Vincent P. de Luise

New Haven, Connecticut, USA

|

The health benefits of fruits and vegetables are a long-standing and verified aspect of nutrition science. One of those fruits, the apple, has a particularly interesting, albeit circuitous, history as a healthy foodstuff.

The well-known aphorism “An apple a day keeps the doctor away” is based on a Welsh verse from Pembrokeshire dating back to the 1830s: “Eat an apple on going to bed and you’ll keep the doctor from earning his bread.” Elizabeth Wright, in her 1913 book Rustic Speech and Folklore, recorded a version from Devon as the first documentation of the modern expression: “Ait a happle avore gwain to bed, An’ you’ll make the doctor beg his bread,” or as the more popular version runs: “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”1

Folk tales often have a kernel of truth in them. Does an apple a day really “keep the doctor away”? What is in an apple to make a person healthy enough for this to be true?

|

|

| Fig.1 Madonna and Child Hans Memling, 1490 ©Art Institute of Chicago |

Apples may be good for us, but it was not only apples or their medicinal properties that were being extolled when the phrase was coined, and it was not all “good” for the apple in days of yore. In Old English the word “apple” was used to describe any round fruit that grew on a tree. This is corroborated by the Linnaean taxonomy for apple fruit and the tree from which it stems, which are in the genus Malus. The words mālum and melus, both derived from the Greek melon, are second declension Latin nouns which translate as “apple,” but they could also refer to any “fruit.”

However, the word mălum is also a Latin adjective (mălus, măla, mălum) meaning “evil” or “bad,” which created some confusion and trouble, as the apple actually had a somewhat “bad” beginning. In the Book of Genesis, Adam and Eve pluck a forbidden fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden, which leads to their expulsion from the Garden. It has been debated as to what kind of fruit or vegetable was on that tree: apples, figs, grapes, citrons, olives, apricots, and pomegranates have all been proposed,7 and ambiguity remained as late as 1611 in the King James version of the Bible, where it was still referred to simply as a “fruit.” However, by the late 1400s, the apple had begun to appear in devotional art of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, where the apple represented the fruit of the resurrection (Fig.1).

|

|

| Fig.2 The Fall from Grace, Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1535, ©Capella Sistina, Vatican City, Rome |

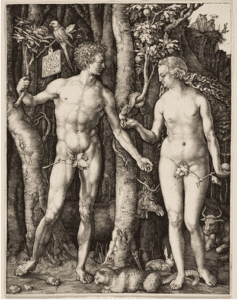

Up to the mid-1500s in Italy, the fig tree persisted in representing the Tree of Knowledge. Michelangelo, in 1535, painted a fig tree around which the serpent is coiled (Fig.2 ). However, the apple tree as the Tree of Knowledge was already becoming the more accepted version, especially in the works of the German artist Albrecht Dürer (Fig.3).

After Dürer’s 1504 engraving depicting the First Couple standing beside an apple tree, the apple dominated artworks recounting the Fall of Man and Woman.

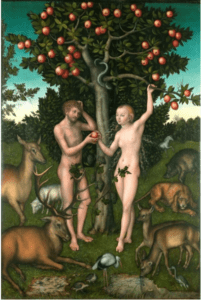

The apple tree became a template for later artists such as Lucas Cranach the Elder, whose luminous 1526 Adam and Eve painting displays a tree hung with apples that glow like rubies (Fig.4).

By the seventeenth century, when John Milton wrote Paradise Lost, the forbidden fruit was decidedly the apple.7

|

|

| Fig.3 Adam and Eve, 1504, Albrecht Durer, engraving, © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Apples have been cultivated for thousands of years, with all apples descending from the original apple cultivar from the Samarkand area in the steppes of central Asia, the Malus sieversii, before they were brought to Europe. The apple had already been elevated for millennia in culture and myth for its regenerative and salutary powers. Homer relates in the Iliad that an apple was given by Paris to the fairest goddess. He chose Aphrodite (Venus). An argument ensued among the goddesses, even as the Trojan Paris was being given Helen of Sparta as a prize by Aphrodite, which all led to the decade-long Trojan War (here mălum is both “apple” and a “bad” outcome). In the Odyssey, Odysseus (Ulysses) yearns to get back to Ithaka and his spouse Penelope, and to walk again in his garden, which was an apple orchard.7 The Golden Apples of the Hesperides were said to confer immortality. In the Norse Eddas, the goddess Iðunn provides apples to the gods that give them eternal youthfulness. The Arabian Nights feature a magic apple from Samarkand capable of curing all diseases.7

|

|

| Fig.4 Adam and Eve, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1526, ©Courtauld Institute, London |

In the present day, fruits and vegetables in their natural state are known to be healthy. A diet high in fruits and vegetables may decrease the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. Eating whole fruits and vegetables (and not skipping them in favor of megadoses of vitamins in pill form) provides not only vitamins and minerals, but a significant variety of antioxidants.3,4,5,7 Indeed, it may be the combination of antioxidants working in synergy, and not just a single antioxidant, that is the most likely mechanism for their salutary effects. 3,5,7

Apples have significant health benefits, depending on specific apple cultivars.2 Epidemiological studies have linked the consumption of apples with reduced risk of some cancers, cardiovascular disease, asthma, and diabetes. Apples are neuroprotective and lower cholesterol, as well as reducing blood pressure in some studies. The antioxidant properties of one fresh apple are equal to 1500 mg of Vitamin C (ascorbic acid),3,4 but in addition to Vitamin C, apples also contain retinoic acid (Vitamin A), thiamine (Vitamin B1), riboflavin (Vitamin B2), pyridoxine (Vitamin B6), and beneficial phytochemical antioxidants and anti-inflammatories: polyphenolic anthocyanidins and isoflavones, and the flavonols quercetin, catechin, phloridzin, and chlorogenic acid.2,3,5 These polyphenols and flavonoids also determine traits such as color, flavor, and bitterness (which explains why some apples are so-called “spitters” because of their bitterness—one immediately spits them out after biting into them—better to use those in ciders and brandies).2,3,4,5

Although apple peel accounts for a small percentage of whole fruit weight, its richness in phytochemicals contributes to additional health benefits.3,4,5 The antioxidant activity and bioactivity are higher in the peel than in the flesh. An apple with the peel contains 116 calories, no fat, and 5.4 grams of fiber.5 In addition, it provides about 240 milligrams of potassium, 10 milligrams of vitamin C, 120 international units of vitamin A, and about 5 micrograms of vitamin K.5 An apple without the peel is certainly a healthy food, but there is nutrient loss. An apple without the skin has about 100 calories and 3 grams of fiber, which is a significant difference compared to an apple with the skin, as eating plenty of fiber is helpful for gastrointestinal function.5 That same apple without the skin contains about 200 milligrams of potassium and 8.6 milligrams of vitamin C. There are about 80 international units of vitamin A and 1.3 micrograms of vitamin K in an apple without skin.5

Apples have other benefits. They contain malic acid (“malic” from malum), which helps reduce tooth decay by cleaning teeth and gums, is antimicrobial, and reduces halitosis. Can apples help fight cancer? The data is promising.6,8 Apple polyphenols inhibit cancer cell migration and induce apoptotic cancer cell death.3,6,8 A study that looked at treating isolates of colon cancer cells with extracts from apple skin, and separately, from apple flesh, demonstrated reduced cancer cell growth (43%, and 29% respectively).6 A similar study was done on liver cancer cells and the reductions were 57% and 40% respectively.6 Apple peels contain triterpenoids, which are not present in apple flesh, and could explain some of the increased benefit against cancer cell growth in the apple skin cohorts.5

There is thus much truth to the axiom that “eating an apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

But, don’t forget to eat the peel!

References

- An Apple a Day. Phrases.org https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/an-apple-a-day.html

- Almeida D, Giao M. Bioactive phytochemicals in apple cultivars. International Journal of Food Properties 2017; 10:2206-2214 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10942912.2016.123343

- Boyer, Liu R. Apple phytochemicals and their health benefits. Nutritional Journal 2004; 3: 5-19 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC442131/

- Boyles, S. An Apple a Day keeps the doctor away. WebMD June 21, 2000 https://www.webmd.com/food-recipes/news/20000621/benefits-of-eating-fruit#1

- Ipatenco S, Does the Apple Skin have the most nutrients? Livestrong 10/3/2017 https://www.livestrong.com/article/470237-does-the-apple-skin-have-the-most-nutrients/

- Li Y, Liu L, et al. Modified apple polysaccharide prevents against tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated colon cancer. Eur J Nutr 2012 51(1):107-17. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0194-3. Epub 2011 Apr 24.

- Rupp, Rebecca. The History of the Forbidden Fruit. July 2014 https://www.nationalgeographic.com/people-and-culture/food/the-plate/2014/07/22/history-of-apples/

- Tu S, Chen L, Ho Y. An apple a day to prevent cancer formation: reducing cancer risk with flavonoids J Food Drug Anal 2017; 25(1): 119 -124

VINCENT P. DE LUISE, MD, FACS is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Yale University School of Medicine, and adjunct clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medical College, where he serves on the Music and Medicine Initiative Advisory Board. He is a senior honor recipient of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and physician program co-chair of the Connecticut Society of Eye Physicians. A clarinetist and recitalist, Dr. de Luise is the Cultural Ambassador and program annotator of the Waterbury Symphony Orchestra and president of the Connecticut Summer Opera Foundation. He co-founded the annual classical music recital of the AAO, and writes frequently about music and the arts.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply