Grant Gillett

Robin Hankey

Otago, New Zealand

|

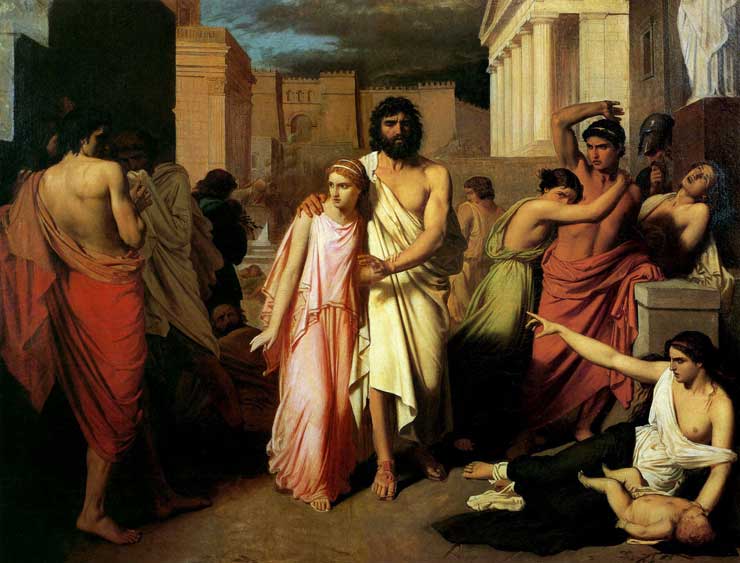

| Antigone Leads Oedipus out of Thebes Charles François Jalabert Musée des Beaux Arts, Marseilles, France |

Suicide has been a recurring human tragedy for as long as human affairs have been recorded. The principal suicide in Antigone does not at first pass seem relevant to the twentieth century, as it arises in the context of a judicial death penalty in a despotic state. Antigone’s suicide, however, has characteristics in common with the suicides of young people today. It expresses a devotion to certain ideals focused on her religion and family and shows many of the cardinal danger signs for imminent suicide. For that reason, any lessons we can learn about suicide from Antigone are timeless and should be writ large in our understanding of its terrible grip on us.

First, Antigone is deeply committed to her religious beliefs, and the dealings between her family and the gods mean that she inhabits a world in which suicide has meanings that obscure its awful finality and tragic waste.

Second, she is a young woman who has lost all that she really holds dear in her life. She is uprooted in her own home city, alone, can see no future for herself, takes no pleasure in her present life, is grieving terribly, and has lost the myths and meanings from which she might weave a fabric of value to sustain her in the face of the challenges that beset her. In the full flush of youth, she feels things intensely and lacks the experience of life that would otherwise equip her to deal with her emotional traumata. These are all familiar factors to those who deal with suicide as part of their clinical life, and they set off alarm bells. Thus Antigone allows us to explore, in the variety of suicides with which it deals, motifs with enduring relevance and forces that rend the fabric of our collective human soul in ways that are sometimes overlooked in medical literature.

Philosophical suicide is often a simple affair: an individual takes a rational decision that the value of life is outweighed by pain and distress and decides to end it all. But the social and clinical picture is not nearly as straightforward.

The phenomenon of political suicide is increasingly part of our news in various parts of the world. These are young people, often deeply religious, usually in a society where they are marginalized or oppressed. In this relatively helpless position a dramatic statement has to be made and we have one contemporary counterpart of Antigone’s suicide.

The major association with completed suicide in clinical life is clinical depression, but it often occurs not just as a constitutional problem but in association with triggering factors in the life of the person concerned including such as disruption of a valued relationship, loss of one’s immediate social group or a familiar social, cultural, and religious order.

Suicide is remarkably common in the tragedies of Sophocles, occurring in four of his seven extant plays (whereas there are no suicides at all in the extant plays of his older contemporary Aeschylus). In Antigone, no fewer than three characters kill themselves, and it is a revealing study of different types of suicide.

Antigone starts at a time of crisis in the city of Thebes and its ruling family. The young king Eteocles has died at the hand of his brother Polyneices, who had led the attacking army. Now, following the death of Eteocles, their uncle Creon (Jocasta’s brother) has become king and has proclaimed that Eteocles shall be buried with all honor, but Polyneices shall remain unburied outside the city as a traitor. Their teenage sisters are Antigone and Ismene, also children of the incestuous marriage of Oedipus and Jocasta.

Antigone reveals herself as strong-willed, uncompromising, and idealistic: she has already made her decision to defy the proclamation. She has no fear of death. She is ready to die rather than live in dishonor since she sees it as her religious duty, in accordance with the unwritten laws of the gods, to bury her brother.

Soon after we hear from a sentry that the corpse of the “traitor” Polyneices has been given the minimum symbolic burial of a covering of dust. The sentry returns with Antigone who is utterly defiant and unbowed. She is devoted to the dead members of her family and the higher calling of the gods, rather than to the living. Ismene, her sister, is treated with crushing contempt, and Haemon, her fiancé, takes second place to her devotion to her dead brother. Given her commitments, it is understandable that very soon the ominous events take shape and, even though Haemon is Creon’s son, Creon himself is not moved.

Haemon arrives to plead with his father to change his mind. The debate becomes bitter and Creon tells Haemon that he will never marry Antigone while she is alive. Haemon replies “Then she must die – and dying destroy another” (line 751, tr. D. Grene in The complete Greek tragedies vol. II Sophocles, ed. D. Grene and R. Lattimore, Chicago University Press, 1992). This tormented young man wants to strike back and he rushes angrily from the stage, shouting to Creon that he will never set eyes upon his face again.

Antigone’s suicide is described by a messenger—the sentries broke in through into the burial cave and saw her hanging by the neck with a noose of silk or muslin from her own clothing. In the event, imprisoned in this cave on Creon’s orders (in effect, buried alive), she was eventually going to die by slow starvation and her suicide merely hastened an inevitable fate. However, from the start of the play, Antigone shows her readiness to die, to be with her brother and dead family and, despite his evident passion for her, her love for Haemon was a relatively slight thing compared with the pull of her unworldly emotional and spiritual ties.

Haemon’s suicide, by contrast, is more emotional, impulsive, and violent. He enters the cave, embraces Antigone’s body and, as Creon went in, calling to his son, “The boy glared at him with savage eyes, … drew his double-hilted sword …and drove it halfway in, into his ribs” (lines 1231–6). In Haemon’s final encounter with his father, we can therefore see a maelstrom of emotions any or all of which could have motivated his suicide.

The final suicide of the play, that of Haemon’s mother Eurydice, is just as tragic. She hears the fates of Antigone and Haemon, silently leaves the stage and, as Creon appears with the body of his son in his arms, another messenger brings news that Eurydice is dead, by her own hand. He describes how she killed herself, standing at the household altar and stabbing herself in the belly, and in her final words lamented the fates of both her sons (before the time of this play, her elder son Megareus had offered himself to death to save the city), cursing Creon, their father, for being the cause of both.

These three suicides—Antigone, Haemon, and Eurydice—all die in the course of a single set of events but for different reasons spanning the range of human experience. Antigone may have been depressed, “my heart was long since dead” (line 559), and locates herself emotionally as an abject progeny of a monstrous marriage. The other suicides show emotions of shame, self punishment, grief, and anger.

In every case the constellation of factors is often unstable and goes through transient phases where the risks of suicide are particularly high. What if Antigone had found significant comfort in the love and companionship of Haemon or Ismene? What if Creon had not provoked his son to the impulse which drove him to the tomb of Antigone and then to attack his own father as the cause of his grief and loss, an embodiment of the harsh and unrelenting cruelty that the world may seem to show to the young and passionate? Eurydice is devastated by losing her only surviving son. Each person has become a danger to himself or herself and others and is not of sound mind. For all these reasons, in healthcare settings, we intervene to stop the suicide, to interrupt the course of affairs until time and events can transform what looks intolerable. Antigone and many other Classical suicides demonstrate the myriad ways in which life may present a forbidding and cruel face but our traditional stance is that that mask should not recommend death which is, without exception, tragic especially in the young.

Politically motivated violence and self-destruction have some of the same elements—powerlessness, indignation, identification with a cause or set of values, and a heroic or demonstrative act designed to dramatize an intolerable situation. But even here one might question the ethical structure of that complex situation which catches a young person full of idealism and with developing life skills in a situation which they do not have the wisdom and experience to see any way out of apart from their violent act. The tragedy is not lessened but in fact intensified by the sense that we have woven a lethal web of forces, both psychic and political, and caught this person in a trap that has but one exit, an exit involving death and destruction not only for themselves but also for their victims (many of whom would count as innocent by almost any reckoning one cared to make). Despite this ethical stance, we can see in our play the nature of the complex forces that tend to this awful result, and, one hopes, by seeing, begin to understand how to defuse them.

The thought that to understand is to empower ourselves to do better in the face of this recurring tragedy embodies the kind of ethical attitude that fuels the Hippocratic endeavor and, in this area as in so many others engaging with human suffering, medicine has much to learn from wider and more ancient sources of knowledge.

GRANT GILLETT, FRSNZ, FRACS, MB ChB DPhil (Oxon), is a Professor of Biomedical Ethics at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He is a qualified neurosurgeon and also completed doctoral study in philosophy at the University of Oxford. For the last twenty-five years he has been researching and teaching in medical ethics, philosophy, and the philosophy of psychiatry. He has authored seven books and 300 research articles.

, MLitt (St. Andrews), is a former Senior Teaching Fellow at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He received his BA at the University of Oxford. His main research fields are Homer and Greek tragedy and he has taught widely in Greek and Roman literature and thought.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 4

Fall 2014 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply