James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, USA

|

| George Gershwin, 28 March 1937. Photograph by Carl Van Vetchen. 1937. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division. |

On the morning of Monday July 12, 1937, New Yorkers who had just suffered through five days of a heat wave that left thirty-eight people dead, awoke to read on the front page of the New York Times about the death of George Gershwin, a native son of their city. The heading of the article ran: “George Gershwin, Composer, Is Dead: Master of Jazz Succumbs in Hollywood at 38 After Operation for Brain Tumor.” Although rumors that Gershwin might be seriously ill had appeared in a Hollywood gossip column written by Walter Winchell, New Yorkers and the public at large had little preparation for his untimely and tragic death. At the time of his death, Gershwin had written music for over 550 popular songs that had appeared in forty-four Broadway shows, forty-nine films, and had composed two operas, notably his final masterpiece Porgy and Bess. In addition, he had composed classical works and ballet scores including: Rhapsody in Blue, Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra, Second Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra, An American in Paris, and Three Preludes for Solo Piano.

The details of his final illness have been reviewed by several authors in the medical literature and an account of the symptoms the composer suffered during the final years of his life can be found in many biographies.1-6 While the accounts and recollections of the composer’s friends, relatives, and colleagues differ in certain details as to the appearance of symptoms and the medical care he received, a generally consistent narrative of his illness emerges from these sources. A review of literature both medical and biographical provides insight into the symptoms he suffered, the medical care he received, the type of tumor that took his life, and inferences about the neurological basis of musicality in the central nervous system.

On the evenings of February 10 and 11, 1937 George Gershwin appeared with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in an all-Gershwin program. Biographies of the composer indicate that he looked forward to this concert as an opportunity to advance interest in a west coast production of his opera Porgy and Bess, which had its east coast premiere two years earlier. During the second of the two concerts, while performing his Piano Concerto in F, he seemed to lose consciousness momentarily and missed a few bars of his piano solo. With the aid of the conductor Alexander Smallens, they were able to complete the performance without interruption. Reviews of the concert did not mention the episode and it may not have been noticed by the audience. His friend Oscar Levant, who was in the audience, went back stage and asked him what happened: “Did I make you nervous or did you think Horowitz was in the audience?”7 Gershwin revealed that he had experienced a sensation of smelling burnt rubber. While rehearsing with the orchestra the afternoon before the concert, he had been observed at one point to sway and almost fall from the podium.

Two months later, in April, a similar episode occurred while he was seated in a barber chair. Over the next several weeks Gershwin experienced an ever-alarming progression of symptoms that included a marked personality change, severe headaches with photophobia, dizziness, lethargy, progressive clumsiness in everyday tasks, and difficulty playing the piano.

Gershwin, advised by well-meaning friends that his symptoms were psychosomatic, consulted a psychoanalyst in Los Angeles, Ernest Simmel. Simmel believed that they had an organic basis and referred him to an internist, Gabriel Segall.

By this time, the symptoms of headache, dizziness, and disagreeable, foul-smelling olfactory sensations were occurring almost daily. On June 20, Gershwin was seen by a neurologist, Eugene Siskind, in conjunction with Dr. Segall. A complete neurological examination, including an examination of the optic nerves, was normal except for an impaired sense of smell in the right nostril. A record of Dr. Siskind’s complete neurologic examination can be found in the medical literature.8 Gershwin was hospitalized at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital between June 23 to June 26 for additional studies, a Wasserman test, blood work, X-rays of the skull, and examination of the eye grounds, which were all normal. A lumbar puncture was recommended but Gershwin refused when he was advised the test might cause headaches. Even at this stage the conclusion in the hospital record was that his symptoms were hysterical.

He returned home with assistance from a male nurse and though briefly he seemed improved, his condition continued to deteriorate. His motor coordination worsened, he stumbled on stairs, dropped objects, spilled liquids, and had trouble eating and playing the piano. He was being given phenobarbital for his headaches and grew listless. He experienced two epileptic episodes known as automatisms. In one instance, while being driven to a psychoanalytic appointment, he opened the car door and attempted to eject the driver. In a second episode, he had received a box of chocolates and proceeded to use them as a body ointment. He had no recollection of these episodes and could not explain his behavior.9

On the morning of July 9 he was able to play the piano, but by five o’clock in the afternoon he became drowsy and lapsed into a coma. He was readmitted to the hospital and seen by a neurosurgeon, Carl Rand, who found him in a deep coma with papilledema, right-side facial weakness, and flaccidity of the right arm and leg. A spinal tap was performed, revealing an elevated opening pressure and elevated spinal fluid protein. A brain tumor was suspected and immediate surgical intervention preceded by ventriculography was recommended. At the same time, the world-famous neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing was contacted. Having recently retired, Cushing recommended his former student, the then famous neurosurgeon Walter Dandy. At the time Dandy was on vacation aboard a yacht on the Chesapeake Bay. Through a contact in the White House, the Coast Guard was dispatched to bring Dandy to shore, followed by a motorcycle police escort to the Cumberland, Maryland airport. There a private plane took him to the Newark Airport for a scheduled flight to the west coast. Simultaneously Dr. Howard C. Naffziger, a Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of California, was located while he was vacationing at Lake Tahoe. Naffziger was flown to California and arrived at the hospital at 9:30 that evening. In consultation with Dr. Rand, who performed the operation, neurosurgery was begun. As William Hyland points out in his biography of Gershwin: “These eminent doctors’ services were by no means free. Dandy charged $1000 for his telephone consultation; Dr. Naffziger charged $2,500 for his consultation at the operation. The actual operation was performed by Doctor Carl Rand, whose fee was 12,500 dollars.”10

|

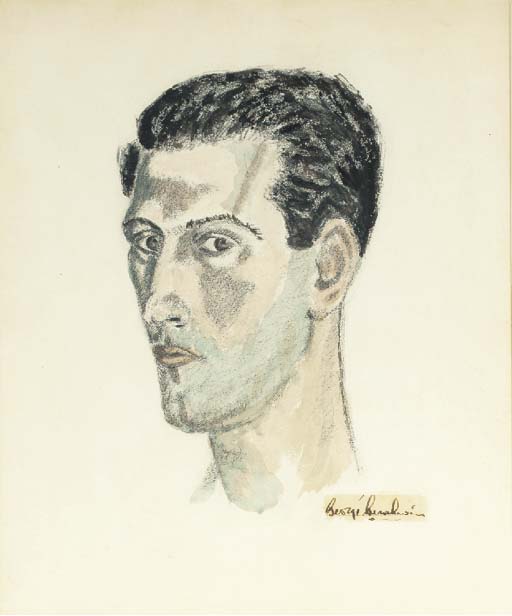

| Self-Portait. George Gershwin. 1937. Christie’s, Samuel and Frances Goldwyn collection. |

An initial ventriculogram revealed findings consistent with a tumor in the right temporal lobe. The ventriculogram showed both ventricles pushed far to the left. The left ventricle was normal in size and shape. The right ventricle was small; the temporal horn was missing. A diagnosis of a right temporal lobe tumor was established. A right sided osteoplastic flap initially revealed a cyst tumor with a mural nodule that extended deeply into the brain tissue. The cyst and nodule were removed with an electrical loop and the tumor treated with fulguration. The operation lasted five hours. Post-operatively severe hyperthermia ensued, and Gershwin died without regaining consciousness at 10:35 on the morning of July 11, 1937.11 The microscopic examination of the cystic glioma partially removed from the temporal lobe revealed a spongioblastoma multiforme, or in updated nomenclature, a malignant glioblastoma.

A paper published in 1979 in the American Journal of Pathology by pathologist Louis Carp — “George Gershwin – Illustrious American Composer: His Fatal Glioblastoma” — has been a standard reference for the type of brain tumor that caused Gershwin’s demise.12 An editor’s note at the end of the paper indicates that Dr. Carp died before the publication of the article, which was intended for a book he was preparing on well-known composers who had died at a young age. The article contains the pathology report by Dr. Isaac Yale Olch from Cedars of Lebanon Hospital as well as two microphotographs provided by Dr. Nathan B. Friedman. It is not entirely clear from this article whether the microphotographs demonstrated the type of tumor Gershwin had. A more recent article (2001) on Gershwin’s tumor by Gregory D. Sloop from the Department of Pathology of the Louisiana State University of Medicine, reproduces a similar microphotograph labeled as Gershwin’s tumor and provided by Dr. Nathan B. Friedman of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.13 It is Dr. Sloop’s belief that the tumor was a pilocytic astrocytoma. He reviews the natural history of this tumor, which is often associated with a slow rate of progression and long history of symptoms over many years.

This conclusion has relevance to Gershwin’s medical history and his unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms. Beginning at the age of twenty-three, he had suffered from recurring attacks of abdominal discomfort and severe constipation. There is controversy in the literature about when his olfactory hallucinations began. The July 1937 concert described above is usually taken as the onset of his olfactory hallucinations but a biography written by Joan Peyser reports that these symptoms began in 1934.14 This information came from the recollections of Mitch Miller, an oboist and friend of Gershwin’s, when they were on an extended concert tour. In an earlier paper, the neurosurgeon Bengt Ljunggren suggested that the gastrointestinal symptoms Gershwin had experienced for many years may have been a manifestation of a slowly infiltrating astrocytoma in the temporal lobe and autonomic symptoms as a result of epileptic activity.15

Gershwin had consulted many doctors for his gastrointestinal complaints with little relief. In 1934 he began psychoanalysis (initially five times a week) with the famous Russian psychiatrist Gregory Zilboorg (1890 – 1959). He underwent psychoanalysis for a period of fifteen months and had a very favorable outlook on his therapy, seeing it as part of his personal growth. Gershwin and Zilboorg took a trip together to Mexico toward the end of 1935 in an effort to reduce the stress he was under. It was Zilboorg whom Gershwin would call after the episode in the barbershop, and after the composer’s death stated that he had advised him that his symptoms were organic.

Several medical authors have looked at the care Gershwin received and asked: what could have been done differently? Focusing on the symptoms Gershwin experienced in February 1937, in retrospect these symptoms would have prompted a thorough neurologic evaluation. Given today’s diagnostic armamentarium it is likely that the tumor would have been diagnosed. It is interesting to review his treatment in light of the resources that were available to neurologists in 1937.

Three diagnostic tests entering clinical practice in 1937 might have facilitated a diagnosis. Pneumoencephalography was a diagnostic test that consisted of performing a spinal tap, withdrawing fluid, and injecting air to visualize the cerebral ventricles by X-ray examination of the skull. This study ironically had been introduced as early as 1919 by Walter Dandy. As Gershwin had refused a lumbar puncture, it is unlikely he would have accepted this procedure, which often causes severe headaches. “Percutaneous carotid angiography was introduced in Boston by Loman and Myerson in 1936, but published reports of its effectiveness did not appear until after World War II.”16 Finally, electroencephalography might have revealed the organic nature of his olfactory symptoms as being related to epileptic activity. The test was first introduced in 1929 by Hans Berger in Germany, and became generally accepted after a series of articles by Gibbs, Lennox, and Davis out of Boston published between 1934 and 1937. It is not certain when the test entered clinical practice in California.

Neurosurgery came into being as a new discipline during the early decades of the twentieth century. Harvey Cushing (1869 – 1939) was a pioneer in the treatment of brain tumors and Michael Bliss’ 2004 biography of the surgeon provides insight into the dismal prognosis and outcome from surgical intervention for patients such as Gershwin.17 At least one author believes that by the time Gershwin was operated on, brainstem herniation and hemorrhage had already occurred and recovery was impossible.18 Walter Dandy wrote Dr. Segall in August 1937 after reviewing the pathology report that: “There are not many tumors that have uncinate attacks that are removable, and it would be my impression that the tumor in large part may have been extirpated … it would have recurred very quickly since the whole thing fulminated so suddenly at the onset. I think the outcome is much the best for himself, for a man as brilliant as he with a recurring tumor would have been terrible; it would have been a slow death.”19

Writing in a symposium devoted to neurological disorders in famous artists, Edwin Ruiz and Patricia Montanes see Gershwin’s remarkable continued musical proficiency, present until the last months of his life, as a manifestation of preserved musical competence in the left cerebral hemisphere.20 They cite literature demonstrating that in musicians, musical processing predominates in the left hemisphere. Gershwin’s final six months of life were marked by declining productivity and make sad reading. The once handsome, charming man, a good dancer, an accomplished and largely self-taught artist who was athletic (a good golfer and tennis player), became irritable, quarrelsome, and clumsy. While he had never failed to meet a contract, he had to endure the humiliation of being fired by Samuel Goldwyn for whom he was writing the music for the film Goldwyn Follies. Gershwin, who with his brother and lyricist had come to Hollywood in 1936 to write for the movies, was disillusioned with the film industry and wanted to return to New York and write serious music. His proposal of marriage to Pauline Goddard, who was then married to Charlie Chaplin and with whom he was deeply in love, had been rejected. He was beginning to lose his usual self-confidence and worried that he was going bald. He had purchased an “Evan’s Vacuum Cap” — a metal cap and suction device — advertised as being effective in treating baldness, which he even tried using to treat his headaches. These facts and his earlier history of unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms that were presumed to be psychosomatic led his friends and relatives to discount them. Feeling correctly that he was seriously ill and failing must have been overwhelmingly painful.

“Love is Here to Stay” was the last musical composition that George and Ira Gershwin completed before his death. Ira, as a tribute to his brother, wrote out the lyrics after his brother’s death and the music with Oscar Levant, who had heard Gershwin play the song before he died. The haunting refrain: “In time the Rockies may crumble / Gibralter may tumble / There’re only made of clay / But our love is here to stay” perhaps was meant to capture the bond that existed between the two brothers.

References

- Fabricant, Noah D. George Gershwin’s Fatal Headache. The Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Monthly. 1958, 37 (May): 332-334.

- Ljunggren B. The Case of George Gershwin. Neurosurgery 1982:10:733-736.

- Silverstein, A. The Brain Tumor of George Gershwin and the Legs of Cole Porter. Seminars in Neurology. 1999: 19 (Supplement 1): 3-9.

- Howard Pollack, George Gershwin: His Life and Work, University of California Press, 2006.

- Walter Rimler, George Gershwin: An Intimate Portrait, University of Illinois Press,2009

- William G. Hyland. George Gershwin: A New Biography, Praeger, Westport, CT 2003

- Walter Rimler, ibid, p. 141

- Fabricant, Noah D. ibid, p. 333

- Howard Pollack ibid p. 213

- William G Hyland ibid p.207, Fn.54.

- Gasenzer, E and Neugebauer, EAM. George Gershwin: A case of new ways in neurosurgery as well as in the history of western music. Acta Neurochir. 2015 156: 1251-1258

- Carp, Louis. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1979: 3 (October): 473-478.

- Sloop, GD. What caused George Gershwin’s untimely death? Journal of Medical Biography. 2001: 9 (December): 28-30 2001.

- Peyser, J. The Memory of All That. New York Simon and Schuster, 1993: 262-297.

- Ljunggren B ibid.

- Silverstein, Allen. Neurologic History of George Gershwin. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: 63 (May): 239-241.

- Michael Bliss. Harvey Cushing: A Life in Surgery, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Takahiro Mezaki. George Gershwin’s death and Duret haemorrhage, The Lancet. 2017: 390:646

- Green, Rob J.M and Marmaduke-Dandy, Mary Ellen. George Gershwin and his brain tumor – the continuing story. Acta Neurochir:2005: 157: 1389-1390

- Ruiz, Edwin and Montanes, P. Music and the Brain: Gershwin and Sheblin. Neurologic Disorgers of Famous Artists, Neurol Neurosci. 2005, vol. 19, pp 172-178 Basel Karger

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, M.D. is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply