Melanie Cheng

Melbourne, Australia

It was her mother’s doing. After all, it was her mother who taught her how to read. Not just in the literal sense—with Little Golden Books a good year before she started school—but in the broader sense of the word, through the sharing of musty, broken-backed treasures. Entire summer holidays could be lost in the alleyways of Dickens’ nineteenth century Paris or on the lush plantations of Scarlett O’Hara’s Atlanta.

The seed had been sowed. Through a tumultuous puberty it flowered. Thanks to her mother, who fed it delicacies like To Kill a Mockingbird and Lord of the Flies. Before long, like all living things given the right conditions, it grew out of control.

What she lacked in skill, she made up for with ambition, starting an unauthorized sequel to Gone With The Wind a few days shy of her sixteenth birthday. She filled notebook after notebook with book reviews (less critiques than homages to her most beloved authors) and carried a pad of paper in her jeans pocket to capture every idea, no matter how absurd, that flitted through her busy mind. But then one day, around the middle of Year 11, she turned her attention to more serious things. Like math. And chemistry. Because, in spite of her mother’s love affair with literature, her parents were practical people, for whom writing, while a perfectly respectable—even esteemed—hobby, was not a viable profession.

She chose medicine because she was good at most subjects but brilliant at none. And because she took pleasure in helping others and getting to the bottom of a problem. Which were not bad reasons, in and of themselves—some might say they were rather fine motivations for becoming a doctor. Except that they didn’t take into account her emotional fragility. After years of inhabiting the lives of fictional characters she had become skilled at feeling others’ pain, which was not a particularly useful trait—some might even call it a disability—in the pain factory that was the tertiary teaching hospital.

Her internship was excruciating, her residency crippling. She almost gave up, except that her unwillingness to admit defeat prevailed over her brittle sensitivity. General practice did not cross her mind until a chance encounter with an old acquaintance. I always thought that’s what you were going to be. A country practice, that sort of thing. The acquaintance had meant it as an insult—general practice was an easy training program to get into—but she chose to ignore the condescension behind the words.

Of course. General practice. Her own office. Patients who dressed themselves in the morning, who wore clothes, who for the most part could walk and talk and think. It was something of a revelation. Clouds cleared. Yes. She would be a GP.

There was just as much responsibility—perhaps more—being a GP as there was working as a resident in the hospital. There were no grey-haired consultants to cower behind. Decisions were hers and hers alone. It was empowering but also isolating. At least on the ward there were other, similarly disillusioned, doctors to share an inappropriate joke with. In general practice she could go a whole day without seeing anyone except the patients who stumbled through her door. But she enjoyed it. Mainly because general practice provided something the hospitals hadn’t. Stories. Tragedies. Comedies. Even the occasional psychological thriller. Stories heavy with meaning and stories, which, seemingly, had no meaning at all.

For a while, that was enough. She read books again. She travelled. She met a man, got married. But then one day it returned, like an itch in a place she couldn’t reach. She very nearly went to see a GP herself. Got as far as the waiting room before realizing she did not have the words to describe it. Restlessness. Anxiety. Some kind of visceral agitation. Perhaps the most accurate term was one taken from the medical vocabulary itself: akathisia, a word with Greek origins, meaning inability to sit.

It was really only once an old friend, a writer, told her about a literary prize for doctors, that she finally realized what her body wanted her to do. As she sat down with her laptop she felt an immediate calming of the nerves. It was frustrating—the words on the page never quite matched the fluency and clarity of the prose in her mind—but it was the most content she had felt in years.

To say that the writing alone was enough would have been a lie. She checked her inbox daily—sometimes two or three times a day—for a subject heading with the word prize, or winner, or congratulations. Needless to say, it never came, but the journal did offer to publish her story. She ordered copies for friends and family but never expected people to read it. Not strangers. Not people who did not know her or did not recognize her name. She imagined most subscribers, busy doctors like her, would flick through the issue and, on finding nothing groundbreaking, return to other, more pleasing ways of spending their time. So the email came as a shock. A lovely—perhaps the loveliest—surprise.

Dear Doctor,

I’m an 85 year-old GP, loved the work, especially delivering babies—each one is a miracle—and have been retired for 14 years. I read medical journals to keep in touch with medical thinking.

So I came across your writing, intending to skim through it. But I was riveted from the very first sentence. Your writing is outstanding, highly skilled and strictly true, written with a wonderful elegance and with a lovely understanding.

I can’t really find the words to express how wonderful is your writing, but thank you. I will read everything you publish.

With total admiration,

Dr. M—

The little she knew about this man commanded her respect: his age, his dedication to general practice, his eloquent turn of phrase. His praise made her feel honoured and humbled, unworthy even. It took her a day to compose her reply. Another day to send it. She wanted her words to convey many things: her gratitude, her commitment to writing, but most importantly, a justification of his admiration.

Dear Dr. M—

I’m so pleased you enjoyed my story.

Like you, I am a GP, and also like you, I love my work (most of the time). Writing helps me make sense of the stories—the illnesses, the tragedies, the celebrations, the relationships. But I’m just a fledgling (writer and GP) and I’m sure you have many more stories than me.

Please know that your kind words have encouraged me to keep writing.

Warmest regards,

M—

Years passed. She had one baby, and then another. She kept writing. She entered competitions. Every so often she got shortlisted. One day, after a flurry of rejection letters, a prestigious literary journal picked up one of her pieces. When the dust had settled she remember Dr M—‘s vow to read everything she published. She sat down at her laptop again to write another email. She did not want to boast. Only to say thank you.

For weeks she heard nothing. And then it occurred to her that two years was a long time. Especially when you were eighty-five.

His obituary was second on the list of her Google search results. A concise entry on the Tributes page of the Sydney Morning Herald. Long time GP. Beloved husband. Loving father. Fondly remembered by his grandchildren. Aged 86 years.

She felt profoundly sad. Her success was too slow. Her correspondence too tardy. Weeks turned into months. She soon lost hope that anyone was checking his email. There would be no neat closure. No unlikely friendship. No warm-and-fuzzy Hollywoodesque ending.

She was sad for a while.

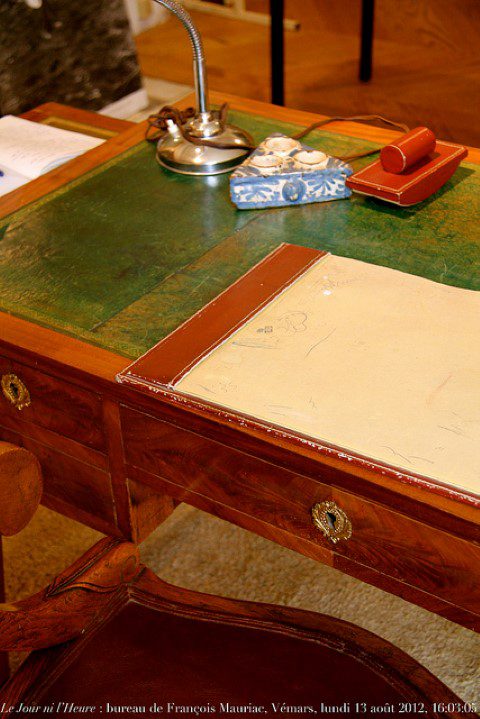

And then one day, when the autumn sun filtered through the cellophane leaves of the Japanese maple tree in the front yard, she felt something like an itch, sat down at her desk and started typing.

Leave a Reply