Wilson F. Engel, III

Gilbert, Arizona, USA

|

| Judy Chicago, Detail of ceramic representations of body parts on dinner plates from, The Dinner Party, Installation 1970s. Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York |

The Dinner Party, Judy Chicago’s now-famous mixed-media installation in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York, was an intentionally shocking feminist statement in the late 1970s.

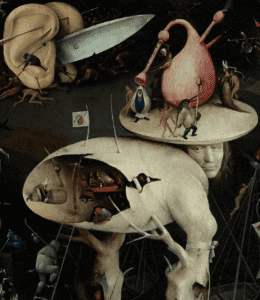

Chicago’s work was anticipated in important respects in an unorthodox altarpiece The Garden of Earthly Delights, the triptych oil painting on oak panel by the Northern Renaissance master Hieronymus Bosch, fl. 1500 AD, now residing in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

|

|

| Detail from Right Panel of Hieronymous Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Oil on Wood Tryptich, 1500 AD. Museo del Prado, Madrid |

Both Chicago and Bosch pictured universal feasts, underscored with boldly carnal and even savage references in anatomically correct bodily parts and mythical, metaphorical and religious visual references. Judy Chicago (and her helpers) celebrated 39 unsung, yet worthy, mythical and historical heroines, whose place settings at a fictive dinner table designed as an equilateral triangle (also as a female delta or pudenda) are complemented by homage to 999 named women (999 inverting or baffling 666—the Hebrew number for man), who made their marks on history. Less specific, but no less carnally expressed by Bosch, are numerous naked male and female figures as well as cracked and impaled organ representations in Eden (left panel), the world (center panel) and hell (right panel). The nearly clinical rendering of organs in both masterworks negates any vantage for sensuous innuendo, though biting satire is evident.

|

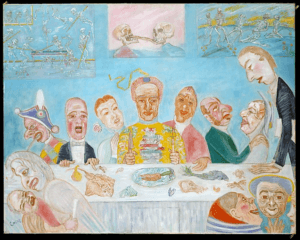

| James Ensor, Comical Repast Banquet of the Starved, 1860. Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The plated ceramic female organs in Chicago’s now-perpetual meal are complemented by chalices and ceremonial napkins lined with gold. Bosch’s images of gigantic fruits, often interposed over human genitalia and arrayed for animals as well as humans to dine upon, inevitably carry their historical, symbolic meanings, but, like Chicago’s 3-D art works, they have general, not specific reference. That Chicago knew Bosch’s work from ubiquitous color reproductions is all but certain, but the Renaissance master’s influence is not direct, but allusive. For example, Bosch’s tryptich is by definition, a three-part construct that closes on itself, as Chicago’s equilateral table does. Of course, symbolic meals abound in Western art.

The Dutch painting tradition is full of feasts celebrating (or castigating) gluttony. The Last Supper is a favorite subject for “the good feast,” while Salome’s Feast is for “the evil meal.”

Flemish-Belgian painter and printmaker James Sidney Edouard, Baron Ensor’s Banquet of the Starved (1860), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, satirically reverses expectations for both the Last Supper and Salome’s Feast by reference to the political theme of starvation while implying a triangular tableau whereby the viewer participates in his composition.

Like Ensor’s well-known work, Christopher Rowan’s satirical drawing, Bats in the Belfry (2011), mocks the refined banquet traditions, but with a triangular table like Chicago’s and a figure of death at its head, the festooned curtains seeming like death’s spread wings. While threatening, Rowan’s work invites no explicit participation by the viewer in the feast. Bosch’s tryptich, to the contrary, implied participation through including the entire framework of salvation as its compass. Chicago’s installation also invites participation—but by women only. As for the satirical intent in feasts from Ensor forward, some Western artists seem to discount the celebratory nature of group meals while accentuating the savage or unholy perversions of their original purpose and forms.

WILSON F. ENGEL, III, PhD, is a Shakespeare scholar and long-time student of the influences of the Classics on Christian life and thought in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. He was founder and editor of the scholarly newsletter Renaissance and Renascences in Western Literature.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply