Victoria Lim

Iowa City, Iowa, United States

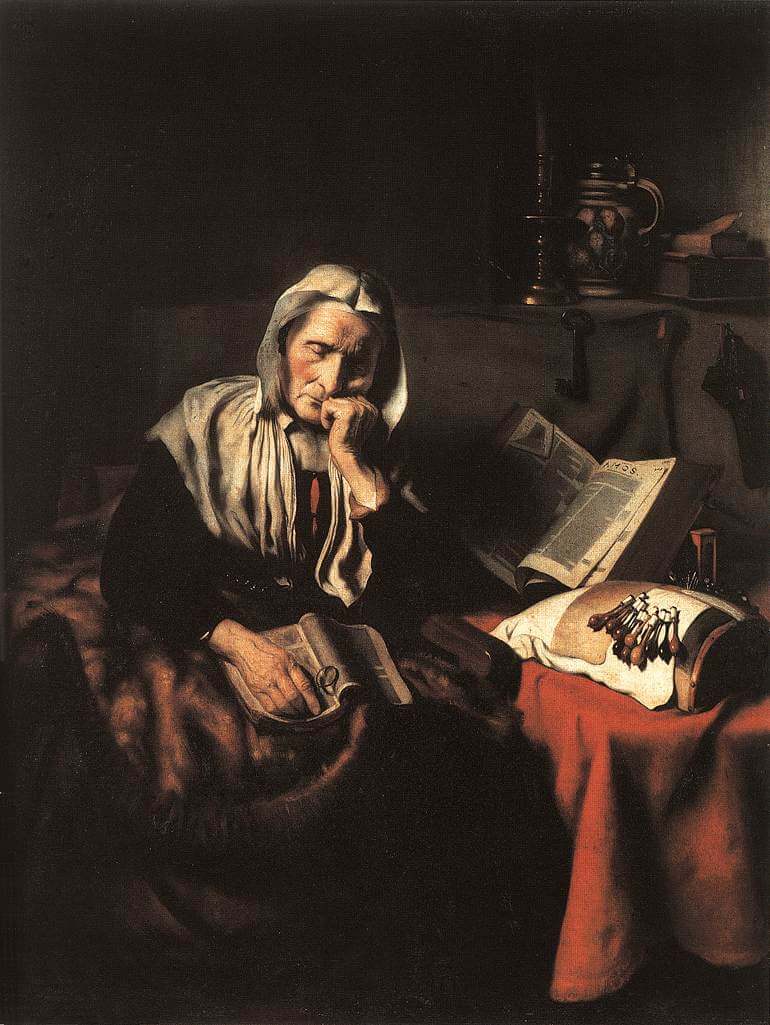

Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693)

One early morning I was paged to see an eighty-five-year-old patient in the dialysis unit with low blood pressure. I learned that she had diabetes, hypertension, and diffuse atherosclerosis. In the past decade she had undergone four major surgeries for blocked arteries and had suffered two strokes. For the past year she had been on hemodialysis for chronic kidney failure and was confined to a nursing home. During the last few months, she had been taken to the emergency department many times for deteriorating mental status, falls, and low blood sugar.

She was a small woman, eyes closed and moaning, about to fall off the recliner. As we pulled her up a bit she let out a series of cries. The move must have elicited pain, but where? We did not know and she was unable to tell us. Her face was ravaged by age and sickness; her body shrunken, fragile and, I thought, unfixable. I sensed the naked truth of aging and the unforgiving nature of time; I felt vulnerable myself. Not wanting to torture her further, I asked for a family meeting, which did not happen because she was admitted to the hospital the next day.

I was called to see her a second time when she had just been discharged from the hospital. In the three months since I had first seen her, she had been hospitalized almost continuously. Consultants from nephrology, neurology, cardiology, interventional radiology, and endocrinology had taken care of her. Extensive neurologic tests including an MRI demonstrated old infarcts and cerebral atrophy. She had received a cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and stent placement. While all these tests were proceeding, she developed a clot in her dialysis catheter and was sent to radiology for declotting. During that procedure, she had a cardiac arrest; she was resuscitated and the procedure was stopped. After that she developed infections, her mental status deteriorated further; and she became severely demented.

I met with her son and daughter and agreed to continue treatment for another month. By that time, if her condition had not improved, we would stop dialysis and seek hospice care. A few days later, she was seen in the emergency department for yet another fall. While a head CT and spine x-ray showed no bleeding or fracture, she was obtunded and did not follow commands. The son asked for further imaging studies. I gently disagreed and told him that even if something was found, she would not survive surgery. I then added that if they were ready, we could stop dialysis treatment and pursue hospice comfort care. I was convinced that further intervention would only aggravate her suffering; I offered this advice with trepidation and humility. She died one week later in the palliative care unit in our hospital—a home-like environment, surrounded by family members. Except for a peripheral intravenous line, there were no tubes, monitors, or other equipment. Upon learning of her death, I phoned the son to ask if his family had any regrets about the decision. The answer was an unequivocal “no,” and I sensed relief in his tone and words.

Why did the healthcare system prolong the suffering of this elderly woman with aggressive treatments when there was no chance of getting better? Her body and mind were burned out and broken. While she yearned for rest, the healthcare system kept pulling her back to cleanse her blood and de-clog her arteries. Are these futile procedures the last rites needed to enter the gates of heaven? Who benefited from her extended intensive care? Certainly not the patient, who moaned and cried during every dialysis session. Neither did it make any difference to her family, who lived a relatively undisturbed life during her illness. It was the nursing home staff who transported her to and from the hospital, eased her pain, and took care of her after each fall. This patient paraded through a long line of seasoned nephrologists during her illness; none took the initiative to consider stopping dialysis, indicating that this was the prevailing practice norm. Such action then led to all the other costly, redundant, and painful interventions, procedures, and resuscitations.

Why was this woman not allowed to “go gently into that good night”? There are many contributing factors. First, she did not have a medical directive, which would have stated her wishes when she was no longer able to make decisions for herself. Second, she did not have a primary care physician who took charge of coordinating all aspects of her treatment. Her care was fragmented and involved too many specialists who were focused on a particular organ system, even though the person who possessed those organs was irreversibly failing. Third, her family was minimally involved except for demanding that everything be done, including cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. In discussing treatment choices for this patient, “stop treatment in exchange for comfort care” was not presented as an option. In the setting of chronic illnesses, halting treatment takes more effort and time than staying the course.

Many physicians and patients in this country approach medical treatment without having to worry about expenditure because it is charged to a third party system. As healthcare expenses spiral unsustainably upward, judgment in spending is critical, especially when there is no expected outcome that will prolong life or relieve suffering. This is a topic that needs to be wrestled with by all facets of the medical profession.

VICTORIA LIM, MD, is a nephrologist who has worked at the University of Chicago and at the University of Iowa. She has retired from active practice and lives in Iowa City.

Leave a Reply