Catherine Lanser

Madison, Wisconsin, USA

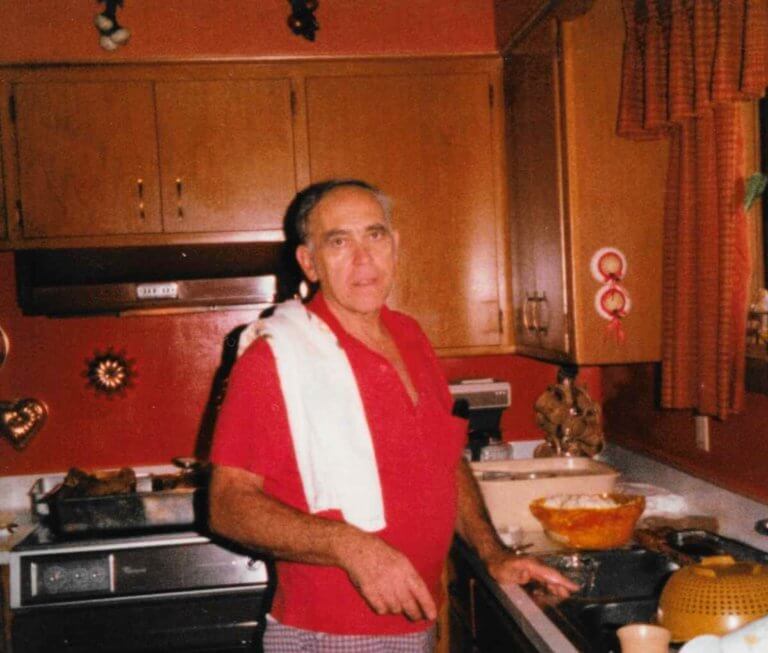

My brother Rick’s house was warm with the scent of food. He had made huge pans of lasagna to comfort my family a few weeks after my dad’s stroke. My mom, eight siblings, in-laws, nieces, and nephews sat in groups around the house wherever we could fit. Rick stood hunched against the kitchen counter eating from his plate.

Though we had spent the past weeks discussing our dad’s health, the conversation that night focused on the food, as it always did when Rick cooked. We once spent an entire meal discussing capers because no one in my family had ever eaten them before. He had also introduced us to buffalo mozzarella and wasabi peas. This evening he served us roasted garlic and taught us how to spread it on crusty bread.

The lasagna was perfectly layered with sweet and spicy rich Italian sausage, gooey cheese, and just the right amount of sauce. The salad was beautiful; an enormous bowl of greens, homemade gingerbread croutons, goat cheese, and pomegranate seeds.

Later, on the twenty-minute car ride back to my parents’ house, we continued to dissect the meal. Not everyone cared for the salad. I was the only one who liked goat cheese. My sister-in-law had not tried the roasted garlic. But everyone loved the lasagna.

I knew my dad would have loved it, too. It was not the recipe he would have made, a little thin and watery, with ground beef, but he still would have inhaled every morsel. It was the kind of night I wished he could enjoy again. It almost felt as if we were betraying him by indulging our senses when he could not.

Now instead of food, he received nutrition that looked like wood glue. Precious areas of his brain had died the morning my mom found him lying in the hallway, trying to get to the kitchen for some aspirin. A blood vessel had burst, damaging his brain stem and cerebellum. Now he sat slumped in a wheelchair, his arms splayed out or on his lap since his brain was no longer capable of coordinating the movements or providing the balance needed to walk. He also had tremors and one of his arms moved in circles when he tried to reach for something.

But losing the ability to swallow and to eat anything by mouth may have been the cruelest loss. He failed to recognize that the tube flopping out from his abdomen was doing the work his mouth once did. We scrambled to wipe off the constant stream of saliva that ran down his face. Even without food he would choke on his spit and cough profusely. When he opened his mouth to talk, his speech was garbled and incoherent, making communication nearly impossible.

As the months wore on, he would improve in other areas, gaining some balance and the ability to move about in his wheelchair and walk a little with a walker, but his essence never returned, and he never was able to eat.

At first, he did not miss it. But one afternoon three months after the stroke, my sister Pattie and I saw his appetite reawaken. The rehabilitation hospital offered free soup, salad, and rolls to patients’ families. Since the facility was in the middle of nowhere we were excited at first, but soon found the food repulsive. As we shoveled lifeless salad into our mouths, my sister and I talked to each other, almost forgetting our dad was there. A few minutes into our meal, my dad’s hand landed heavy on Pattie’s tray. His fingers made tiny straining movements to pull the plate with a roll on it closer to him.

We looked at each other, realizing what was happening. I distracted him as Pattie pulled the tray away. We knew even a small bit of food, especially a dry roll like the one he was reaching for, would make him cough uncontrollably. He oriented himself toward the tray and began the movements again. I distracted him again, while Pattie took the trays and threw the food away.

“I guess we better not do this in front of him anymore,” she said.

But there was no way to put his hunger to sleep. Next, he moved to a nursing home where the dining room looked like a restaurant. It drew my dad like a magnet, especially since he did not have anything to do while the other residents ate. By then he was quite mobile, using his feet to pull himself in his wheelchair. The aroma of the dinners drew him and slurping and scraping sounds alerted him to others eating. Even the place settings were enough to draw him in, as if there might be something coming or even left behind from the previous meal. His hands probed the table, reaching for anything he could find to fill his insatiable desire.

He went into other residents’ rooms, unsure of where he was going to look for food. Though he was talking more, thanks to speech therapy, many conversations were still jumbled or nonsensical. The front doors were a fascination for him; he wanted to escape to go home or to the McDonald’s that taunted him next door.

He saw it the first day he was transferred to the nursing home. The staff had not received feeding orders until the afternoon, which delayed his tube feeding until 5:30 that evening. Since he had not received any nutrition since morning, he was hungry. At one point while he was waiting to be fed, he pedaled off in his wheelchair, telling my mom he was going to get them some chicken sandwiches, no doubt from McDonald’s. The golden arches could be seen clearly through the windows, and from that day forward reaching them became his goal. He had never been a big fast food eater, but now the scent of fries and burgers wafting through the air called to him. It seemed to pick on the one sense that was still alive and active in his brain.

More than a year after the stroke, we were finally able to bring my dad home. He received daily nutrition through his G-tube but his desire to eat never waned. It occurred to me that he did not know why he could not eat. I doubted he knew that the nutrients pumped in through the tube in his stomach were food because they were not at all appetizing. Or that the coughing caused by his saliva would be ten times be worse with food. Without taste, texture, and the ability to swallow, it must have felt as if we were starving him.

One day, shortly after he came home, he snatched a Styrofoam apple from a decorative bowl on the table and took a bite. It was the same way he used to eat apples with abandon, even the ones I would consider too bruised, soft, or sour, taking enormous bites that cut the apple in half and exposed the seeds at the core.

I thought back to an earlier time, snacking on leftovers together the day after Christmas. My dad was eating caramel corn when he started to move his mouth around, fishing inside with his tongue. He waited for a lull in the conversation and then pulled something out of his mouth.

“I just lost a tooth,” he said.

“What?” Our heads snapped toward him.

“What happened?” my mom asked.

“I guess it got caught on a peanut or something,” he said. “And it just came right out.”

“It just came right out?” she asked.

“Yep,” he said, smiling exaggeratedly, showing us his new gap-toothed smile. He closed his mouth and explored the area around the missing tooth. “I guess I’ll have to go to the dentist.”

He put the tooth on the windowsill in the kitchen until he could see the dentist a few days later.

Now, reaching into his mouth to retrieve the fake apple, trying to avoid being bitten, I hoped that apple tasted as sweet as that memory did to me.

CATHERINE LANSER is a writer from Madison, Wisconsin. She writes essays and narrative nonfiction about her life in the Midwest and growing up as the baby of a family of nine children. This piece is an excerpt from her first full-length memoir about how she found her place in her family, told through the lens of her brain tumor and her father’s stroke. She blogs at www.catherinelanser.com/blog.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019