George W. Christopher

Ada, Michigan, United States

A quick glance at the afternoon clinic schedule revealed that the next patient was scheduled to “Rule out HIV infection.” I knocked on the door, entered the exam room, and began introductions. The patient was young, anxious, and struggling to maintain a stoic façade.

“I have HIV infection.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, I’m positive.”

It was the early 1990s, before the introduction of medications that could suppress the viral load. The only available anti-retroviral treatments could improve quality of life and life expectancy, but in the end simply delayed the inevitable. HIV infection was the leading cause of death in the 25 to 44-year-old age group in the United States,1 and was even more devastating in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world.

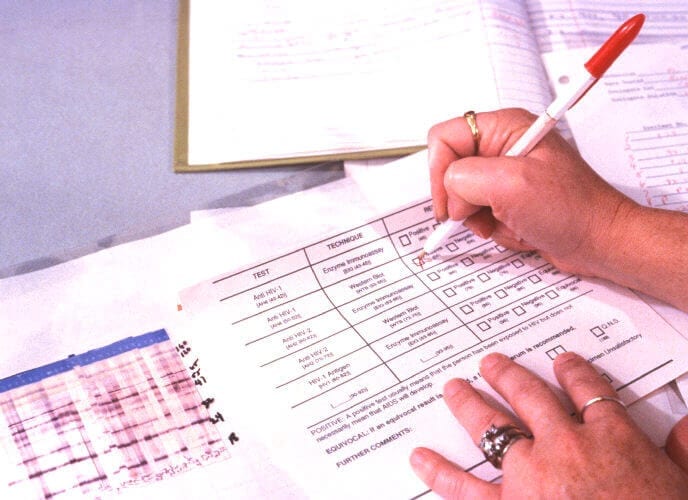

I reviewed the patient’s medical history and the events that led to the referral. A screening test for blood donors had been positive, followed by two confirmatory tests taken months apart that gave identical—but indeterminate—results. By history the patient was at low risk for HIV infection; she also denied unexplained fever, weight loss, rashes, cough, or shortness of breath. A cursory physical exam did not reveal anything concerning.

I began to explain the difference between true- and false-positive test results, sensitivity versus specificity, and the trade-offs made in using high sensitivity but low specificity tests for screening. I engaged the help of a new tool called the Internet to help the patient better understand the interpretation of HIV test results.2, 3

“Your Western blot tests only show one band, your p24 bands are negative, and there was no progression between the two tests. False positive results can occur in people sensitized to certain human proteins during pregnancy, blood transfusions, or inflammation. The antibodies cross-react on the test. You have a false-positive screening test result. You do not have HIV infection.”

“Are you sure?” she asked.

“Yes, I’m positive.”

Believing that every opportunity should be taken to discuss prevention, I launched into a well-worn monologue on methods of HIV transmission and avoidance of risk. I paused, surprised. The patient was in tears.

“Should this discussion wait for another time?” I asked.

“Yes,” she replied. “I’m positive.”

Note from the author

Although this fictionalized account is based on a medical consultation that took place over twenty-five years ago, the issues raised are still relevant today.4-7 The contrast between certainty and ambiguity, the challenges of practicing the art of medicine in the haze of diagnostic uncertainty, the risks of an iatrogenic complication (anxiety) due to the misinterpretation of high sensitivity/low specificity test results in low-risk individuals, and the importance of communication in a therapeutic alliance are all intrinsic to medical practice. In this story, the patient may have needed more time to process emotion after an enormous burden had been lifted, and the clinician may have needed more time to grow in perception and sensitivity.

Although HIV testing was imperfect in 1993, it was an improvement over the capability of the first four years of the AIDS epidemic, when no etiologic agent-directed testing was available (an inevitable and recurring challenge in the context of new emerging diseases). Clinicians were limited to clinical case definitions supplemented by lymphocyte subset counts as surrogate laboratory markers. The movements from early antibody-based tests that gave up to 10-20% indeterminate results,3 to the current “fourth generation” antigen/antibody combination immunoassays and nucleic acid tests;8,9 and from high-complexity tests done only at reference laboratories to simplified point-of-care and over-the-counter home tests, are all steps forward.10

The patient in this story responded to a medical intervention, which in this case was an explanation of the test results. Yet one of the few certainties in this tale is that there may be times when empathy calls for the deferral of specific medical interventions, even if they seem innocuous to the clinician, such as a discussion on disease transmission and prevention.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Mortality attributable to HIV infection among persons aged 25-44 years—United States, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996:45:121-5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interpretation of Western blot assay for serodiagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38(S-7);1-7

- Celum CL, Coombs RW, Lafferty W, et al. Indeterminate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Western blots: Seroconversion risk, specificity of supplemental tests, and an algorithm for evaluation. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:656-64.

- Kiely P, Hoad VC, Wood EM. False positive viral marker results in blood donors and their unintended consequences. Vox Sang. 2018 jul 4. doi: 10.1111/vox.12675. Epub ahead of print. Accessed July 28, 2018.

- Vernooij van-Langen EM, van der Pal SM, Reijntiens AJ, Loeber JG, Dompling E, Dankert-Roelse JE. Parental knowledge reduces long term anxiety induced by false-positive test results after newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Mol Gen Metab Rep. 2014 Aug 1;1:334-344.

- Hafslund B, Espenhaug B, Nordtvet MW. Effects of false-positive mammogram results in a breast screening program on anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life. Cancer Nurs. 2012 Sep-Oct;35(5):E26-34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182341ddb.

- Tosteson AN, Fryback DG, Hammond CS, Hanna LG, Grove MR, Brown M, Wang Q, et al. Consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. JAMA Int Med. 2014 Jun;174(6):954-61. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.981.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories. Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: Updated Recommendations. Published June 27, 2014. Available at http:/stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/23447. Accessed July 23, 2018

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories. 2018 Quick reference guide: Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. Available at http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/50872. Accessed July 23, 2018.

- Figueroa C, Johnson C, Ford N, Sanders A, et al. Reliability of HIV rapid diagnostic tests for self-testing compared with testing by health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2018;Jun;5(6):e277-90.

GEORGE W. CHRISTOPHER, MD, is a retired infectious diseases physician. He lives with his lovely wife, Linda, near the older of their two sons, his wife, and two grandchildren in western Michigan.

Leave a Reply