Josephine Ensign

Seattle, United States

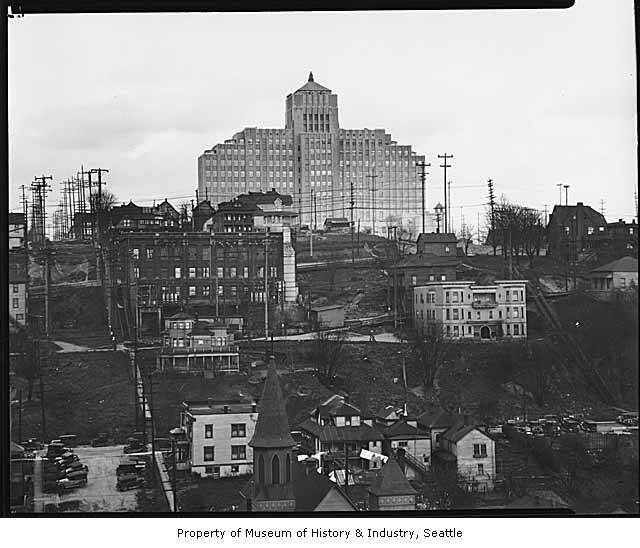

When Harborview Hospital in Seattle opened its doors to patients in 1931, advertising posters portrayed the striking fifteen-story Art Deco building as a shining beacon of light, the great cream-colored hope on the hill overlooking the small provincial town clinging to the shores of Puget Sound. “Above the brightness of the sun: Service” is what one poster proclaimed; in the bright halo behind the drawing of the hospital, were the smiling faces of a female nurse and her contented-looking (and either sleeping or comatose) male patient with a bandaged head.1

Harborview Hospital—King County’s main public charity care hospital—was built at the top of Profanity Hill, on the site of the former King County Courthouse and jail. Profanity Hill got its name from the steep set of over 100 slippery-when-wet wooden stairs connecting downtown Seattle to the Courthouse. One wonders if it also got its name from being at the top of the original Skid Road—now named Yelser Way—where in the early days of Seattle, freshly felled logs, mixed with a considerable number of public inebriates, skidded downhill together into the mudflats of Puget Sound.2 The term ‘skid road’ soon became synonymous with urban areas populated by homeless and marginalized people.

Counties are the oldest local government entites in the Pacific Northwest, and King County, which includes the City of Seattle, was formed by the Oregon Territorial legislature in 1852. From the beginning, the King County Commissioners were responsible for such things as constructing and maintaining public buildings, collecting taxes, and supporting indigents, paupers, ill, insane, and homeless people living in the county.3 Seattle, with its deep-water shoreline and rich natural resources, was built on the timber and shipping industries, which soon attracted thousands of mostly single and impoverished men to work as laborers. These industries, mixed with ready access to alcohol in the always ‘wet town,’ led to high rates of injuries. Serious burns came from the growing piles of sawdust alongside log or wood-framed houses heated by wood fire and coal. Then there were the numerous Wild West shootings and stabbings. As in the rest of the country at that time, wealthier families took care of ill or injured family members in their own homes, with physician home visits for difficult cases. The less fortunate relied on the charity of local physicians and whatever shelter they could arrange.

David Swinson ‘Doc’ Maynard, one of Seattle’s white pioneer settlers, was Seattle’s first physician and, in a sense, he opened King County’s first charity care hospital, an indirect precursor of Harborview Hospital. A colorful and compassionate man, Doc Maynard built and operated a two-bed wood-framed hospital facility in what was then called the Maynardtown district—now called Pioneer Square—a Red Light district full of saloons and ‘bawdyhouses.’ Although she had no formal training, Maynard’s second wife, Catherine, served as the hospital’s nurse. Their hospital, which opened in 1857, closed several years later, reportedly because Doc Maynard insisted on serving both Indian and white settlers. Also contributing to the hospital’s demise was Maynard’s dislike of turning away patients who could not pay for his services. Around this same time, Doc Maynard assumed care for King County’s first recorded public ward: Edward Moore, “a non-resident lunatic pauper and crippled man.”2 The unfortunate patient had to have his frostbitten toes amputated, and then once healed was given an early version of ‘Greyhound Therapy’ and shipped back East.

But the true roots of Harborview Hospital began in 1877 in the marshlands along the banks of the Duwamish River on the southern edge of Seattle. There, on an eighty-acre tract of fertile hops-growing land, the King County Commissioners built a two-story almshouse called the King County Poor Farm. They built the Poor Farm in order to fulfill their legislative mandate. Not wanting to run the Poor Farm themselves, they posted a newspaper advertisement asking for someone to take over operation of the King County Workhouse and Poor Farm, “to board, nurse, and care for the county poor.”4 In response, three stern-looking French-Canadian Sisters of Providence nurses arrived in Seattle by paddleboat from Portland, Oregon. The Sisters began operating the six-bed King County Hospital facility in early May 1877.

In their leather-bound patient ledgers, the Sisters of Providence recorded that their first patient was a 43-year-old man, a Norwegian laborer, Protestant, admitted on May 19 and died at the hospital six weeks later. The Sisters carefully noted whether or not their patients were Catholic, and in their chronicles recorded details of baptisms and deathbed conversions to Catholicism of their patients. The hospital run by the Sisters of Providence had a high patient mortality rate, but the majority of patients came to them seriously injured or ill. Also, this was before implementation of modern nursing care: the Bellevue Training School for Nurses in New York City, North America’s first nursing school based on the principles of Florence Nightingale, opened in 1873.

In their first year of operation, the Sisters realized that the combination of being located several miles away from the downtown core of Seattle and the unsavory name ‘Poor Farm’ was severely constraining their success as a hospital. So in July 1878 they moved to a new location at the corner of 5th and Madison Streets in the central core of Seattle, and they renamed their ten-patient facility Providence Hospital. The Sisters designated a night nurse to serve as a visiting/home health nurse and they accepted private-pay patients along with the indigent, whose care was paid for by King County taxpayers. The Sisters of Providence agreed to provide patients with liquor and medicine, both mainly in the form of whisky, a fact that likely helped them attract more patients.2

The Sisters’ list of patients included mainly loggers, miners, and sailors in the first few years, later mixing with hotelkeepers, fishermen, bar tenders, police officers, carpenters, and servants as the town grew in size. Many of their early patients were from Norway, Sweden, and Ireland, echoing the waves of immigrants entering the United States. Diagnoses recorded for patients included numerous injuries and infectious diseases—including cholera, typhoid, and smallpox—along with ‘whisky’ as a diagnosis, which later changed to ‘alcoholism.’ Their patient numbers grew, from just thirty hospital patients their first year, to close to two hundred patients by their fifth year of operation. The Sisters expanded their hospital to meet the increasing patient population.

Growing religious friction between the Catholic Sisters of Providence and the county’s mainly Protestant power elite, contributed to the King County Commissioners assuming responsibility for re-opening and running the King County Hospital in 1887. The King County patients were transferred from Providence Hospital back to the old Georgetown Poor Farm facility. Then, in 1906, the King County Hospital was expanded to a 225-bed facility at the Poor Farm site. It remained there until 1931 when the new 400-bed Harborview Hospital on Profanity Hill was opened. The old Georgetown facility, renamed King County Hospital Unit 2, was used as a convalescent and tuberculosis center until it was closed and demolished in 1956.5 The area where the King County Poor Farm was located is now a small park surrounded by an Interstate, industrial areas, and Boeing Field.

Harborview Hospital, now named Harborview Medical Center, still stands at the top of Profanity Hill, although the area is now officially called First Hill and nicknamed Pill Hill for the large number of medical centers now competing for both real estate and health care market share. Harborview Medical Center is owned by King County, and since 1967 the University of Washington has been contracted to provide the management and operations. Harborview Hospital has served as the main site for the region’s medical and nursing education. Since 1931 it has been the main tertiary-care training facility for the University of Washington’s School of Nursing.

Harborview Medical Center continues to fulfill its mission of providing quality health care to indigent, homeless, mentally ill, incarcerated, and non-English-speaking populations in King County. It is the largest hospital provider of charity care in Washington State. It also serves as the only Level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for Washington State, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho, a landmass close to 250,000 square kilometers with a total population of ten million people. Harborview Medical Center has nationally recognized programs, among these the pioneering Medic One pre-hospital emergency response system, the Sexual Assault Center, and Burn Center. Harborview also provides free professional medical interpreter services in over eighty languages, and has the innovative Community House Calls Program, a nurse-run program providing cultural mediation and advocacy for the area’s growing refugee and immigrant populations.

Harborview remains a shining beacon on Profanity Hill, rising above the skyscrapers of downtown Seattle. At night, it is literally the shining beacon on the hill, with blinking red lights directing rescue helicopters to its emergency heliport built on top of an underground parking garage on the edge of the hill. Sharing space with Harborview’s helipad is the narrow strip of green grass of Harbor View Park, with commanding views of Mount Rainier to the south, and of downtown Seattle and Puget Sound to the west. In the wooded area below Harbor View Park, extending down to Yesler Way, along the old Skid Road, are blue tarps and tents of the hundreds of homeless people living in the shadows of the hospital. Construction is underway to add a new public park, mixed-income public housing, and a new—and hopefully less slippery—pedestrian walkway connecting downtown Seattle to the Hospital on Profanity Hill.

References

- Seattle’s First Hill: King County Courthouse and Harborview Hospital. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_Id=7038. Priscilla Long, curator. Published March 22, 2001. Accessed November 5, 2013.

- Morgan M. Skid Road: An Informal Portrait of Seattle. New York, NY: Viking Press; 1951.

- Reinartz KF. History of King County Government 1853-2002. http:your.kingcounty.gov/kc150/service.htm. Published July 31, 2002. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Lucia E. Seattle’s Sisters of Providence: The Story of Providence Medical Center—Seattle’s First Hospital. http://providencearchives.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15352coll7/id/1651. Published 1978. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- Sheridan M. Seattle Landmark Nomination Application—Harborview Hospital, Center Wing. http://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/preservation/lpbcurrentnom_harborviewmedicalcenternomtext.pdf. Published May 4, 2009. Accessed November 21, 2014.

JOSEPHINE ENSIGN, RN, MPH, DrPH, teaches health policy and narrative medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Her literary non-fiction essays have appeared in many literary and health humanities journals. She writes a blog, Medical Margins, on health policy and nursing. Currently, she is researching and writing a book-length manuscript on the history and politics of Seattle’s health care safety net.

Leave a Reply