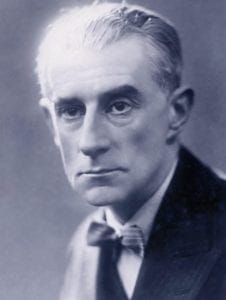

The French composer Maurice Ravel appears to have suffered from a localized neurological disease that spared higher brain functions but interfered with the basic activities of living. In neurological parlance this translates itself into loss of the ability to speak (aphasia), write (agraphia), read (alexia), or carry out complex brain directed movements or tasks (apraxia). To this may be added the “ugly word”1 amusia – loss of music. By contrast, memory, judgment, and the ability to evaluate art or feel emotion remained intact, though increasingly difficult to express verbally.1

Ravel was one of the most popular composers of his time, author of Bolero and many other well known compositions. Born in 1875, he has been described as a private person with a compulsive personality, fastidious, a perfectionist, and in his youth excessively dependent on his family, especially on his mother.1 He had a car accident in Paris in 1932; but although minor trauma may accelerate the progression of brain disease, this was generally not believed to have played a significant role in his case.

Ravel’s difficulties began in 1927, ten years before his death, when he began to make blunders at concerts, losing his place while playing or jumping from one part of the music to the wrong one. In 1929 he reportedly flew into a rage because he could not find the right word he was seeking. By 1933 he was getting worse. At one time, while trying to skim a pebble on the sea, he missed and struck his friend in the face. Writing and speaking became difficult. No longer able to play the piano, he complained he had “lost his music,” and no longer could read or use musical signs. By 1936 he even lost the ability to write his own name. Yet higher brain functions remained unimpaired and he was even able to go into society.

During his illness he was under the care of the famous neurologist Théophile Alajouanine, who later published a detailed report of the course of his disease. Several neurosurgeons were approached but thought he had a degenerative disease and did not recommend surgical treatment. Eventually Clovis Vincent, a well-known Paris neurosurgeon, operated in order to rule out tumor, but found no significant abnormality. There was a short-lived improvement but by the end of December 1937 Maurice Ravel lapsed into a coma and died.1

Tomes have been written about Ravel’s illness, and there has been much speculation about the diagnosis. Degenerative diseases of the brain are notoriously difficult to diagnose with any degree of precision, even by brain biopsy, and in a more vulgar setting have been characterized as “brain rot.” To the more traditional diagnoses of Alzheimer’s and Pick’s diseases, modern neurology has added vascular dementia and several other newly recognized entities, but these are generally diffuse diseases with early onset of dementia. One proposed diagnosis has been based on a series reported in 1987 as “primary progressive aphasia without dementia,” in which a localized or focal degeneration affected the deeper structures of the brain, the so-called perisylvian region.2 This remains a plausible diagnosis, but as no autopsy was done it appears that the precise cause of Ravel’s illness will never be known.

References.

- Henson RA. Maurice Ravel’s illness: a tragedy of lost creativity. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296(6636):1585-8.

- Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia – differentiation from Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1987;22:533.