Katrina Genuis

Canada

Art found in hospitals generally has the aim of comforting the viewer. Presumably, ill patients or exhausted on-call physicians who amble past pastoral countryside scenes or watercolour flowers are reminded that despite their current difficultly there is great beauty in existence. But residences for the sick have not always contained artwork that is classically beautiful or straightforwardly consoling.

One of the most well-preserved pieces of early hospital art, the Isenheim Altarpiece, gruesomely depicts illness and death. It was created between 1512 and 1516 and according to art historian Arthur Burkhard “may be claimed as the most imposing monument of German painting and as the most moving and impressive series of religious paintings of the entire Middle Ages.”1 Max Beckmann, Emile Nolde, Jean-Marie Charcot, Walter Benjamin, and Pablo Picasso are some who have been transfixed by the altarpiece’s graphic depictions of suffering.2 Yet today many viewers may wonder what such blood-stained imagery could be doing in a hospital. What experience of this artwork is hidden from modern eyes?

The Altarpiece

The Isenheim Altarpiece is a composite work of sculptures by Nikolaus Hagenauer and paintings by Matthias Grünewald. It contains an impressive nineteen sculpted human figures, some paired with symbolic animals, and ten painted scenes, some spread across several wooden panels. Today the altarpiece can be viewed, dismantled from its original framework, at the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar, France. The original structure, placed on the high altar of the Antonite monastery church in Isenheim, was constructed like an adorned and multi-layered wardrobe that opened to three possible views.3 The Antonite monastic order specifically had the mandate of caring for the victims of the mysterious ailment St. Anthony’s Fire.2 Themes of suffering, disease, and end-of-life therefore pervade the altarpiece, mirroring the concerns of hospital patients.

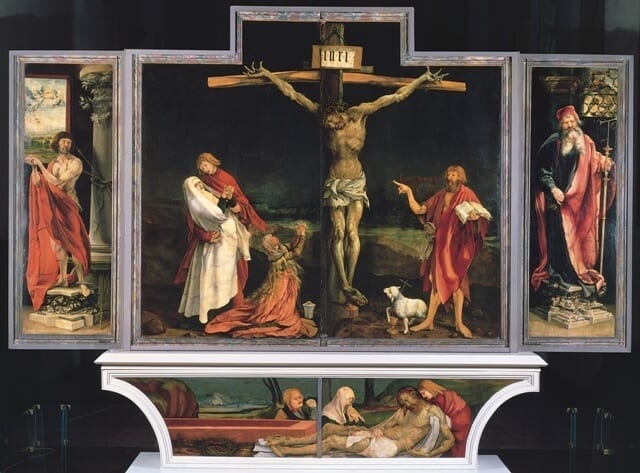

Most hospital viewers, however, would have only seen the altarpiece’s closed position (Figure 1); other views were revealed on certain liturgical feast days. In the closed position, the viewer saw the Crucifixion centrally, the Lamentation below, Saint Sebastian (protector from the black plague) on the left, and Saint Anthony (protector from St Anthony’s Fire) on the right. Demonic beings, such as the window-smashing creature above Saint Anthony, indicate a divine battle is at hand. Christ appears to be the victim in one of the most gruesome Crucifixion scenes in art history. His skin is marred with lesions, congealed blood dangles from his feet, and his lips are markedly cyanosed. Alongside the cross, sheet-white Mary is vividly syncopal (this common “swooning Mary” motif was later discouraged for being unscriptural).4 The intensity of agony in these hallowed religious figures is shocking to many modern museum visitors who wonder, all the more, how such images could comfort hospital patients.

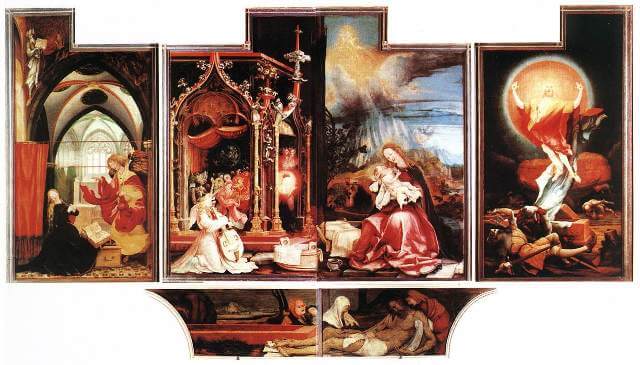

The second view (Figure 2), visible when the Crucifixion doors were opened, progressed through triumphant moments of the Christian narrative. The paintings depict (left to right) the Annunciation, the Concert of Angels, the Madonna and Child, and the Resurrection. Although thematically victorious, strangeness lurks. Note for example a peacock-feathered greenish creature amidst the angels (Figure 3). Ruth Mellinkoff in her book The Devil at Isenheim suggests that this is Satan, painted among the angels to depict deadly evil leeching into heavenly narratives.5 Yet Satan looks confused: he does not fathom the power of the Christ child—a foreshadowing (thinks Mellinkoff) of evil’s ultimate defeat.

On opening the final set of doors, the third view (Figure 4) displayed Hagenauer’s program of statues flanked by the painted images of the Meeting of St Anthony with Paul the Hermit (left) and the Temptation of Saint Anthony (right). The nightmarish Temptation scene recalls the battle motif: diseased demons physically assault Saint Anthony. It seems that Saint Anthony triumphs, however, because he is honored as the noble and gold-robed central sculpture, accompanied by the symbolic animal of his order, a pig. Given these descriptions of the diverse content of the work, it is helpful to explore the context of hospital viewers.

Historical and medical context

Patients at the monastery were reportedly led into the church to view the altarpiece at the beginning of their hospital admission and subsequently encouraged to participate in multiple daily services.2 It is difficult to imagine that relief could be found in art—be it beautiful or ugly—when one is in agonising pain and nearing demise; however, given sixteenth century views about the importance of near-death decisions and beliefs, patients in these moments may have been particularly receptive to religious imagery. Death protocols, such as the Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying) taught that in death there could also be triumph.6 Some art historians believe that triumph over sin and the promise of life beyond death is therefore the theme of the Isenheim Altarpiece.2,5

St. Anthony’s Fire, now identified as ergotism, was all too often fatal. The cause of ergotism, consumption of grains infected by the toxin-producing fungus, Claviceps purpurea, was not yet discovered. The toxins, ergot alkaloids, produced broad systemic effects ranging from as diarrhea or skin ulceration to gangrene and burning neuropathic pain.7 Antonite monks would examine patients for these symptoms before hospital admission; however, given the nonspecific initial presentation and the high prevalence of similarly-manifesting illnesses—syphilis, leprosy, and mercury poisoning for example—screening examinations were likely erroneous. Therapeutic strategies used in monastery hospitals involved providing physical comfort, nutrition, spiritual care, and herbal remedies (verbena and buckhorn plaintain are for example painted along the bottom of the St Anthony and Paul panel). Gangrenous limbs were reportedly amputated; however, as neither antibiotics nor effective anesthetic agents had been developed, these procedures were likely excruciating and frequently complicated by infection. In most cases the disease advanced, and often rapidly, causing dry gangrene, psychosis, seizures, and death.2

Several figures in the altarpiece display signs of these illnesses. The Christ figure bears graphic signs of systemic illness, perhaps St Anthony’s Fire. Disease also marks the bloated and pustule-covered demonic figure in the Temptation of Saint Anthony panel (Figure 5), and physicians such as Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, the “father of neurology,” have speculated about its diagnosis (Charcot concludes that disease is syphilis).8 As the painted signs of disease may have been inspired by the appearance of monastery patients, they hint at the diversity and severity of common hospital maladies.

The suffering of the sixteenth century Isenheim patients was representative of widespread turmoil in Northern European. Grünewald scholar Eugene Monick describes how the “last vestiges of the Middle Ages were drawing to an explosive close” as “war, famine, and disease” scourged the region. Interestingly, the cultural and economic situation was much different in the South, where the Renaissance was blooming. Italian artists such as Raphael were “attuned to the poetic mood of nature” and celebrated earthly life in their art. In the North, however, daily life was characterized by “medieval mysticism and populist suffering.”9 Patients facing the Isenheim Altarpiece, perhaps contemplating the frailty of their earthly existence, were embedded in this grim context.

Allopathic and homeopathic Art

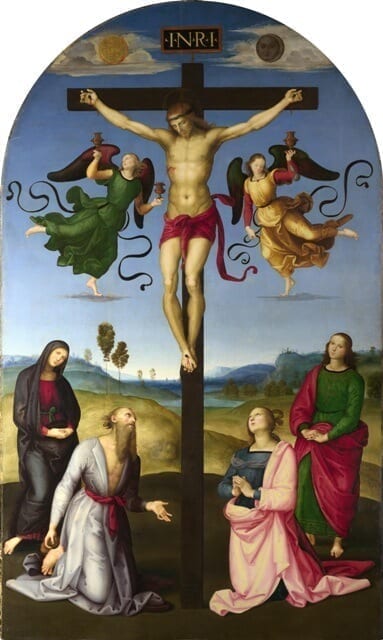

Having considered the setting of the Isenheim Altarpiece, it is not yet clear how an ill patient observing an image of suffering would find the experience meaningful. After all, some believe that psychological relief is achieved though “allopathic” art—that is, images that depict what is “other.” This approach, often taken in hospital settings, emphasizes the centrality of beauty in art. Inside fluorescent corridors, frames brim over with naturalistic imagery. Sick patients leaning on walkers trod past images of meadows, smiles, and new life. Raphael’s sixteenth century Mond Crucifixion, is an example of a Crucifixion scene that may have an allopathic effect (Figure 6). Allopathic approaches, which introduce the pastel and picturesque into circumstances of suffering and grief are not, however, universally comforting. In times of illness, “what may be most needed therapeutically is an image for expressing the grief, the depression, or the worthlessness and emptiness,” images that are “homeopathic.”9

Homeopathic art that depicts the dark corners of human experience may allow viewers to “get leverage on the shadows.” The imagery of affliction on the altarpiece acts as a “vessel for tortured, twisted sufferings” and affirms that victory can be experienced amidst immense difficulty. God’s defeat of the evil greenish Satan was not easy; its difficulty made it relatable. Perhaps when divine figures were depicted even in death as chiseled and serene, as in Rapheal’s Mond Crucifixion, the story of religion seemed to have nothing to do with the reality of human experience. The Isenheim Christ, by contrast, was made of diseased flesh and appeared to share human nature with the hospital patients: he contained “the opposites of beauty and ugliness” within himself. Pain was pictorially situated inside the divine story and, therefore, individuals who themselves experienced pain and suffering were not excluded from the story—nor from hope.9

This perspective is reminiscent of the thoughtful words penned by Rainer Maria Rilke—a renowned Austrian poet who once spent a day sitting in front of the Isenheim Altarpiece: “If it were possible for us to see a little further than our knowledge can reach, to see out a little farther over the outworks of our surmising, we should perhaps bear our griefs with greater confidence than our joys.”10 The Isenheim Altarpiece was created for hospital patients in moments of great grief. It has lasted centuries, not only impacting patients but also renowned scholars, artists, poets, and physicians. Instead of turning individuals away from their experience of suffering, the altarpiece gave an image to it. It related their circumstances to the divine, so providing the ultimate consolation: a reason to believe that suffering and death was not meaningless.

References

- Burkhard, Arthur. Matthias Grünewald: Personality and Accomplishment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936.

- Hayum, Andrée. The Isenheim Altarpiece: God’s Medicine and the Painter’s Vision. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Scheja, Georg, and Bert Koch. The Isenheim Altarpiece. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1971.

- Penny, Nicholas. The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings: Volume I. National Gallery Catalogues. London: National Gallery Company, 2004.

- Mellinkoff, Ruth. The Devil at Isenheim. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- Beaty, Nancy. Craft of Dying: The Literary Tradition of the “Ars Moriendi” in England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Schumann, G. L. “Ergot.” The Plant Health Instructor, 2000.

- Charcot, Jean-Martin, and Paul Richer. Les Difformes Et Les Malades Dans L’Art. Paris: Lecrosnier et Babé, 1889.

- Monick, Eugene and David Miller. Evil, Sexuality, and Disease in Grünewald’s Body of Christ. Dallas: Spring Publications, 1993.

- Rilke, Rainer M. Letters to a Young Poet. Translated by Karl W Maurer. London: Euston Press, 1943.

KATRINA GENUIS is a medical resident, specializing in Anesthesiology at the University of British Columbia, Canada. She is currently spending a year away from her residency to pursue an interdisciplinary Master of Letters degree at the University of Saint Andrews, Scotland, where she is researching how physical pain has been represented in visual art and literature, and how artistic perspectives can contribute to the care of patients experiencing chronic pain.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 9, Issue 3 – Summer 2017

Leave a Reply