Vincent de Luise

New Haven, Connecticut, United States

“You need color to make music come alive. Without color, music is dead.” — Sergei Rachmaninoff

|

| Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) |

There are piano concertos and then there are Piano Concertos. While favorites include the Tchaikovsky First, Mozart’s Twenty-first, the Beethoven Fifth (“Emperor”), and the first concertos of Brahms and Chopin, to many listeners the most beloved of all is the Rachmaninoff Second, with its lush romanticism and unforgettable melodies. Lest one think that the creative process in music is always seamless and linear, the genesis of the Rachmaninoff second piano concerto runs counter to that myth, with several fits and starts during its gestation, and if not for a serendipitous partnering of composer and physician, this masterpiece would likely never have seen the light of day.

Any search for the musical expression of passion naturally leads to Rachmaninoff. While his earliest compositional efforts display the influence of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, he soon found his own muse, composing melodies with an extraordinary lyricism and a rich orchestral tonal palette. The piano figures prominently in Rachmaninoff”s output, and through his own skills as a performer, he fully explored the expressive possibilities of the instrument.1 Possessed of a formidable technique and an eidetic memory, Rachmaninoff was able to recall whole symphonic movements decades after learning them. Yet he was self-effacing to a fault, and often acknowledged an inspirational debt to prior masters, writing that “if you are a composer, you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and their ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my interpretations. You need color to make music come alive. Without color, music is dead.” 2

The legacy of Rachmaninoff’s piano works, especially the concerti, has been far greater than that of his symphonies. The premiere of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony in 1897 brought the anxious and self-doubting twenty four-year old composer nothing but negative reception and heartache, so much so that he became an insomniac, lost his appetite and spiraled into melancholia.1 Ironically, one of his harshest critics was his older friend, and a member of the famous “Russian Five,” the composer César Cui, who compared Rachmaninoff’s first symphony to “the ten plagues of Egypt,” and suggested that he had studied in a “conservatory in hell.”1

That was not exactly an encouraging assessment, and the scathing comment could easily have been the end of Rachmaninoff’s career. Although he continued to conduct, concertize and travel, he was unable to compose anything of substance for three years, until his aunt recommended he seek out the opinion of a music-loving physician, Dr. Nikolai Dahl, who had successfully treated her for a psycho-somatic ailment.3,4 It was to be a doctor who would rebuild Rachmaninoff’s self-confidence, remove his writer’s block, and rekindle his creative spark.

|

| Nikolai Dahl (1860-1939) |

Nikolai Vladimirovich Dahl was a prominent Moscow neurologist and psychiatrist, as well as an excellent amateur violist.4 In the late 1880s, he traveled to Paris to study with the legendary professor Jean-Martin Charcot at the Hospital Salpêtrière. Charcot was at that time investigating hypnotherapy as a modality in the management of dystonia.4 Hypnosis had been used since the work of Friedrich Anton Mesmer in the early 1800s, and by the turn of the last century, had become accepted as a therapeutic tool.4 Freud was using hypnosis to produce “catharsis” in his patients from their childhood traumas; Dahl’s approach would be to use it as a form of positive talk therapy.

Beginning in January 1900, in intensive daily sessions over four months, Dahl worked with Rachmaninoff, using hypnotherapy and post-hypnotic suggestion to improve his sleep and appetite, brighten his mood, and break him of his compositional roadblocks.4 “You will begin to write your next concerto,” Dahl urged Rachmaninoff, who later recalled his many sessions with the physician. “I heard the same hypnotic formula repeated day after day, while I lay half asleep in the armchair in Dahl’s study. Dahl would say to me, “You WILL write a Concerto. . . . You WILL work with great facility. . . . It WILL be excellent….” The strategy worked, as Rachmaninoff went on to reminisce, “….although it may sound incredible, this cure really helped me… By autumn, I had finished two movements of the Concerto…”1,3

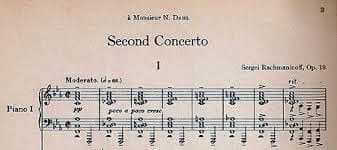

Rachmaninoff had sufficiently recovered by April to travel to the Crimea and Italy. While he had sketched the second and third movements of his second piano concerto by October, it took another year to finish the work. In gratitude, he dedicated the concerto to his treating physician: the autograph manuscript is engraved, “A Monsieur N. Dahl.”3,5

|

| Frontispiece of the second piano concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff, with its dedication, “a Monsieur N. Dahl” |

Five days before showcasing the work, Rachmaninoff suffered a panic attack, convinced once again that he had produced an inferior composition, but the fabulous response he received at the premiere on November 9, 1901, where he himself was soloist (and his cousin Alexander Siloti the conductor), convinced him otherwise.6 The concerto is suffused with a trove of exquisite melodic motifs, with Rachmaninoff channeling his Romantic forebears – Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky. Since its premiere, the Second Concerto has remained one of the most popular compositions in the repertoire, and its melodies grace television and film, even though Rachmaninoff himself never wrote a cinematic score.

As musicologist James Keller insightfully explains, “The first movement rises out of mysterious depths, but quickly lets loose the first of many striking themes. It is surely a virtuoso concerto, yet Rachmaninoff disguised the virtuoso element, as most of the melodies in this movement are entrusted to the orchestra rather than to the solo piano. The second movement, in contrast, is a tender meditation between piano and orchestra, with both partners offering melodic ideas, and with Rachmaninoff looking backwards to the nineteenth century, drawing its main theme from one of his earlier piano compositions.”7 The principal theme of the finale comes from a sacred choral work that Rachmaninoff had written in 1893, but it is the second theme of this movement that has captured the hearts of music-lovers everywhere.

Dahl passed away in 1939 after a distinguished career in neurology and psychiatry. Rachmaninoff not only completed his second piano concerto but two more besides, and dozens of other magnificent compositions in the ensuing four decades of his life. There had long been speculation that Rachmaninoff, six-foot three and with long slender fingers that could span a twelfth on the piano, may have had either Marfan syndrome or acromegaly, however no autopsy was performed and neither condition has ever been proven. What is known is that he suffered from chronic low back pain, neuralgias, and hypertension, and towards the end of his life, after living in New York City and Switzerland, moved to southern California upon the recommendation of his Swiss physicians.

Rachmaninoff died of metastatic melanoma on March 28, 1943, in Beverly Hills, California, a few days before his seventieth birthday. One of his own favorite compositions, the ineffable Vespers (All-Night Vigil) was sung at his funeral. He is buried at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, fittingly near many other notables in the world of music and the arts.

References

- Norris, G. Rachmaninoff. (Master Musicians Series). New York. Schirmer, 1994, pp. 113-120.

- Rachmaninoff Society of Great Britain, Newsletter 52; October, 2002

- Bertenson, S. and Leyda J. Rachmaninoff. A Lifetime in Music. New York. New York University Press. 1956.

- Niels, E. “Nikolai Dahl’s Cure – Good Luck or Good Practicing?” Rachmaninoff.org Oct 2014

- Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto no. 2. Frontispiece. https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi2448.htm

- Steinberg, M. Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto no. 2, San Francisco Symphony Orchestra program notes.

- Keller, J. Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto no. 2, New York Philharmonic program notes.

VINCENT P. DE LUISE, MD, FACS, is an assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Yale University School of Medicine, and adjunct clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medical College, where he also serves on the Music and Medicine Initiative Advisory Board. He is a senior honor recipient of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and physician program co-chair of the Connecticut Society of Eye Physicians. A clarinetist, Dr. de Luise is president of the Connecticut Summer Opera Foundation, organized the Connecticut Mozart Festival in the composer’s bicentenary death year, co-founded the annual classical music recital at the annual meeting of the AAO, and writes frequently about music and the arts.

Leave a Reply