W. Paul McKinney

Louisville, Kentucky, United States

|

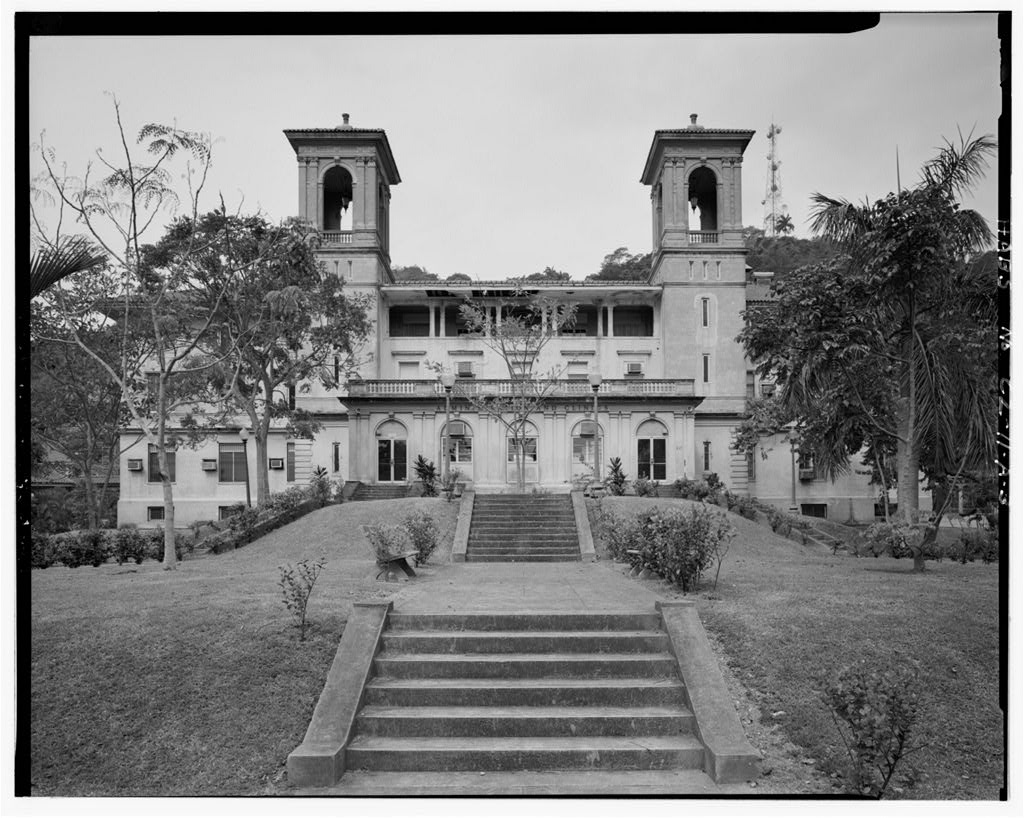

| West-facing view of Administration and Clinics Building, Gorgas Hospital, Ancon, former Canal Zone, Panama |

A man, a plan, a canal: Panama. This well-known palindrome describes the grand vision of Count Ferdinand de Lesseps for constructing, under the flag of France, a sea level canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in the late nineteenth century. Despite the best efforts of the French, the plan for a canal was abandoned, only to be revived by a team of American engineers who, with the support of a large workforce, created a successful path between the seas by 1914. Working somewhat behind the scenes but of equal importance were Dr. William Crawford Gorgas and his dedicated public health team who helped assure that tropical diseases would not prevent the completion of the grand project. Part of that effort was mobilized through the doctors, nurses and other health professionals who served at the main hospital on the isthmus later named in honor of Gorgas.

The hospital was not originated by Dr. Gorgas, however. Shortly after the arrival of Count de Lesseps in 1881, a small temporary medical facility called Strangers Hospital was built on the upper slope of Ancon Hill, near Panama City. It was replaced in 1882 by a much larger facility to serve the sick and injured employees of the French Canal Company. Constructed on the lower slope of the hill, the 700 bed L’Hopital Central du Panama was dedicated during a Pontifical Mass on September 17 of that year. Assisting the team of French doctors was a group of nuns from the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, whose devotion and selfless sacrifice to the sick and suffering remain legendary in Panama. A piece in the 1884 edition of the New York Tribune noted the following about Soeur Marie, the Mother Superior of Nursing Sisters: “Such women as she make a home out of a hospital and when all healing is unavailing they make even the scorched death of yellow fever easy, if such a thing can be.”1 The yellow fever ward at the hospital was said to have witnessed more yellow fever deaths than any other building still standing in the world at the time.2 These dedicated French doctors and nurses clearly set a high standard of performance for their successors to follow during its operation from 1882–89, after which the French canal construction effort was abandoned.1

In March 1904, the buildings of L’Hopital Central du Panama were acquired from the French by the US government through its Isthmian Canal Commission. Colonel William C. Gorgas was made the first sanitary officer of the Canal Zone and immediately sought to improve the aging and abandoned facility. One member of the new team, who had served in Cuba with Colonel Gorgas during his successful effort to rid Havana of yellow fever and who had survived the disease herself, was Chief Nurse Mary E. Hibbard. The intensive efforts of Hibbard and her colleagues allowed what was then designated Ancon Hospital to open for receipt of patients on July 15, 1905. While there were still outbreaks of yellow fever after the arrival of the Americans, Colonel Gorgas and his team of sanitarians essentially eliminated yellow fever from the canal construction area in 17 months, though malaria remained a problem for several more years. Years later, Dr Gorgas would write:

If we had had the hospital in 1884, we should probably have obtained no better results than the French did. At that time, they did not know that the [Aedes aegypti] mosquito transmitted yellow fever from man to man, nor did we.1

By 1914, some of the hospital’s buildings were over thirty years old and in need of replacement by a permanent facility. Construction of a newer hospital with five groups of ward buildings on the edge of Ancon Hill was begun in 1915 and completed in 1919. It was built in a modified Italian Renaissance style with Spanish vitrified red tile roofs unifying the array of structures. Wide corridors around all exposed sides of the wards provided protection from the tropical rain and intense sunlight, and loggias and continuous porches linked the wards to other buildings. Porches and all outside openings were screened with copper gauze to protect against the deadly mosquitoes. A separate isolation section was built to house all categories of infectious diseases. It was common to have 8–10 different infectious diseases represented in the unit on any given day.3

Many conveniences of the time were also added to the new buildings, such as passenger elevators, ice water supplied by a large refrigeration plant and modern plumbing with hot and cold running water. Magnificent shade trees from other countries, ornamental shrubs, flowering vines, and other rare and beautiful plants were added to create a virtual tropical botanical garden on site.3 As the fame of the new hospital spread, it was decided that the hospital should be rededicated in the name of William Crawford Gorgas; this was accomplished by a Joint Congressional Resolution on March 24, 1928. A further tribute to him was provided by Spanish American War veterans who placed a tablet in his honor at the hospital in 1938.1

In support of diagnostic and research needs, a freestanding laboratory building on site conducted bacteriologic, biochemical and pathologic studies. In keeping with its mission, autopsies were performed on about 60% of all deaths in the hospital;3 over 14,000 autopsies were done during the period 1904–1944.4 Internships and residencies in Internal Medicine, General Surgery, Urology, Ophthalmology, Diagnostic Roentgenology, and Pathology were active by 1947 and took advantage of the educational opportunities afforded by the unique case mix at the hospital.3

The intense interest in the study of tropical diseases at Gorgas Hospital and its affiliated sites, the Gorgas Memorial Laboratory and Gorgas Institute of Tropical Medicine attracted a number of brilliant and hard-working physician scientists to the hospital. Samuel T. Darling, who had a special interest in malaria, discovered and named a new infectious disease, histoplasmosis, based on his pathology studies.5 George H. Whipple, who came to the hospital in 1908 to work with Darling, focused his keen observations on the massive hemolysis of blackwater fever. He shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1934 for his later studies on the treatment of pernicious anemia with extracts of liver and described a disease he termed lipodystrophia intestinalis that was to bear his eponym.6 Brigadier General Theodore Lyster, who served as Chief of the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Clinic during his service in Panama from 1904-11, later developed a focus on the special needs of military pilots, creating the term flight surgeon and receiving the appellation “Father of Aviation Medicine.”7 In total, research studies on malaria, Chagas’ Disease, leishmaniasis, helminthic, rickettsial and viral diseases at the Gorgas sites resulted in the publication of over 600 scientific articles from 1930–69.8

After World War I era construction was completed, little changed at Gorgas Hospital until the early 1940s when expansion occurred in anticipation of its use for treating war casualties. The Canal Zone’s civilian population peaked at 57,390 in mid-1943 but dropped to under 45,000 by 1945; during that time, the average daily census dropped from over 1,000 to 925. After World War Two, the most significant new work on the hospital since canal construction days was ongoing from 1961-65, when a new eight-story main building was opened, providing modern facilities for surgery, radiology, physical therapy, intensive care, and pathology.1

The Torrijos-Carter Treaties of 1977, ratified by the US Senate in 1978, changed the role of Gorgas Hospital. In October 1979, all health care assets of the Panama Canal Company/Canal Zone Government, with the exception of a leprosarium that would be run by the Republic of Panama, were transferred to the US Army Medical Department.9 Because the Canal Zone would be reverting from US ownership back to Panama, the AMA’s Liaison Committee on Graduate Medical Education stated that its graduate medical education activities were no longer within their jurisdiction. Consequently, all residency training programs were phased out over three years.1

After a century of clinical and research activities in Panama, Gorgas Army Community Hospital, as it was designated in 1979, ended its official service to the US on October 1, 1997, in anticipation of the scheduled reversion of Panama Canal territories and facilities to the Republic of Panama by December 31, 1999. Since October 1999, it has been home to the Instituto Oncológico Nacional, Panama’s Ministry of Health and the Panama Supreme Court.2

Gorgas Hospital and its predecessor facility, the Ancon Hospital, were pivotal to the achievement of “one of the supreme human achievements of all time,” the completion of the Panama Canal.10 The hospital’s namesake was a legendary tropical medicine and public health expert who served as Chief Health Officer of the Panama Canal Zone from 1904 to 1914. Its wards served as the training ground over several decades for a host of medical interns and residents who learned from its patients the manifestations of tropical diseases, and through its halls passed a number of celebrated physician scientists. Throughout its history, the hospital never lost its primary focus on the care and comfort of the sick.2 Its physicians and nurses carried forward a tradition of professionalism and excellence in the advancement of medical knowledge established at the original site of L’Hopital Central du Panama in 1882. It is fitting, just over 100 years since the first passage of a ship through the canal in August 1914, to recognize the impact of the hospital and the heroic service to mankind provided by its entire affiliated staff.

References

- Samuel Taylor Darling Memorial Library Archives. US Army Academy of Health Sciences, Stimson Library. A century of medicine on Ancon, 1882-1982. http://cdm15290.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15290coll8/id/156. Accessed December 28, 2014.

- Chaves-Carballo E. Ancon Hospital: an American hospital during the construction of the Panama Canal,1904-1914. Mil Med 1999;164:725-730.

- Samuel Taylor Darling Memorial Library Archives. US Army Academy of Health Sciences, Stimson Library. Gorgas Hospital, Ancon, Canal Zone. http://cdm15290.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15290coll8/id/260/rec/7. Accessed December 28, 2014.

- Kean BH. The causes of death on the Isthmus of Panama; based on 14,304 autopsies performed at the Board of Health Laboratory, Gorgas Hospital, Ancon, Canal Zone, during the forty year period 1904-1944. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1946; 26:733-748.

- Darling, ST. The morphology of the parasite (Histoplasma capsulatum) and the lesions of histoplasmosis, a fatal disease of tropical America. J Exp Med 1909;11:515-531.

- National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs. George Hoyt Whipple. http://www.nap.edu/catalog /4961/biographical-memoirs.v66. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Craig SC. The life of Brigadier General Theodore C. Lyster. Aviat Space Environ Med 1994;65:1047-1053.

- Bremen, JG. Tropical diseases research in Panama: Historical perspectives and current opportunities. http://www.pitt.edu/~super7/18011-19001/18671.ppt. Accessed January 21, 2015.

- US Army Academy of Health Sciences, Stimson Library. Gorgas: 100 years of historic medical service. Southern Command News 1982;18:6-7. http://cdm15290.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15290coll8/id/268/rec/14. Accessed December 29, 2014.

- McCullough, D. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1978:613.

PAUL MCKINNEY, MD, is Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of Louisville’s School of Public Health and Information Sciences, where he serves as Director of the Center for Health Hazards Preparedness. He is also a part-time staff physician at the Robley Rex VA Medical Center, Louisville, KY. He received his MD degree from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas and completed his residency in Internal Medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a former Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer at the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Spring 2015 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply