Fuwa had been badly mistreated at home because of his deafness, and has developed his own skills that led him to control a vast criminal enterprise. The name of Fuwa’s corporation that isolates and manufactures the serum is 1.8.8.0. This is one of several references to Deaf history in the film, as 1880 is the year of the Milan congress that outlawed the use of sign language in deaf education in favor of teaching oral speech. Fuwa has obtained specimens containing the “sign gene” with help from Tom’s crazed brother, who wants to eliminate signers and signing. Tom learns that the senator’s daughter, who also possessed deaf superpowers, had accessed Fuwa’s company information and passed it to an associate with the aim of exposing the plot. Both were assassinated with “four finger bullets.”

Tom and Ken encounter Fuwa’s gang and discover that the criminals are too powerful to defeat. The agents are sent for training to a fragile looking elderly lady who is in fact a master of the “sign gene” arts. She helps the agents expand and develop their potential well beyond their expectations. Tom and Ken pursue the mobsters once more, and during the ensuing battle signed handshapes conjure weaponry out of the air, including samurai swords, electrical charges, light, bullets, and imaginary yet powerfully painful fists and feet. Fuwa’s right hand man is captured by a rope brought into being through Tom’s newly emerged genetic power. The denouement takes place when the agents track Fuwa to a forest, erupting into another awesome demonstration of “sign gene” powers.

that produces a flame to light an invisible cigarette.

Image Published with permission.

The one hour, low budget film is exciting and interesting. It employs tropes typical of the superhero genre, including the pair of mildly rebellious good guy buddies, and the visit to an unlikely mentor who surprises and schools with her mysterious powers. As superheroes are supposed to “have baggage,”3 the lead character temporarily loses his identity and memory, and there is an evil family member, who in this case happens to have no eyelids.

Wanting to change the historically grounded complaint that “deaf parts have gone to hearing actors,”4 Insolera ensured that all the cast and crew were either deaf or CODAs. The film is a “global mix of ways to communicate”5 with six languages used—American, Italian, and Japanese Sign Languages, alongside their verbal equivalents. Elements of Deaf history are cleverly inserted into the plot, especially through the device of characters being the descendants of historical heroes renowned within Deaf culture. Tom Clerc, for instance, is portrayed as the fictional descendant of Laurent Clerc, the eighteenth century French educator who has been called the “apostle of the Deaf in America.” William Stokoe, who codified ASL as a language is referenced, as well as events such as the “Deaf President Now” protests at Gallaudet, an American university for those who are deaf and hard-of-hearing, in the 1980s.

Sign Gene is a futuristic film that makes good use of locations, with a visual style that includes fast-paced stroboscopic screen action6 and video effects simulating the grainy, scratchy appearance of vintage film stock.7 There is much use of fast forward, particularly in the action sequences, with some scenes jumping quickly from one to another and back again, which may leave the viewer feeling confused. This may be a visual attempt to imply the disorientation experienced by deaf people in an aural world, a parallel to the sound design described by Insolera as mimicking “barriers of communication” and being a “metaphor for interruptions in communication we routinely experience.”8

out of the air. Image published with permission.

Concerned that “deaf characters on TV and in movies are being seen through the eyes of hearing people,”9 Insolera wants “to show deaf people in a different light and not as the stereotypical victim.”10 Believing he is “lucky to be deaf because that separated me from those communities that . . . can distract you from your goals,” Insolera prefers to ditch the word “deaf,” with its auditory implications, in favor of the phrase “visual speaking.” This fits with Garland Thomson’s assertion that deafness is not “a disabling condition in a community that communicates by signing as well as speaking”11 and allows the perception of deafness to shift from “a form of pathology to a form of ethnicity.”12 Enthused by the potential of sign language, Insolera states, “If I could have one superpower myself, it would be the power to make everyone understand and be able to express visual signs.”13

There is a long though not extensive history of deaf superheroes in comics,14 but few are shown to use sign language. Sign Gene, however, is the first film to link deafness with superpowers. In particular, a strong connection is made between the ability to sign and the possession of superhuman abilities. The concept of genetic variation giving rise to both hearing loss and supernormal abilities has also been used in an on-line graphic novel, The Prophecy in Blue. This portrays a dystopian world in which The Hearing Front wants to outlaw sign language and destroy the super-powerful deaf mutants.15 Sign Gene was filmed four years before the novel’s publication and can claim to have expressed this interesting link first.16 Alaniz points out that there are risks inherent in creating “disabled” characters that are “supranormal,” as this may lead to misrepresentation through their exaggerated abilities.17 This risk may be discounted in Sign Gene, as the genetic prowess is shown in the context of characters who display backgrounds, features, and limitations that resonate with many people, regardless of whether they are deaf or hearing. Rather I would suggest that Sign Gene, described as “wildly inventive as it is empowering,”18 emphasizes the new understanding that has emerged from Gallaudet in the last few years, in which deafness is seen as an evolutionary divergence that carries advantages for both the hearing majority and the non-hearing community.19

End Notes

- Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester, The Superhero Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013).

- www.imdb.com/title/tt4715060/

- Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester, The Superhero Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013).

- https://www.tokypweekender.com/2018/11/sign-gene-emilio-insolera-on-creating-the worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film

- (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2018/11/13/films/deaf-filmmaker-emilio-insolera-on -creating-the-worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film/

- www.imdb.com/title/tt4715060/

- Michael Rechtshafen (Los Angeles Times) April 12, 2018.

- (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2018/11/13/films/deaf-filmmaker-emilio-insolera-on -creating-the-worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film/

- (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2018/11/13/films/deaf-filmmaker-emilio-insolera-on -creating-the-worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film/

- https://www.tokypweekender.com/2018/11/sign-gene-emilio-insolera-on-creating-the worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film

- Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

- Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

- https://www.tokypweekender.com/2018/11/sign-gene-emilio-insolera-on-creating-the worlds-first-deaf-superhero-film

- PK Dakin, “Deaf characters in comics: the evolution of the deaf superhero” (awaiting publication)

- Z Naqvi, J Correa, and CJ Hurtt. Signs and Voices Series 1 – Prophecy in Blue, Episode 1 On-line: Deaf Power Publishing House: 2012.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Claf_2B2lJc

- Jose Alaniz, Death, disability and the superhero: The silver age and beyond (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

- Michael Rechtshafen (Los Angeles Times) April 12, 2018.

- H-Dirksen L Baumann and Joseph J Murray, Deaf Gain: Raising the stakes for human diversity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

PAUL DAKIN is a retired General Practitioner and postgraduate Trainer from North London. He has a Master’s degree in Literature and Medicine and is the former Secretary of the Association for Medical Humanities. His research interest is the representation of deafness and deaf people.

Leave a Reply