Magdalena Grassmann

Bialystok, Poland

Eva Niklinska

Nashville, Tennessee, USA

|

|

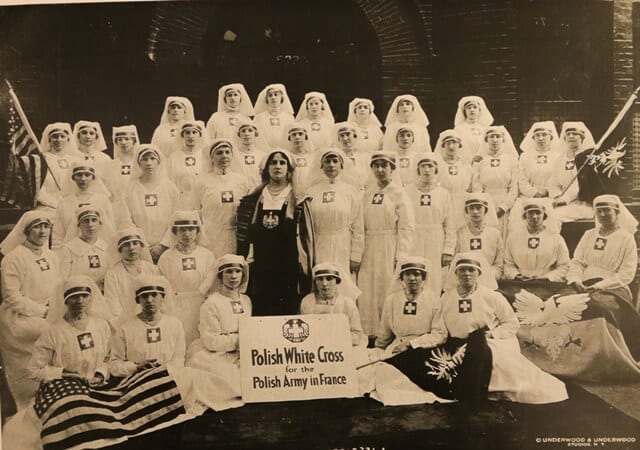

Helena Paderewska with the nurses of The Polish White Cross, 1918 |

|

| Polish White Cross Symbol |

Polish medical heritage in the United States has a long history built on the efforts of Polish physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in many American universities, hospitals, and private practices. It advanced the frontiers of science and addressed medical needs during World War I. Although Poland was not independent at that time, Polish soldiers fought on many fronts during World War I. It was the initiative of Poles in America that gave rise to a program supporting Polish soldiers and families in 1918, namely the Polish White Cross (PWC).

The visionary person behind the idea of the Polish White Cross was Helena Paderewska, wife of world-renowned Polish pianist, composer, and politician Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The Paderewskis were great philanthropists, best known for their dedicated activism towards the creation of the independent Polish state in the early twentieth century. Paderewska’s idea was to establish a Polish arm of the International Red Cross. Yet despite the efforts of Polish soldiers during the war, the Red Cross rejected the idea because Poland was not politically independent but under Russian, Prussian, and Austrian occupation.

This obstacle did not deter the determined philanthropists. On January 14, 1918, at the Gotham Hotel in New York, Ignacy and Helena Paderewski, Henry Davison (Chairman of the War Council of the American Red Cross), Col. A.D. Le Pan, and representatives of the Polish community officially established the Polish White Cross. It was an organization close in name and purpose to the Red Cross, but distinguished by a white cross on a red background, the opposite to its Red Cross counterpart. Helena Paderewska was elected as first president of the new organization and legal matters were charged to Dr. Frank Lenart.

The headquarters of the Polish White Cross were first in New York and later in Chicago. Soon the organization spread to Canada, sustained by strong affiliations with Polish churches in both countries. Every Polish woman in the United States or Canada fifteen years of age or older could be a member of the PWC and take on the responsibility of caring for Polish soldiers worldwide.

Helping wounded soldiers

The mission of the organization was to support Polish soldiers in America and Europe, especially those fighting on the World War I front such as the Polish army in France. PWC’s impact was profound. It provided medical assistance on the battlefields and in the camps. It covered all facets of military life, from founding and staffing field hospitals and rehabilitation centers, to providing cultural and educational services. Each Polish soldier fighting in France received full medical attention, a provision of clothes and cigarettes, and biannual holiday packages for Easter and Christmas.

The Polish White Cross had a huge influence. It supplied Niagara-on-the-Lake, the field hospital for Polish volunteer soldiers in Canada, with equipment and medicines. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, it immediately sent medicine, dressings, and additional equipment, as well as fruit and underwear. It also sent two nurses, American women of Polish descent, to work in the hospital until the end of the epidemic.

Training of nurses of the Polish White Cross

The training of competent and compassionate nurses was spearheaded by Helena Paderewska herself. In June of 1918, the first training program was organized in New York under the direction of Professor Boleslaw Lapowski. The course combined lectures given at the Felicjan Sisters’cloister and hands-on clinical experience at three New York hospitals: New York State, St. Francis, and St. Vincent. On July 16, 1918, the program graduated forty-two nurses who would travel to serve at field hospitals across Europe, including in Le Perray, France. The quality care provided by these women was invaluable.

Poland regained independence on November 11, 1918, at the end of the war. The PWC field hospitals were dismantled. Eighteen nurses returned to the United States and twelve nurses joined the American Red Cross in Poland to work with the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

|

|

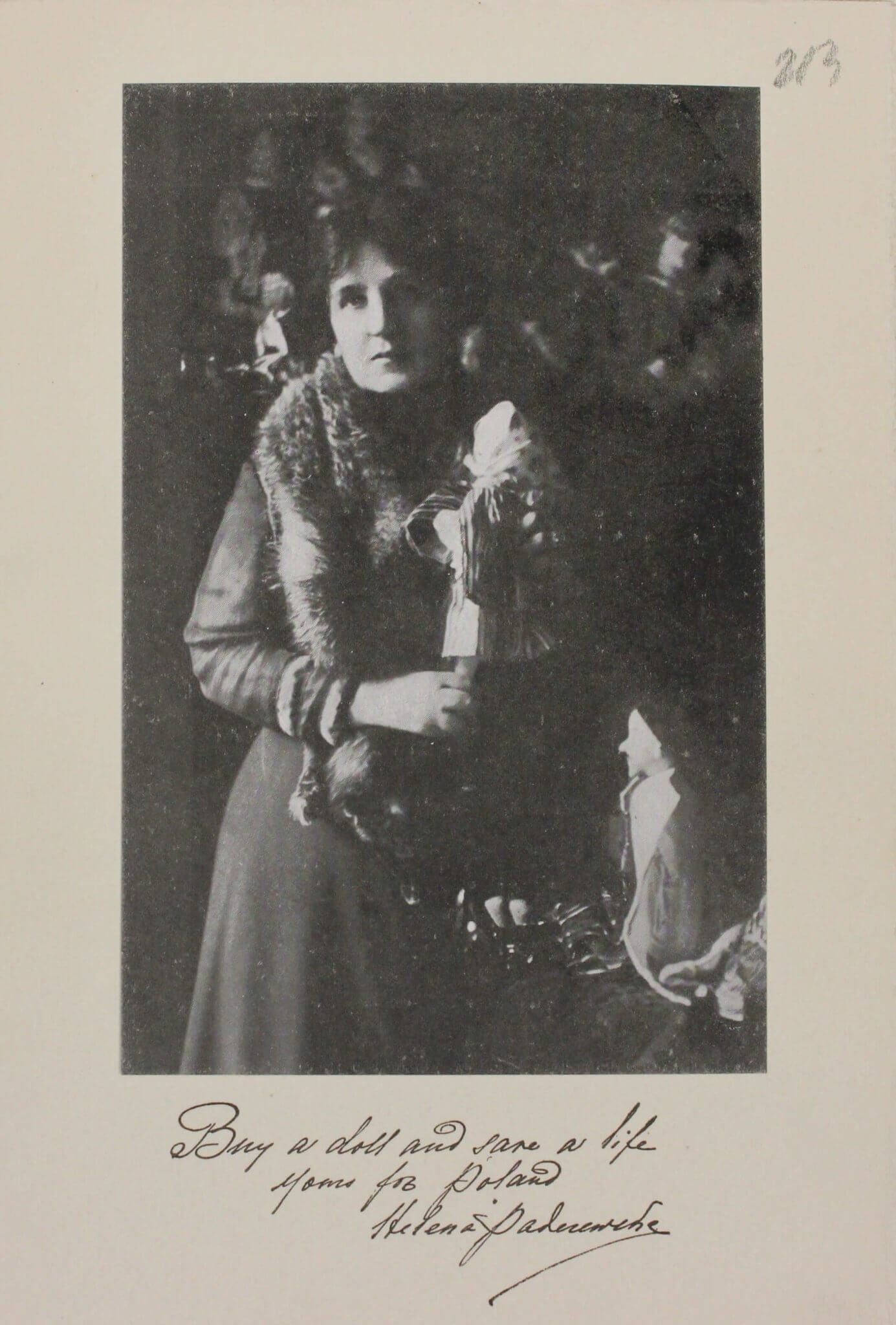

| Helena Paderewska propagating the action” Buy a doll and save a life,” 1918 | Paderewska’s Dolls from the Polish Museum in Chicago. Credit: R. Muskala |

Buy a doll and save a life – Paderewska’s Dolls

Large monetary contributions were needed to support the workings of the PWC. Helena Paderewska’s dedication and ingenuity helped mobilize efforts such as charity events (including Ignacy Paderewski’s piano concerts) and the sale of Polish dolls at events in several cities. The tale of “Paderewska’s Dolls” began in 1915 when Paderewska visited the Polish Art Gallery of Stefania Lazarska in Paris. The gallery was full of the work of Polish artists: dolls representing regional Polish dress and intricate local history. Impressed by their beauty and connection to the culture she held so dear, Helena ordered 1,000 of them to be sent to New York. The most popular dolls in the United States were called Jas and Halka. Some of the dolls donned the dress of Polish White Cross nurses to propagate the idea of the new organization. Priced at two to three hundred dollars each, the dolls helped PWC efforts to support Polish troops. Today the historic and beautiful “Paderewska Dolls” can be seen in the Polish Museum in Chicago.

|

| Operation Room in The White Cross Hospital in Warsaw, 1929 |

Helping the victims of war

The monetary needs of the PWC were supported by donations from Polish communities in the United States and Canada, as well as by private and public donors including the American Red Cross. There were also donations of medical supplies, clothes, and food. During the month of September 1919 alone, ninety-one train containers were sent to Poland and France. During the war, Polish soldiers received twelve ambulances and two cars from the American and Canadian Red Cross. Over 200,000 persons were provided clothes and shoes.

After gaining independence in 1918, Poland was left in poverty, devastated by the war. The mission of the PWC was redirected from supporting war efforts to supporting the independent, post-war Polish nation. The PWC’s effort flourished at its main collection site at St. Albert’s Church in Chicago, under pastor Kazimierz Gronkowski. Polonia’s generosity and the PWC’s sustained commitment allowed the organization to support many institutions in Poland, including a medical hospital for wounded soldiers in Warsaw at Dzielna Street, the Rehabilitation Center in Skolimowo, the Home for Orphans of War, the Elderly Home in Sulejowek, and many others.

After World War I, the PWC combined the efforts of over 228 organizations in Poland, including soup kitchens, sewing centers, laundries, literacy courses for writing and reading, training for blind veterans, libraries, schools and nurseries, a hospital, and two rehabilitation centers. Aside from coordinating these organizations, the PWC was in charge of distributing US donations to Polish veterans and their families. In the United States, the PWC also helped returning Polish veterans receive medical care in hospitals in Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and New York.

Polish White Cross moves to Poland

The Polish White Cross in the United States functioned until 1919 at headquarters in New York City and later in Chicago—connected with the National Polish Department. The formal end of its official activity was January 1919. Subsequent actions such as collecting donations for citizens in Poland were continued by the Polish Women’s Rescue Service established at the National Polish Department. The liquidation of the Polish White Cross in America was undoubtedly due to the Paderewski’s trip to Poland, where on November 23, 1918, he took office as prime minister and minister of foreign affairs of independent Poland. No one else was available to continue with such energy the activities of this organization in America. The statutory activities of the Polish White Cross were transferred to Poland, where it operated until 1946.

The Polish White Cross was a beacon of hope for Polish soldiers and families, playing a powerful role in addressing their medical, cultural, and social needs. It was an extraordinary example of the patriotic and spiritual commitment of Poles in America to rebuilding the Polish nation in Europe.

References

- Archives of Polish Museum of America, Chicago, Polish White Cross, archival reference number 104.

- Archives of Modern Records in Poland, Warsaw, Archives of I.J. Paderewski, archival reference number 3876.

- Archives of Modern Records in Poland, Warsaw, Archives of I.J. Paderewski, archival reference number 3954.

- Archives of Modern Records in Poland, Warsaw, Archives of I.J. Paderewski, archival reference number 3861.

- Archives of Modern Records in Poland, Warsaw, Archives of I.J. Paderewski, archival reference number 3949.

- Archives of Modern Records in Poland, Warsaw, Archives of I.J. Paderewski, archival reference number 3906.

- Boydston, Jo Ann, ed. “Confidential Report of Conditions among the Poles in United States”. John Dewey. The middle works 1899-1924 11 (2008): 259-330.

- Brożek, Andrzej. Polish Americans 1854-1939. Warsaw: Interpress, 1985.

- Granacki, Victoria. “Ignacy Jan Paderewski. A pianist and his passion for Poland come to Chicago”. Social Sciences Framework 3.0: 162-184.

- Krynska, Elwira. Polski Biały Krzyż (1918-1961). Białystok, 2012.

- Nieweglowska, Aneta. Polski Biały Krzyż a wojsko (1919-1939). Toruń, 2005.

- Radzik, Tadeusz. “Działalność Polskiego Białego Krzyża i Sekcji Ratunkowej Polek w USA w latach 1918-1920”. Przegląd Polonijny (1) 1990.

- https://histmag.org/Inspiracje-zabawkarsko-polityczne-czyli-polska-lalka-a-sprawa-polska-15267/3

- http://french-cloth-dolls-encyclopedia.com/web/index.php/fr/articles?id=419

MAGDALENA GRASSMANN, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor of history of medicine and the head of the Independent Department of the History of Medicine and Pharmacy in Medical University of Bialystok in Poland. In 2011, she was appointed Director of the Museum of the History of Medicine and Pharmacy at the Medical University of Bialystok. Her research focuses on medical heritage and its role in society and culture and also the role of medical collections and museums and the history of medicine.

EVA NIKLINSKA is a medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Winter 2018 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply