Sarah Kearns

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

|

|

| Tollund Man seems to be sleeping peacefully, perfectly preserved with his sheepskin cap upon his head—and noose around his neck. |

On a warm spring day in Denmark in 1950 two brothers, Viggo and Emil Hojgaard, ventured out into the marshlands to gather peat to make fuel. With hefty sharp spades, they cut out earthen bricks of decayed organic matter to be used as an energy source. During this laborious task, beads of sweat accumulating on their brows, their spades uncovered a source of shock and fear—a body with dark wrinkled skin, red facial stubble, in a sheepskin cap, peacefully sleeping despite the plaited noose around his neck. The brothers immediately went to the police, thinking they had found a victim of a recent gruesome murder. Much to their surprise, the hanged man was part of a cold case dating back 2,400 years.

The Tollund Man, as he is now known, is just one example of the hundreds of human corpses found in Northern European wetlands dating as far back as 8,000 BC.1 Many of these so-called “bog bodies” are perfectly preserved, their skin, internal organs, nails, hair, and clothes left in excellent condition.

The preservative paradoxically found in decaying peat moss is a molecule called sphagnan, an antibiotic that prevents rotting. By reacting with enzymes secreted by moldering bacteria, sphagnan prevents microbes from breaking down organic matter. 2 Not without consequence, the peat moss molecule also sequesters calcium from bones, leaving the skeleton rubbery, and dispels water from the tissue preventing circulation. As such, the bog bodies seem to be crudely cast out of bronzed leather and mud. Lacking drainage, the highly acidic anaerobic environment of the bogs also has aldehydes that saturate bodily tissues before decay can begin. Taken together, the chemical environment of the marshland creates the perfect setting for preserving soft tissues.

Such preservation provides valuable information about past cultures by preserving the bog bodies’ gastrointestinal systems and the contents of any last meals consumed.

As part of the examination of Tollund Man, forensic scientists surveyed the stomach and small intestine. Looking under the microscope at thinly sliced tissue samples called histograms, they found traces of barley, flaxseed, chamomile, and knotgrasses. While barley and flaxseed are cultivated in fields, knotgrass grows wild, suggesting a diet based on farming as well as foraging. This contrasts with the recent find that Otzi the Ice Man, who lived during the Copper Age and was found in the Italian Alps, consumed a high-fat diet full of protein from deer and ibex.3

Of course one meal does not reveal a lifetime or a culture’s entire diet. Uncovering villages from both Copper and Iron ages, archaeologists have found food stuck between the teeth of individuals in burial grounds or coating decorative clay containers, filling in missing information about the diets of these ancient cultures. Charred grains of barley, poppy seeds, nuts, and berries indicate foraging as a means of sustenance, which supplemented the growing trend of harvesting and of domesticating animals such as pigs and cattle.

The dank acidic environment of the peat is the perfect place to preserve half-digested food and also the ideal hiding place to dispose of a body. Postmortem histology can reveal clues about past cultures as well as probing into causes of death. The Tollund Man, found with a rope around his neck, had evidently been hanged before being tossed in the decaying bog. In many cases, the found corpses are of people who once committed “deeds of shame”—adulterers, cowards during war-time, sodomites, and those who committed suicide.4 Despite being buried unceremoniously, these bodies in the bogs were ironically better preserved than those given traditional graves.

Autopsies are also performed to probe into the causes of death, starting with human dissections dating to the Renaissance, and the first forensic autopsy being done in the early 1300s in Bologna after the suspicious death of a prominent political leader.5 While autopsies of that era were performed sparingly, they aimed, as they do today, to determine whether a victim died from natural or criminal causes such as a heart attack or poisoning. Not until the mid-1800s were autopsy standards set and each organ of the body documented. Even now, forensic practices and methods are being modified to ensure fair judgements in court based on scientific evidence.6

During an autopsy, the victims’ stomachs and intestines are removed and examined to help determine the time of death. As the gastrointestinal tract stops functioning after death, it creates a time capsule of the victim’s last moments, since a meal is typically digested within six hours. The last meal can mark death within an hour or two and has been used to support alibis and convict killers.

|

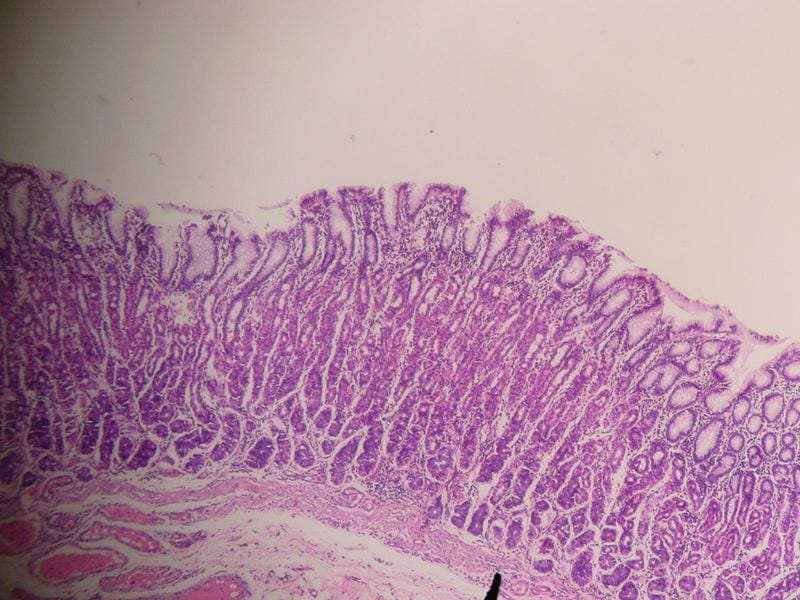

| Small pores in the lining of the stomach secrete digestive enzymes to break down consumed food. Using a stain called eosin, cells are turned a bright pink-purple color to be viewed more easily under the microscope. |

When in 1982 a young woman in eastern Colorado just outside of Denver was found dead, her boyfriend became the primary suspect. He testified that their last meal together had been at McDonald’s the day before. The forensic pathologist first followed standard practice, making Y-shaped incisions from each shoulder joint to joint mid-chest, examining her organs by freeing out the intestines. Stumped, he then turned to an unlikely pair for help with the case: a botanist and an animal ecologist. These two, Jane Bock and David Norris, inadvertently becoming forensic investigators, obtained the histogram slide set of the victim’s stomach contents and were able to identify small pieces of half-digested green peppers, red cabbage, and kidney beans. This indicated that after her hamburger meal with her boyfriend the victim must have eaten somewhere else—perhaps with someone else.

Foods containing a cell wall, such as fruit and vegetables, remain more intact in the acidic environment of the stomach than other kinds of food.7 The skeletal muscle of meat pretty much all looks the same after being exposed to stomach acids, turning quickly into a porous mush to be absorbed, but plants’ fibrous cell wall make them harder to be digested and therefore easier to identify later. Thus finding the cellulose of salad components in the Colorado case led the police to the salad bar of a local Wendy’s—the only fast food place that served leafy greens. There, the waitress confirmed that she had seen the woman leave with another man on the afternoon of her death, freeing the boyfriend from being the primary suspect. Years later, a serial killer named Henry Lee Lucas confessed to her murder.8 Yet another famous case was also solved forensically, by identifying half-digested hash browns caught in victim Gerry Boggs’ entrails—the last husband and casualty of serial marrier and murderer Jill Coit.

But the subjects of these forensic case studies are not the only people to die with a full stomach. Having cut short the lives and digestive processes of their victims, inmates on death row in US prisons, regardless of their crime, are given the humanity and privilege of a last meal of their choosing and may request whatever they want, ranging from a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken to shots of Jack Daniels (provided it fits into the prison budget).9 Served minutes before death, the choice of this “special meal” spans continents and cultures and offers a poignant insight into the value of fulfillment through consumption. Culinary choices often are impacted by memories, culture, and gender, and offer a final moral or philosophical statement that most of us will not have the opportunity to make.10

References

- Fischer, C. Tollundman. Gaven til guderne. 2007.

- Stalheim, T., S. Ballance, B. E. Christensen, and P. E. Granum. “Sphagnan – a Pectin-like Polymer Isolated From Sphagnum moss Can Inhibit the Growth of Some Typical Food Spoilage and Food Poisoning Bacteria by Lowering the pH.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 106, no. 3 (2009): 967-76. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04057.x.

- Frank, Maixner, et al. “The Iceman’s Last Meal Consisted of Fat, Wild Meat, and Cereals.” Cell Press 28 (July 23, 2018): 2348-355. July 12, 2018. Accessed September 2, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.067.

- Sanders, K. Bog Bodies and the Archaeological Imagination. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- “The History of Autopsy.” Events Leading Up To World War I Timeline | Preceden. Accessed September 02, 2018. https://www.preceden.com/timelines/69133-the-history-of-autopsy-.

- Lander, Eric S. “Fix the Flaws in Forensic Science.” The New York Times. April 21, 2015. Accessed September 02, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/21/opinion/fix-the-flaws-in-forensic-science.html.

- Bock, Jane H., and David O. Norris. Forensic Plant Science. Amsterdam: Elsevier/AP (2016).

- Migration. “Serial Killers Worked Denver Streets from ’75 to ’95, Police Say.” The Denver Post. April 28, 2016. Accessed September 02, 2018. https://www.denverpost.com/2012/09/01/serial-killers-worked-denver-streets-from-75-to-95-police-say/.

- Dickinson, Ian. “What 30 Of History’s Most Monstrous Criminals Had For Their Last Meal.” All That’s Interesting. February 06, 2018. Accessed September 02, 2018. https://allthatsinteresting.com/last-meals-executed-criminals#9.

- Jones. “Dining on Death Row: Last Meals and the Crutch of Ritual.” The Journal of American Folklore 127, no. 503 (Winter 2014): 3-26. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.127.503.0003.

SARAH KEARNS is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Chemical Biology program at the University of Michigan. She is interested in intercellular trafficking and how cargo is transported along molecular roads called microtubules. Using microscopy and structural biology, she looks at chemical modifications to microtubules that act as “road signs” for transport. Sarah is also a senior editor of a graduate student run blog, Michigan Science Writers. She contributes to her own blog, Annotated Science, and advocates for open access and scientific literacy.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply