Dhastagir Sultan Sheriff

Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

Changing patterns of weather and rainfall, past policies regarding water release and storage, and a frequently resultant dry basin have forced the central and state governments of India to engage in conserving water, often looking at ways to adapt ancient and traditional techniques that are simple, reliable, and environmentally friendly.1

In Indian culture water is linked to every social aspect of life. Divine water is consumed in the temple after puja worship rituals; idols of worship are sprinkled with water (abhishekam); and a plantain leaf kept for a meal is cleaned with water and a prayer. Many other rituals also highlight the significance of water in Indian culture. The Holy River Ganges is mythologically linked to Lord Shiva as the fountain that flows through the Himalayan terrain, reaching first Haridwar and then Benares. All over India people throng for a dip in the holy river to wash away their sins, for the Holy River Ganges is the Hindu symbol for purification of the soul and rejuvenation of the mind. (Fig.2.)1

Other rivers, such as the Brahamaputra, Indus, Godavari, Krishna, Narmada, Cauveri, and Mahanadi, are also symbolic places in Indian culture with thriving agriculture and plantations on their shores. The river Cauvery is linked closely to the culture, tradition, and history of the state of Tamilnadu. The Aadi Perukku festival (Adi means a Tamil month, Perukku means swelling) is celebrated in mid-July when the river is in full flow; and the Mettur Dam is built across it, storing water to release for the cultivation of wet lands.2

During the Aadi Perukku the water level reaches the maximum height of the dam (nearly 120 feet). The water is then released to benefit farmers with cultivation and irrigation. During the festival people throng the dam and its surroundings to offer pujas (prayers) to Cauvery, the mother. The weapons adorning the temple gods are cleaned on the eighteenth day of the month Aadi to commemorate the eighteen long days of battle between Pandavas and Gauravs, mythological characters of Mahabharatha. During the second century AD the Kallanai dam near Tiruchirappalli was built with stones by Karikalan, a king of the Chola dynasty. The river Cauvery and all rivers are worshipped as mother, for the river water sustains life for agriculture, the main source of revenue for farmers and the government.4

taking a holy dip in the river

the dam is 214 feet high, 171 feet wide,

and 5660 feet long.3

system in Tamilnadu

A recent dispute over sharing Cauvery water by the states of Karnataka (the origin of the river), Tamilnadu, and Kerala underscores how closely the life of the people revolves around this river.5 Every year the river water is further diminished because of climate change, so water conservation has become the most important goal in agriculture. The dams that previously helped in conservation no longer receive enough water, and even during the month Aadi the Mettur Dam does not fill to its full capacity.

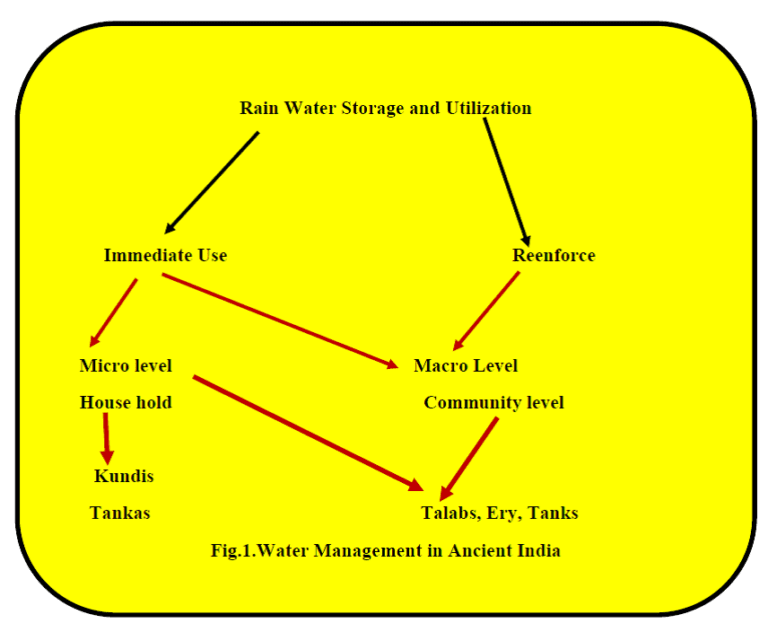

One of the oldest water management systems in Tamilnadu is known as ery or tank management. There are two types: system erys helping to store both river water and rain, and non-system erys storing only rain water. This system helps to control floods, store rainwater for paddy cultivation, recharge ground water, and curtail soil erosion.

Urbanization has led to the construction of buildings right into ancient water reservoirs such as lakes and ponds, such as in the city of Chennai and its surroundings. Such encroachments impede the flow of water during heavy rainy seasons, causing heavy floods, loss of property, devastation, and destruction, such as was seen in Chennai city in 2015.6,7

Like Tamilnadu, every state in India has ancient systems of water conservation and reservoirs.1 Jhalaras are rectangular step wells that absorb water seepage from the subterranean region of an upstream reservoir or lake, and may be seen in Rajasthan.

Jhalaras formed a supply channel to distribute water for religious rites, royal ceremonies, and community use. Bawaris are another type of step well, storing water that might percolate into the ground and raise water table levels. To minimize water loss through evaporation, a series of layered steps were built around the reservoirs to narrow and deepen the wells.

Talabs are another form of reservoirs that store water for household consumption and drinking purposes in Udaipur. Depending on the area, such reservoirs are called talai, bandhi, and sagar or samand. Traditional floodwater harvesting systems indigenous to South Bihar are known as Ahar-Pynes.

Johads are one of the oldest systems of ground water conservation and recharge. These small earthen check dams, called madakas in Karnataka and pemghara in Odisha, store rainwater. Wooden cylinders measuring four feet in diameter and depth and made of natural palm stems are used to store water in Waynad, in Kerala State.

A kund is a saucer-shaped catchment area that gently slopes toward a central circular underground well. Its main purpose is to harvest rainwater for drinking. Kunds dot the sandier tracts of western Rajasthan and Gujarat and are covered with lime and ash as disinfectant.

Baolis, with their beautiful arches, carved motifs, and additional rooms, are also step wells for storage and distribution. Nadis are village ponds for storing water from erratic rainfall. The Mewar Krishak Vikas Samiti (MKVS) is an organization that prevents sand sediments by adding spillways and silt traps.1 People in and around Tuticorin and Kanyakumari collect rainwater in big brass vessels and store them in their houses, later boiling it for drinking. Keralites also store and boil rainwater and then add cumin seeds (siragam) before drinking.1

The ancient wisdom of water conservation is a collective vision of our ancestors, who wanted future generations to benefit from it. We need to analyze and synthesize an eco-friendly method of water conservation, storage, and purification for the modern age, perhaps one that relies on the wisdom of our ancestors.

References

- K. SHADANANAN NAIR. Role of water in the development of civilization in India—a review of ancient literature, traditional practices and beliefs. Proceedings of the UNESCO/ IAHS/ WHA symposium held in Rome. December 2003).

- Festivals in the month of Aadi. Hindu; JULY 13, 2007 00:00 IST. UPDATED: SEPTEMBER 29, 2016 02:03 2.

- Mettur Dam”. Wiki Pedia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-

- Grand Anicut(Kallanai)and associated farming system in Cauvery Delta Zone of Tamil Nadu Submitted by Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore 641 003 & M.S.Swaminathan Research Foundation Chennai – 600 113.2008. (Ula literatures viz.,Vikramacholan Ula and Kulothunga Cholan Ula state that Karikala Cholan built Kallanai by deploying the men from defeated kingdoms.)

- Guhan S. “The Cauvery River Dispute –Towards Reconciliation”. Frontline, Madras, India(1993).

- “Rains, Floods kills 269 in Tamil Nadu, 54 in Andhra Pradesh”. The New Indian Express. 3 December 2015

- Shreya Biswas. News Remembering 2015 Chennai flood: How the city suffered and survived heavy rains 2 years back. India today, November 4, 2017.

DHASTAGIR SULTAN SHERIFF, PhD, is a retired professor from the faculty of medicine at Benghazi University in Libya. He now lives in India and is an expert in medical biochemistry. He is the author of a textbook titled Medical Biochemistry, five monographs, and over 150 research publications.