Michael Shulman

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

|

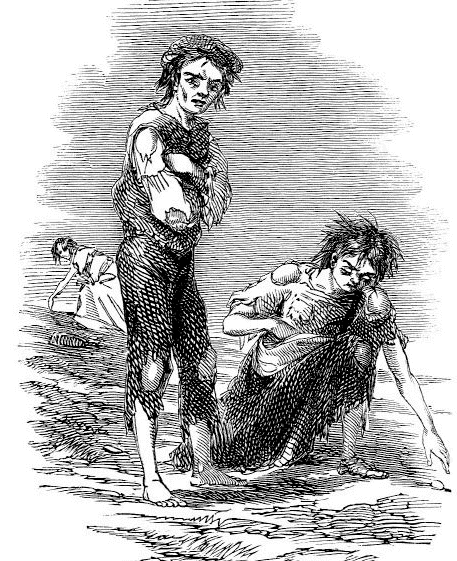

| “Boy and Girl at Cahera” (1847) Image of the Great Famine for middle-class readers of London Illustrated News. |

The mystery of Food

Increased till I abjured it

And dine without Like God

— Emily Dickinson

Susan Sontag’s 1978 essay Illness as Metaphor,1 published in serial form in The New York Review of Books, was a cultural event that continues to stimulate reflection and analysis forty years later. Based on an examination of texts beginning with the Greeks and ending with Norman Mailer, Sontag pointed out the many ways in which artists and intellectuals have distorted the physical reality of illness by interpreting it in aesthetic or psychological terms. But while the essay is admirable for its scholarship and good intentions, as a polemic it is unconvincing. For example, an attempt to show that the metaphors attached to tuberculosis in the nineteenth century (passion, creative ecstasy) are opposed to those attached to cancer in the present day (repression, social isolation) is contradicted by some of Sontag’s own citations. Indeed, the claim that death due to cancer, unlike TB, never invites flattering metaphors is contradicted by her own eulogy: “She was always in the front line for any daring new treatment,” wrote Christopher Hitchens after her death from leukemia.2 Most damaging of all is her failure to make any distinction between “metaphorical thinking” and the punitive or dismissive attitudes toward illness that merely rely on metaphor for rhetorical effect.

Where Sontag does succeed, however, is in creating a sociology of illness. In the manner of post-modern analysis, her focus on texts exposes the highbrow view of illness as simply the medium in which some persons choose to express themselves. It is an illuminating approach, one that reveals secret meaning in the literary treatment of another physical affliction—starvation. Like illness, starvation is a biological event. Unlike illness, it is always a great agony. But a survey of centuries of literature and commentary reveals that starvation, like illness, invites metaphors that transform it from a physical torment into the bodily expression of a transcendental idea.

As befits an era of religious fundamentalism, starvation in the Middle Ages was a metaphor for febrile piety. The narrative of Piers Plowman, a devotional poem written in the late 1300’s, paid tribute to Mary Magdalene, who lived on only “roots and dew.” Asceticism is a competitive sport, however, and feasting on “roots and dew,” viewed abstemiously, can be construed a form of gluttony. This was the epoch of Alpaïs of Cudot, the Catholic saint whose biography written in 1180 claimed she received sustenance from the Holy Communion alone. Augustine in his Confessions also saw virtue in habitual starvation. “I carry on a daily war by fasting,” he wrote, “constantly bringing my body into subjection.”

Starvation, at least regarded from on high, has never quite lost its cachet as a form of suffering that is also a commendable and status-conferring sacrifice. Passing over many centuries, Christina Rossetti, caught up in the medievalism of the Oxford movement of the 1830’s, might have been a tonsured monk when in The Face of the Deep she extolled the duty of fasting, “Self must be stinted, selfishness starved.”

Increasingly, however, nineteenth century intellectuals accommodated to the strictures of the middle class, viewing starvation as a fate that lamentably but befittingly strikes life’s vulnerable creatures—women and the poor. Boyce points to the engraving “Boy and Girl at Cahera,” which appeared in Illustrated London News in 1847 during the Great Famine in Ireland.3 The boy is shabby and ill-countenanced. His female companion claws at the earth, scavenging like an animal. It is a graphic metaphor for the genteel view of starvation as a horror, but a horror mitigated a little because the starving poor lead a life suited to their natural inclination.

Many novels and poems of the Victorian age regarded starvation as a metaphor not only for the bestial nature of the poor but for the biologically subordinate role of women. Charlotte Bronte’s protagonists Caroline Helstone and Shirley (in the novel Shirley) starve because they are tied to boorish men and have been warned against assertively opening their mouths. They do not rebel, however. Their posture is one of regretful submission. They are a trifle more human than the women in Dickens who starve because the Victorian view of maternalism means appeasing every appetite except one’s own. Little Nell, the angelic protagonist of The Old Curiosity Shop, has a “loathing of food.” She dies “patient, noble,” surrounded by tear-soaked witnesses and enough treacly sentiment to feed a Victorian workhouse. Queen Victoria herself read Dickens’s account of the heavenward ascent of the fatally undernourished Nell. It was reported that she approved.

Artists in the last century, discovering themselves not displeasingly alienated from the masses, were apt to see starvation as desirable not because it upheld Victorian scruples but because it defied them. In A Hunger Artist, Kafka created a protagonist whose carefully cultivated art form is to starve in public. He dies in a circus sideshow, an overlooked attraction in a tiny cage, like a Rive Gauche poet expiring in a garret filled with unpublished masterpieces. James Joyce, in Ulysses, had his alter ego Stephen Dedalus spurn solid food, an act of rebellion against the vulgar appetites of Dublin, appetites appeased only when the artistic temperament is sottishly and decisively squelched.

|

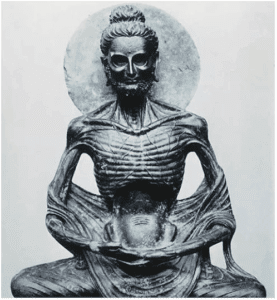

| Emaciated Buddha |

When George Orwell, recoiling from his own brutalities as a colonial policeman in Burma, chose briefly to starve in the slums of Paris, he relished his empty stomach as an offering of imperialist atonement. Later he wrote “The Politics of Starvation,” reimagining hunger as a symbol for the sins of imperialism. Starvation has remained inseparable from politics ever since. But if starvation has become a universal metaphor for the plight of the dispossessed, the spirit of our age has turned it into a metaphor colored ever more luridly by exhalations of rage.

Richard Wright’s autobiographical novel Black Boy captured this spirit precisely, treating the grumbling of an empty belly as if it were a street disturbance protesting racial abuse. “It was hunger,” he writes, “hunger that kept me on edge, that made my temper flare, hunger that made hate leap out of my heart.” Vincent Buckley’s poem “Hunger-Strike” commemorated the starvation death of Bobby Sands in HM Prison Maze, portraying him as a militaristic saint “with no weapon other than the sticks of his forearms.” In Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer prize-winning novel Beloved, the escaped slave Sethe refuses to eat, reenacting the defiance of kidnapped Africans condemned to the unspeakably cruel conditions of slave ships. Starving in all these cases affirms the essential paradox of martyrdom. It is a personal triumph, but one that can only be attained by descending the path to personal extinction.

The metaphors of starvation, as Sontag observes of the metaphors of illness, are troubling because they withdraw sympathy and offer “meaning” in its place, with “meaning” serving as an excuse for neglect. But can this truly be blamed on the metaphors themselves? Sontag never defends her assertion that “the healthiest way of being ill is one most purified . . . of metaphoric thinking.”4 She would find it hard to do so. It was William Osler, never one to cheapen illness with sentiment, who wrote “nothing will sustain you more potently [in medicine] than the power to recognize . . . the poetry of the ordinary man.”4 Metaphors provide us with the language that instills hope and shores up courage. Clinicians who sincerely wish to enlighten patients know that well-chosen metaphors are vastly more useful than medical jargon, which merely provides the illusion of shared knowledge. And when suffering is terminal, and it is no longer possible to speak of cure, metaphor is the natural language of consolation and remembrance.

But if metaphor is not the toxic element Sontag claims, how to explain the stigmatizing of illness in her literary sources? Undergirding the attitudes Sontag documents so well is the ancient belief in an immaterial self trapped in the body like a bird in a cage. This mind-body dualism need not be malignant, but great damage is done once the spirit is imagined to be a mere spectator of corporeal starvation. Perversely in those instances, the ebbing of one’s own vital energy may be welcomed as a sign of devotion, or a proof of femininity, or a token of moral authority over society’s powerbrokers. When Sontag complains of metaphorical thinking, it is usually this rather more destructive habit of mind she is deploring. And she is quite right to call attention to the weakening of the impulse to cure or palliate that occurs if illness is regarded as a half-willed manifestation of our true selves.

After a surfeit of the philosophy of starvation as spiritual cleansing, the plainspokenness of Camus’s novel The Plague seems positively Solomonic: “. . . there are pestilences and there are victims, and as far as possible, one must refuse to be on the side of the pestilence.” By this logic— the logic that defends health over illness—the romanticized view of fasting as a sacred weapon, or a feminine virtue, or a mantle of holiness must place one unconscionably “on the side” of starvation, not because the thinking is metaphorical but because the thinking is inimical to life. Starving, looked at coldly, is not different from rotting. Philosophers and artists who perceive nobility in going hungry are giving starvation—degrading, painful, and unnecessary—a halo it does not deserve.

And yet neither mind-body dualism nor injudicious metaphors can fully explain the human willingness to spurn instinct and to elect instead to starve. Kafka’s Hunger Artist was modeled after real-life performers who circulated in Europe in the 1930s, showcasing their fasts as public entertainment. “Paris,” claimed the Spanish novelist Carlos Ruiz Zafón, “is the only city where starving to death is still considered an art.”5 Alas, self-mortification is not so provincial. There is nowhere in the world that a gaunt visage does not give off an aura of holiness. What we require, pace Sontag, is not a language stripped of metaphor—that would only impoverish us—but an ethos that does not romanticize suffering. For all the saintliness surrounding it, starvation is a curse, a remediable one, a diabolical visitor that every life-affirming impulse demands we expel from its place of privilege among the human miseries.

References

- Sontag S. Illness as metaphor. New York: Farrar. Strauss and Giroux. 1978. 2. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/obit/2004/12/susan_sontag.html [Hitchens C. Susan Sontag: Remembering an intellectual heroine.

- Boyce C. Victorian Literature and Culture. Representing the “Hungry Forties” in image and verse: The politics of hunger in early Victorian illustrated periodicals. 2012; 40:421–449.

- Bryan CS. Caring carefully: Sir William Osler on the issue of competence vs compassion in medicine. Baylor U Medical Center Proc. 1999;12(4): 277-284.

- Ruiz Zafón C. The shadow of the wind (L. Graves, Trans.). London, UK: Orion. 2004.

MICHAEL D. SHULMAN holds a PhD in clinical psychology from Fordham University and a medical degree from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is retired from the private practice of nephrology.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply