Annabelle Slingerland

Leiden, the Netherlands

|

| Craiglockhart War Hospital |

You are in World War I, back in its notorious trenches, hearing uninterrupted shooting, deafened from the shells, smelling cordite and dead bodies, fellow soldiers fall back on you, wounded or dead, grey with mud. War neurosis, nervous breakdown, neurasthenia or “shellshock” follows you like your own shadow. How on earth can you cope with all this?

Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburg, Scotland, pioneered the ground-breaking treatment of a condition initially hardly believed.1 The contrast of the hospital’s peace with the horrors of the war could not have been more pronounced, as two famous war poets and their psychiatrists brought it further to fame. Not unsurprisingly, the hospital starred in Pat Barker’s Booker Prize-winning historic novel The Regeneration Trilogy of 1995,2 its film by Gillies MacKinnon in 1997,3 and Stephen MacDonald’s award winning play Not About Heroes of 1982.4

From earliest times the grounds of the hospital were wild and barren, surrounded by Scottish hills. Strong winds blew through its bushes and forests, whispering through its leaves and glens from medieval times to its medical destiny in 1773. At that time, the Monro family, who were professors of anatomy, built the first houses on the site for themselves.1These were sold to the Hydropathic Company in 1876, but demolished in favor of completing a new giant villa in the Italian style in 1880. Here patients were treated with what we now call hydrotherapy, a cure using water, which was enormously popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when spas arose everywhere, the most famous being Malvern in western England, clients including Florence Nightingale, Dickens, Darwin, Tennyson, Carlyle and Wilberforce.5-7

After the Battle of the Somme in 1916, the new word “shellshock” was whispered in medical circles and coined by a medical officer, Charles Meyers, as it swept through the grey battlefields and trenches of World War I. It accounted for 80,000 to 325,000 discharges from active service, including high ranks,1,8 so that the armed forces were compelled to immediately establish specialized hospitals.

Craiglockhart was one of the first hospitals dedicated to shellshock. As a military psychiatric institution, it would treat 1736 officers and 65 German prisoners of war, at a rate of between 50 and 100 admissions per month.1,8 At first the hospital’s objectives were confused, as the doctors dealt with an unknown medical condition. Diagnoses varied greatly: neurasthenia, migraine, gas poisoning, piles, inability to sleep or eat, mutism, hysterical paralyses and functional disability (noted down for non-officers as hysteria). Treatment was by trial and error. The eminent psychiatrist W.H.R. Rivers favored “talking therapy,” believing that the condition had a psychological origin, as he wrote “The Repression of War Experience” in the Lancet.9 Arthur Brock kept his patients as active as possible. Hobbies were encouraged, including writing for the hospital magazine The Hydra, and his treatments contrasted favorably with the paralyzed nerves hypothesis whose primary treatment was electroshock therapy.

The military was often suspicious of whether or not a given condition was a way to avoid service at the front: “the local Director of Medical Services nourished a deep-rooted prejudice against [Craiglockhart], never had and never would recognize the existence of such a thing as shellshock.”1,8 The hospital was visited twice for inspection and on both occasions had the commanding officer replaced. The destiny of patients presented for the board remained clear, no other conclusions being entertained in the eyes of the military authorities than “ready to active service,” medically unfit (DMU), home service (HS), or transfer to other hospitals.1,8 Among the latter three, soldiers themselves often regarded admission as well as discharge an act of failure and a blow to their reputations.

|

|

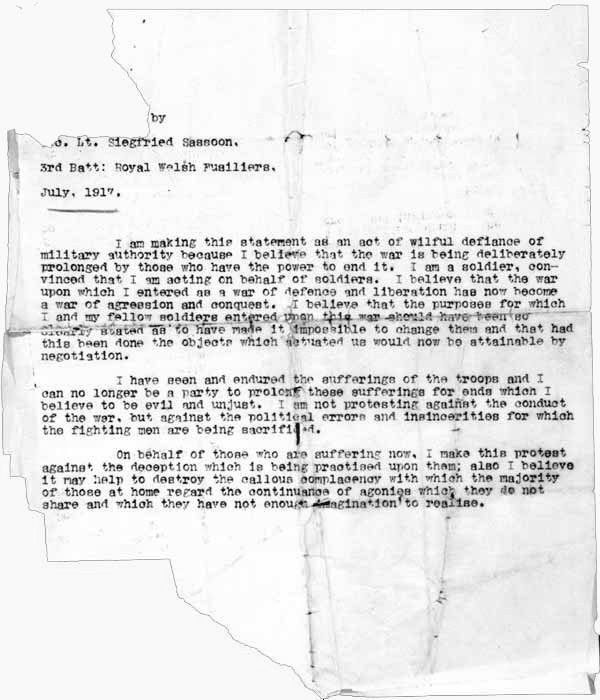

“Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration”(1917) |

Poet Siegried L. Sassoon became an inmate in 1917 after having received the Military Cross in July 1916 for conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy’s trenches. He had remained under fire for one and a half hours, collecting and bringing in the wounded.11 Half a year later his best friend was killed (his brother had already been killed at Gallipoli), and grief made him refuse to serve further in the army. He wrote his commanding officer “Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration,” expressing his disgust as “an act of wilful defiance of military authority” and that he had “entered as a war of defence and liberation,” but that it had now turned into one of “aggression and conquest”12

Forwarded to the press, his anti-war letter was read out by a member of parliament and published in the London Times the next day. This could not be left unresponded. His friend Robert Graves organised a narrow escape, preventing court martial by suggesting that Sassoon was suffering from shellshock. He therefore instead was eligible for Craiglockhart.1,8

His stay enriched his poetry and he wrote “Survivors”; he was also allowed time and discussion, mentoring fellow-poets like Wilfred Owen.10 Sassoon himself was treated by psychiatrist W.H.R. Rivers, who emphasized that soldiers in the field would benefit more from “a cup of tea” than from Sassoon’s protest. He believed that “a soldier who suffered a neurosis had not lost his reason, but was laboring under the weight of too much reason.”8 Sassoon finally “cured himself” without withdrawing his letter, but by using his still distinguished valor to help end war through his return to the battlefield in France. Ironically, he was shot by a British fellow who had taken him for a German, sent home, and thus survived, in contrast to his poet-fellow.

Poet Wilfred Owen had been admitted to Craiglockhart in the same year as Sassoon, being severely traumatised by the dead body of a fellow officer. His psychiatrist Dr Arthur Brock encouraged him to write, completing the poems “Dulce et Decorum Est” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth” and editing The Hydra. Owen commented “Many of us who came to the hydro slightly ill are now getting dangerously well.” Against medical advice, Sassoon suggested to Owen that returning to the Front would improve his poetry. It did indeed, leaving his legacy just before he died at the Front, one week before the Armistice, 4 november 1918.10

In his last poem “Parable of the Old Man and the Young,” Owen had Abraham of the Testament “build parapets and trenches,” and “stretch forth the knife to slay his son.” The old rhyme scheme becomes ominous as it nears its crescendo. In the Bible, Abraham stays his hand at the voice of an angel and kills a ram instead. For Owen, the Great War was a more treacherous inferno where the consoling voice of the angel telling to stop is ignored, and soldiers kept killing and being killed. For him, “Abram” thus “slews his son” and herewith “half the seed of Europe, one by one.”13

After World War I Craiglockhart was turned into a convent for the Society of the Sacred Heart and later a Catholic teacher training college. Currently it is part of Edinburg (Napier) University. W.H.R. Rivers died suddenly in 1922, touching Sassoon deeply. Sassoon himself brought Owen’s poetry to the public’s attention, continued writing novels and poetry, receiving the high honours in England in 1951 from the very authorities he criticized earlier, and died in 1967.10 Most shellshock hospitals closed shortly after the Great War.1,8 Nowadays, shellshock’s equivalents, War Fatigue or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), are better researched and treated, though there still remains much to learn.

References

- BBC Did Craiglockhart. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/z9g7fg8#orb-banner, 21 January 2015)

- Pat Barker, The Regeneration Trilogy, (New York, USA: Viking Books, 1996).

- Gillies MacKinnon, Regeneration, (UK: Allan Scoot and Peter R. Simpson, 1997/US Behind the Lines 1998).

- Stephan MacDonald, Not about heroes, 1982.

- James Bradley, Mageurite Dupree and Alastair Durie, Taking the Water Cure: The Hydropathic Movement in Scotland, 1840-1940, (Business and Economic History 26 (2): 429).

- William H.R.Rivers, Medicine at the Congress. (British Medical Journal 2 (1089): 784–785. 12 November 1881).

- Sebastian Kneipp, My Water Cure, As Tested Through More than Thirty Years, and Described for the Healing of Diseases and the Preservation of Health, (Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1891).

- Professor Joanna Bourke, Shell Shock during World War One, (http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwone/shellshock_01.shtml, 23 January 2015).

- William H.R. Rivers, The Repression of War Experience, (Lancet December 4 1917; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2066211/ 24 January 2015).

- The War Poets at Craiglockhart, (http://sites.scran.ac.uk/Warp/index.htm 22 January 2015).

- Announcement Military Cross Sassoon, (Supplement to The London Gazette, 27 july 2016 https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/29684/supplement/7441 21 January 2015).Siegfried L. Sassoon. Finished with the War: A Soldier’s Declaration. 1917. (http://siegfriedsassoon.firstworldwarrelics.co.uk/html/protest.html 20 January 2015).

- Wilfred Owen. Poem of the Week, (The Guardian 8 june 2009; http://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2009/jun/08/poem-of-the-week-wilfred-owen and http://www.wilfredowen.org.uk/poetry/the-parable-of-the-old-man-and-the-young 19 January 2015).

ANNABELLE S. SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR was intrigued by WWI’s Battles of Verdun (France) and Gallipoli at Canakkale’s Dardanelles (Turkey). Her interest further deveoped while swimming the Hellespont, by Veterans Centres in the United States, and during the 9th Congress of the International Brain Injury Association in Edinburgh. May the story of Craiglockhart Hospital, inspired by the Rolls family, touch more than a nerve in 2015.

Spring 2015 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply