JMS Pearce

Hull, England

On the bleak, rocky, windswept Yorkshire moors is the famous Brontës’ parsonage of St Michael and All Angels’ Church, Haworth. Here the celebrated Brontë sisters wrote their varied poetry and tales of romance, repressed passions, and frustrated love. This year (2017) marks 200 years since the birth of their brother, Patrick Branwell Brontë.

Their father, the Rev Patrick Brontë, curate and poet, had moved the family to the parsonage in 1820, a year before the mother Maria (née Branwell) died. There remained their one son and five daughters: Maria (1814), Elizabeth (1815), Charlotte (1816), Patrick Branwell (1817), Emily Jane (1818) and Anne (1820). In 1825, Maria, aged 11 and Elizabeth aged ten both died of tuberculosis.

Patrick Branwell Brontë (Fig 1) was a talented intelligent boy, with three adoring sisters who were later to be preoccupied with his sullied life. In youth he was an essayist, poet and artist. With sister Charlotte he devised a series of imaginary role-playing ventures, which involved his younger sisters Emily and Anne; they composed and acted plays and stories about their imaginary worlds. When aged 11, he began his own magazine, “Branwell’s Blackwood’s Magazine.” He also was trained as a painter by a reputable artist, William Robinson.

As an adult, his precocious boyhood talents became tarnished by his self-indulgencies which were to be his ruin. Ironically, the name Brontë derives from Bronte (Βροντης) who was the Cyclops goddess of thunder. Branwell’s decline came to haunt the Brontë story, in contrast to the astonishing literary achievements of his sisters. Unfortunately medical accounts of Branwell’s varied alcoholic and opiate induced symptoms are not easily obtained.1 Biographers’ observations2,3 are necessarily swayed by the lay ideas of Medicine prevalent at the time. The accuracy of later writers’ interpretation about his lifestyle and illness has been questioned and may have obscured the truth.4

Their father, the Rev Patrick Brontë, devoted himself to his aspirations for his talented son Branwell, but showed less interest and dedication to his surviving daughters. Emily was at times withdrawn, but also passionate, as shown in Wuthering Heights, in which the characters Heathcliff and Hindley Earnshaw may have mirrored features of Branwell. But she was often sympathetic to her brother’s decline into laudanum and drunkenness. Charlotte was more ambitious but intolerant; her character John Reed in Jane Eyre mirrors several aspects of Branwell. She much resented Branwell’s later alcoholism and wasted abilities. Arthur Huntingdon in Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall also resembles her brother Branwell. Like her sisters her writings were published under a pseudonym (Acton Bell) to mask the then unacceptable female gender of the author. Emily and Charlotte used the pseudonyms Ellis Bell and Currer Bell.

Relatively impecunious, the sisters were forced to work as governesses, work they hated; they decided to start a school at the parsonage, but this enterprise too failed. Branwell with his friend John Brown, sexton at the local church, was frequently found in the local Black Bull pub where he was known to be entertaining and witty; but it was probably here that his habituation to alcohol began. He also became a Freemason at the local lodge. Branwell sought work as a portrait painter and writer in Bradford in 1838. But only one year, later failing to prosper, he returned to Haworth in debt and with a developing dependence on drink. Branwell had been educated at home by his father who fostered his interest in art and literature. Many of his collected works, written with help from sister Charlotte, centred on politics, civil wars, and military campaigns. He submitted writings to Blackwood’s Magazine, covering poetry, drama and criticism.5 As teenagers and young adults, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë all wrote stories set in imaginary worlds. Glass Town, their original fictional land, was invented by the four together, though Branwell and Charlotte were mainly responsible. After 1831, Charlotte and Branwell branched out into Angria, an extension of Glass Town. The manuscripts, a series of disordered fragments, formed part of a longer chronicle by Branwell—under the pseudonym Henry Hastings—entitled Angria and the Angrians (1834 to 1839). Emily and Anne invented their own private world of Gondal,6 though the plays and stories of this imaginary land of Gondal have not survived.

Their varied writings showed the remarkably imaginative and creative powers of Branwell and his sisters.7 Branwell also played the organ in his father’s church, though his attempts to be a portrait painter failed. Showing early ambition Branwell sent poems and his translations of five of Horace’s Odes to Thomas De Quincey and to Hartley Coleridge (son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge) seeking opinions, and advice.

In 1840 Branwell took a position in the home of Robert Postlethwaite in Broughton in Furness, close to the famed literati of the Lake District. He was dismissed for disgraceful behaviour. In October 1840 he worked as assistant clerk on the new Leeds and Manchester Railway, and he sought out the Halifax literary circles of the Leyland brothers, and poets William Dearden, John Nicholson, and Thomas Crossley.8 He published his first poem, “Heaven and Earth”, in the Halifax Guardian, but was sacked from his railway post in 1842 because of his assistant’s bungled accounts. He published further poems and articles in local but reputable newspapers including The Guardian; many were under the pseudonym “Northangerland”.2

Following his sister Anne, in 1843 he worked as a tutor to Edmund, son of Reverend Edmund Robinson at Thorp Green, near York, and continued to write.9 But he had an affair with Edmund Robinson’s wife Lydia and was angrily dismissed. After Robinson’s death he was keen to marry Mrs Robinson, but was rejected.* Gravely disheartened, this episode was succeeded by further decline into drink, use of the opiate laudanum, and inevitably debt. Joseph Hardaker’s druggist shop supplied him with laudanum and the Haworth Black Bull and Bradford’s the George and Talbot’s hotel were habitual sources of his drink habit. He had bouts of disturbed behaviour, at times violence then periods of solitary withdrawal. At about this time Charlotte wrote to her close friend Ellen Nussey:

I wish I could say anything more favourable— but how can we be more comfortable so long as Branwell stays at home and degenerates instead of improving…he will not work— and at home he is a drain on every resource— an impediment to all happiness.

He lost appetite and weight and was thought to have bouts of delirium tremens according to Dr Wheelhouse of Haworth, but this has been disputed since he also had alcohol related fits:

The falls, the sudden excitement, followed by a lapse of consciousness, were charged to excessive drinking, and nothing else.

He was treated by Dr Wheelhouse, who according to Du Maurier suggested “abstention from alcohol, and nothing more.” Daphne du Maurier described the dilemma:9

It did not occur to Charlotte or any of the family that there was only one course to take, and that a consultation with the best medical opinion if the day was imperative if Branwell’s life and reason were to be saved. Charlotte and Emily had not hesitated to go to Manchester two years before to arrange about the operation for their father’s cataract, and after Branwell’s death, when Emily was dying and refused all treatment, Charlotte did at least write to a London specialist, asking for advice. No such action was taken for her brother. Dr Wheelhouse of Haworth suggested abstention from alcohol, and nothing more. The rapid loss of weight, the continuing cough, the appalling insomnia, were left to take their course. If Branwell was ill, he was ill through his own fault. There was no remedy.

This deterioration in health and lifestyle caused the family much distress and embarrassment and not a little angry frustration. He accidentally set fire to his bed, after which his father, Patrick insisted on sleeping in his room during his son’s horrific last days lest the drunk and outrageous Branwell did so gain or committed some terrible act of violence. Charlotte was particularly bitter about him and his wasted talents. Elizabeth Gaskell’s controversial biography (see Barker2) of Charlotte perhaps unkindly describes him as: “utterly selfish” and “self-indulgent.” She records:

Dec 31st, 1845

For the last three years of Branwell’s life, he took opium habitually, by way of stunning conscience; he drank moreover, whenever he could get the opportunity…He took opium because it made him forget for a time more effectively than drink…In procuring it he showed all the cunning of the opium-eater. He would steal out while the family were at church and manage to cajole the village druggist out of a lump… For some time before his death he had attacks of delirium tremens of the most frightful character…In the mornings young Brontë would saunter out, saying with a drunkard’s incontinence of speech, ‘The poor old man and I have had a terrible night of it; he does his best— the poor old man! But it’s all over with me.3

Within a year of Branwell’s death in September 1848, Emily, aged 30 died in December, and Anne aged 29 in May 1849, all three of tuberculosis. Charlotte died aged 38, in 1855, possibly of hyperemesis gravidarum. Father Patrick survived till 1861, aged 84.

In 1848, he collapsed outside his home and a physician examined him and diagnosed the final stages of pulmonary tuberculosis. It is possible this had been hidden by his alcoholism. Though denied by the article on the Brontë’s in the Dictionary of National Biography,6 a curious anecdote by Somerset Maugham relates that he died standing up:

Branwell proceeded to drink himself to death. When he knew the end was come, wanting to die standing, he insisted upon getting up. He had only been in bed a day. [His sister] Charlotte was so upset that she had to be led away, but her father, Anne and Emily looked on while he rose to his feet and after a struggle that lasted twenty minutes died, as he wished, standing.10

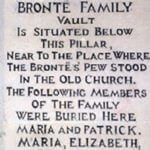

Branwell died at Haworth parsonage in September 1848, probably of tuberculosis aggravated by delirium tremens, 2 although his death certificate gives the cause as ‘chronic bronchitis-marasmus’. He was buried in the family vault beneath St. Michael and All Angels Church, Haworth (Fig 2) on 28 September, his literary aspirations largely unfulfilled. He was portrayed in the 1973 TV Series The Brontës of Haworth by Michael Kitchen, and by Adam Nagaitis in To Walk Invisible (2016), a BBC drama.

Comment

A small man with flaming red hair, Branwell was impulsive and quick-witted, and loved showing off in company. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that his careless disregard of others, his lack of perseverance in his work, and antisocial behaviour reflected both his abuse of drugs and the vagaries of family life he and his sisters experienced. Du Maurier commented sympathetically9:

and seeing his three sisters content in each other’s company – the happy circle which he had once completed – his bitterness turned inward, and he felt himself thrust out, abandoned, the veritable castaway who had haunted him as a child. And, like a child, he used a child’s weapons. If they withdrew their love from him, he must behave violently to win attention. Better be hated than ignored.

However, many of the myths2 surrounding their lives were related by Elizabeth Gaskell, including the isolation of Haworth, the harsh eccentricities of her father, and the Calvinistic melancholy of Aunt Branwell. Perhaps Branwell also displayed psychopathic/sociopathic traits. Like many other artists, musicians and writers through the ages, drugs and alcohol damaged his work and life. But an adverse effect is not inevitable since in other cases the underlying abilities and inspiration were not submerged. Beethoven, Schumann and Liszt were each reputed to take frequently alcohol to excess. Berlioz wrote: ‘Often I experience the most extraordinary impressions, of which nothing can give any idea… the effect is like that of opium.’ Chopin was rumoured to regularly take opium with a sugar cube to combat the symptoms of his tuberculosis. And in ST Coleridge and De Quincey opiates prompted fantastical visions and nurtured imaginative creations.

Charlotte’s frustrations are seen in the harsher views of Branwell written by Gaskell and Gérin. Branwell’s own comments, like those of Charlotte have to be treated with some circumspection since both were imaginative and prone to exaggeration. Francis Leyland, another biographer of the Brontë’s said that Branwell’s life had ‘been written by those who have some other object in view, and who, consequently, have not been studious to acquire a correct view of the circumstances of it.’

Notes

*Lydia Robinson inspired the name of the character Mrs. Robinson, who also has an affair with an educated lazy young man, in The Graduate (1963) and in the 1967 film.

References

- Gérin W. Branwell Brontë. Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, 1961.

- Barker J. The Brontës. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1994.

- Gaskell, E. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. 2 vols 1857. Oxford World’s Classics, Editor Angus Easson. OUP Oxford, 2009

- Rhodes P. Medical Appraisal of the Brontës. Brontë Society Transactions, 1972;16:2:101-109,

- Barnard R, Barnard L. A Brontë Encyclopedia. Oxford, Blackwell 2007

- Neufeldt, V A. Brontë, (Patrick) Branwell (1817–1848). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. OUP 2004.

- Glen H. The Cambridge Companion to the Brontës. Cambridge Univ Press, 2002. Edited by Glen

- Neufeldt V. A., The works of Patrick Branwell Brontë, 3 vols. New York: Garland Publishing 1997-99

- Du Maurier, Daphne. The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë, 1960; Little, Brown Book Group Electronic book text 2012. Imprint Virago Press Ltd

- Maugham W. Somerset. Great Novelists and Their Novels, Philadelphia, JC Winston Co. 1948.

JMS PEARCE M.D., F.R.C.P., Emeritus Consultant Neurologist Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 10, Issue 1 – Winter 2018

Leave a Reply