There must be few people in the world who can locate with confidence Northern or Southern Rhodesia on a map of Africa. Yet these countries still exist, only the names have changed. Nor would the man who founded them win a contemporary popularity contest. In fact, his statue at the University of Cape Town was recently boarded up and the students want it torn down. For he was an imperialist, a man who paved the road to apartheid, who believed the British were the master race and hoped to expand their domination from Cape to Cairo.

His story is not one of rags to riches, for he was the son of a middle-class clergyman in Hertfordshire. But in South Africa Cecil John Rhodes acquired diamond after diamond, mine after mine—mines of diamonds and mines of gold. By 1891 he owned ninety percent of the world’s production of diamonds. He had a large stake in the Transvaal gold mines. His companies had almost a monopoly over the world diamond trade, and the De Beers company remains a living testimony of his wealth and power. He became prime minister of the Cape Colony; received a charter from Queen Victoria to extend British control northward; and founded two countries, Zimbabwe and Zambia, that until relatively recently bore his name.

For a long time it was believed he had tuberculosis in his youth and died from a ruptured aortic aneurysm in middle age. But in 1965 a consulting physician from Bulawayo in South Africa thought otherwise.1,2 So we must go back to 1869, when Mrs. Rhodes took her sixteen-year old thin and sickly-looking boy to the doctor. It had been noted that “fatigue no longer blanched his lips-it turned them livid, and exertion was followed by continually by alarming faintness.” Was there something wrong with his lungs? Could it be tuberculosis? The good doctor exercised his stethoscope and pronounced the lungs sound. But there was a problem with the boy’s heart. It was “not actually diseased” but “seriously overtaxed, laboring quite inadequately to meet the demands of his rapid growth.” So it was decided in 1870 to send the boy to a better climate in Africa, to work with his brother on a cotton farm. The rest is history: he became one of the richest and most powerful men in the world.

In South Africa Rhodes continued to periodically have these attacks when he would turn livid. He had a “serious heart attack” in 1877; another in 1895; and another in 1897, when he nearly fell off a horse. In 1897, while on holiday, he fell ill with malaria complicated by heart failure. As his heart was palpitating, a doctor prescribed digitalis, perhaps for atrial fibrillation. It is noted that Rhodes never smoked before dinner, but that after dinner he lit up one of his cigarettes specially imported from Cairo and then smoked one after another. He drank to excess and in his last few years became grossly overweight, his body thickened, his face plethoric. By 1900 he was obese, cyanosed, edematous, and looking far older than his age.1

In 1901 the palpitations subsided, but he developed chest pain. He became very short of breath, orthopneic, in gross congestive heart failure. A hole was knocked in the wall of his bedroom to allow through a breeze.1 His ascites was tapped several times and small metallic Southey’s tubes were inserted in his legs to drain off the edema. He died in March 1902. Autopsy showed venous and pulmonary congestion, and an enormously thickened pericardium adherent to the heart. There was no healed tuberculosis and no aneurysm of the aorta. The heart was not opened. The cause of death was given as heart failure.

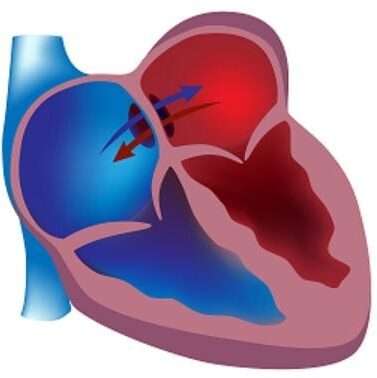

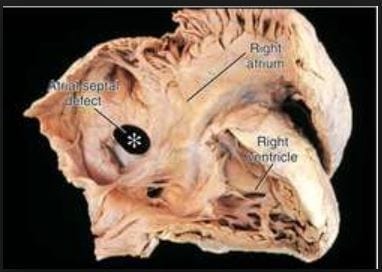

An analysis of the clinical course, with episodes of syncope and cyanosis, and then eventual permanent cyanosis suggestive of a right to left shunt has led to the suggestion that Cecil Rhodes had suffered all his life from a form of congenital heart disease, most likely an atrial septal defect. Such defects require no treatment if small, but the consensus is that large defects should be closed if possible, to prevent the later onset of heart failure, as appears to have been the case with Cecil Rhodes.

References

- Shee, JC. The ill health and mortal sickness of Cecil John Rhodes. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1965; 11: 89 (no. 4, April).

- From Other Pages. JAMA. 1966; 195: 101 (February 7)

Leave a Reply