James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

The first half of this article was previously published in Hektoen International, Summer 2010 as The castrati: a physician’s perspective, part I

Medical aspects

In this second part, we turn to the medical aspects of our subject and questions of by whom and by what methods were these operations performed. One often reads that they were done by “barber surgeons,” but in fact these procedures were performed by surgeons who were favored by the aristocracy and represented the highest echelons of the medical profession. Evidence for this and the toleration afforded the practice by officialdom can be found in an article by Ralph R Landes, “Tommaso Alghisi: Florentine Lithotomist (1669-1713).”1 The paper lists the surgeons at the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova in the year 1700. Included along with their yearly stipend we read, “Antonio Santarelli, Master dei Castrati, 14 scudi and Girolamo Coramboni, Second Master dei Castrati, 18 scudi.” A commentary on the history of the hospital written in 1853 notes: “Eight beds were earmarked [at the Maria Nuova Hospital] to receive the unhappy children, who through the most inhuman barbarity of their own parents were for the filthy love of money condemned to emasculation.”

|

| Charles Burney |

Charles Burney, English musician, composer, music historian and author of The present State of Music in France and Italy, or the Journal of a Tour through these Countries undertaken to Collect Material for a General History of Music, 1771 and 1772, has much to say on the subject of castrati. He records his efforts to learn where the operations were performed:

I inquired throughout Italy at what place boys qualified for singing by castration, but could get no certain intelligence. I was told at Milan that it was Venice; at Venice, that it was at Bologna; but at Bologna the fact was denied and I was sent to Naples. The operation most certainly is against the law in all these places, as well as against nature; and all the Italians are so much ashamed of it, that in every province they transfer it to some other.

Although the procedure was done clandestinely, Bologna, Lecce and Norcia became centers for the operation, which was performed by surgeons who as a result of their skill and prestige were called to capitals throughout Europe. At the time of Dr. Burney’s travels in Italy, the practice of castration was illegal and also punishable by excommunication. Parents, probably out of shame, sought to conceal the reasons for the operation by medicalizing its necessity with fabrications that included injury (such as a fall from a horse), disease (tuberculosis or hernia) or attacks by animals (favorites were swans or wild pigs).

We know little about the operation itself, though it may have been relatively mild and safe. The testicles may have been removed or caused to wither through pressure, maceration, or the cutting of the spermatic cords. The single and most often quoted description of the surgery comes from a work published in French in 1707 and later translated into English in 1717 under the pseudonym of Charles d’Ancillon, an author who describes himself a man of character, titled, Eunuchism Displayed.

The boy was placed in a warm bath to make him more tractable. Some small time after they pressed the Jugular Veins which made the Party so stupid and insensible that he fell into a kind of Apoplexy and then the action was performed with scarce any Pain at all to the patient. Sometimes they used to give a certain quantity of opium to persons designed for Castration whom they cut while they were in their dead Sleep and took from them those Parts which Nature took so great a care to form; but it was observed that most who had been cut after this manner died by this Narcotick.2

The use of opium and bilateral jugular compression would no doubt have been hazardous. A BBC documentary produced by Nicholas Clapton on the castrati illustrated one method of castration that employed cuplike tongs, which were heated to incandescence to achieve cauterization and thereby remove the entire scrotum.3 Such a procedure would surely have incurred both morbidity and mortality.

Both Franz Joseph Haydn and Gioachino Rossini were talented singers as children and left us firsthand recollections of their narrow escape from being made castrati.

H.C. Robbins Landon describes the events surrounding Haydn’s near escape in the 1740s:

At the time many castrati were employed at the Court and the Viennese churches, and the director of the choir School no doubt considered that he was about to make young Haydn’s fortune when he brought forth a plan to make him a permanent soprano, and actually asked his father for permission. The father totally disapproved of this proposal, set forth at once for Vienna and thinking that the operation might have already been performed entered the room where his son was and asked, ‘Sepperl, does anything hurt you? Can you still walk?’ Delighted to find his son unharmed, he protested against any further proposals of this kind, and a castrato who happened to be there even strengthened him in his resolve.4

Rossini recalling similar events writes:

I came within a hair’s breath of belonging to that famous corporation—or rather let us say de-corporation. As a child, I had a lovely voice and my parents used it to have me earn a few paoli by singing in churches. One uncle of mine, a barber by trade, had convinced my father of the opportunity that he had seen, the breaking of my voice should not be allowed to compromise an organ which—poor as we were, and as I had shown some predisposition towards music—could have become an assured future source of income for us all. Most of the castrati in fact, and in particular those dedicated to a theatrical career, lived in opulence.5

The physiological consequences of castration

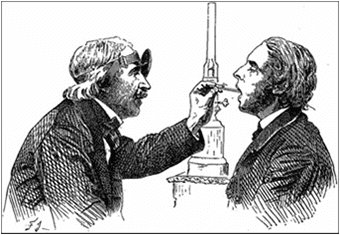

Germaine to our subject is an understanding of the history of the human voice. The ancients recognized the trachea and larynx as the source of voice production, and Aristotle is credited with being the first author to mention the larynx. It would be left to the great anatomists, Leonardo Da Vinci in 1519, Vesalius in 1555, and Giovanni Morgagni in 1719, to describe in detail the anatomy of the organ and recognize its relationship to speech. The term cordes vocales (vocal cords) was coined by Antonin Ferrin, a French anatomist, who in 1741 described them as comparable to the strings of a violin and activated by a stream of air. While the term “vocal cords” persists in common parlance, these structures are in reality vocal folds. It was not until 1854 that Manuel Garcia, a Spanish-born voice teacher, first visualized these vibrating structures in a living human being.6 Garcia had been preoccupied with the possibility of observing the movements of the vocal cords when, while walking on a street in Paris, he suddenly noticed the flashing of the sun on the window panes of a house and hit upon the idea of one mirror reflecting on another. He purchased a small dental mirror for six francs and, with this mirror placed in his throat, using reflected sunlight and a hand held mirror, he was able for the first time to see his larynx and vocal folds. Thus the clinical art of indirect laryngoscopy was born, aided by the fact that Garcia himself seems to have had little or no gag reflex.

|

| Manuel Garcia Traité complet de l’Art du Chant, 8 ed. Paris: Heugel et Cie; 1884 |

At birth the vocal folds consist of two parts, a firm cartilaginous portion and a thin pliable membranous portion, which is crucial in speaking and singing. The pitch of the voice is determined by the frequency of vibration of the vocal folds and inversely related to their length. From birth until the onset of puberty the male and female vocal folds remain at the same size. With the onset of puberty, boys experience a progressive decrease in the fundamental pitch of the voice, which is accompanied by a progressive increase in the length of the vocal folds. Under the influence of testosterone, the male vocal folds grow from a mean total length of 17.3 mm in prepuberty to 28.9 mm in adulthood, an increase of 67%. In contrast, female vocal folds grow from 17.3 to 21.4 mm, an increase of 24%.7 The castrato’s vocal folds would remain at their prepubescent length thus explaining their ability to sing in a pitch range similar to that of an adult soprano. It has been observed that testosterone produces swelling and vascular congestion of the vocal folds accompanied by the accumulation of collagenous and elastic tissue, resulting in a thickening of the folds. The lack of these changes in adult female vocal folds and presumably those of the castrati accounts for the greater flexibility of their voices. This allowed the castrati to execute florid coloratura, a hallmark of bel canto singing, the elaborate ornamentation and embellishment for which the castrati were so famous. With the onset of puberty the thyroid cartilage increases to an anteroposterior length that is three times greater in men than in women, giving rise to the male ‘Adam’s apple,’ which was absent in the castrati. Only one post-mortem examination of a castrato has been recorded in the literature. It was published in 1909 and describes a 28-year-old castrato from Umbria, Italy. The paper documents the small dimensions of the larynx and vocal cords consistent with those of a female high soprano. Because somatic growth was not inhibited by the surgery, as the castrato matured, his voice developed the resonating chambers—sinuses, pharynx, oral cavity and thorax—of an adult. These changes combined with intensive vocal training created a voice of unique timbre.

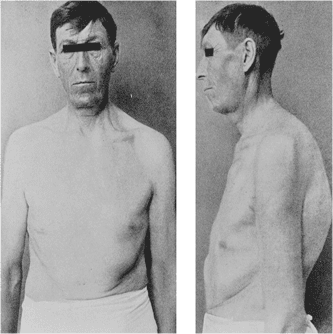

The biological and psychological impact of the operation, as correctly noted by Enid and Richard Peschel, has been underestimated even into the 20th century.8 In support of this claim they cite the following passage from Angus Heriot’s The Castrati in Opera published in 1974: “castration appears, for all its cruelty, to have had surprisingly little effect on the general health and well-being of the subject, any more than on his sexual impulses and intellectual capacities. The hurt was very largely a psychological one in an age when virility was accounted a sovereign virtue.”9 Viewed from a 21st century perspective, an endocrinologist recognizes that these men suffered from primary hypogonadism and the physiological changes that accompany this syndrome. Descriptions of the castrati from the 18th century mention the salient clinical features associated with hypogonadism. Tallness of stature, unusual at the time, and an increase in size of the chest were features frequently mentioned and satirized in drawings.10 Both these phenomena resulted from the delayed closure of the epiphyseal growth centers located at the ends of the long bones of the extremities and ribs. The growth centers are cartilaginous plates that normally ossify as they close resulting in the cessation of growth. Testosterone in tissue surrounding the growth plates is converted by the enzyme aromatase to estrogenic steroids that actually bring about the closure of the epiphyseal plate.

In the castrati, the absence of testosterone available for conversion to estrogenic steroids allowed for continued formation of bone at the epiphyseal plate and lengthening of the ribs and the extremities. Normal male secondary sex characteristics failed to appear and there was an absence of hair on the extremities, a lack of facial hair growth, and an absence of a receding hair line and baldness. Their skin was smooth and pale; the pallor might have resulted from a lower hemoglobin level than would have been present in a normal male, secondary to decreased levels of testosterone. There was a tendency toward obesity, rounding of the hips and narrowness of the shoulders, curvature of the spine and gynecomastia. The curvature of the spine was indicative of osteoporosis. As a group, the castrati, because they were deficient in testosterone, would have been at increased risk for this condition. Gynecomastia, or abnormal breast development in a male, occurs in the syndrome of hypogonadism as a result of a relative deficiency of androgen secretion and resulting increases in pituitary hormones, lutenizing hormone (LH), and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). The excess of these pituitary hormones in a castrated male, or an individual with hypogonadism, leads to an excess in estradiol and an alteration of the estrodiol/testosterone ratio, resulting in gynecomastia. This abnormal breast development and lack of male secondary sex characteristics contributed to instances of sexual ambivalence that were mentioned when young castrati took female roles on the opera stage.

|

| 54 year old Skoptzy man who had been castrated at the age of 15 |

It may come as a surprise to learn that it was still possible to study the medical consequences of castration as late as the 20th century. This information comes from studies conducted on a religious sect that practiced castration in Russia, the Skoptzy (Russian for castrated). It was estimated that 1000 to 2000 Skoptzy were present in Soviet Russia in 1930—500 of who were living in Moscow—but as a result of severe persecution, by 1962, none were thought to be alive. Prior to World War II, three medical studies were published with photographs and anthropologic measurements on Skoptzy men many who had been castrated in childhood many years earlier. Similar studies have been performed on eunuchs who were part of the Imperial Court in China’s Forbidden City and eunuchs of the Ottoman court. These studies documented increased height, osteoporosis, instances of pituitary enlargement, atrophy of the prostate and gynecomastia— findings noted in the descriptions of the castrati. No mention in these studies is made of laryngeal anatomy or their having had a role as singers.11

The biographies of famous castrati from the “Golden Age” of Opera (1700 -1760) include frequent references to their heterosexual exploits. Endocrinologists agree that castration before the onset of puberty would result in permanent sterility and impotence. Urologists also agree on this point as documented in a survey conducted by Meyer M. Melicow.12 The variable age and uncertain techniques employed at the time of castration would certainly have led to variability in the suppression of their secondary sex characteristics and must be considered in evaluating 18th century accounts of their sexual exploits. Illustrative of this point is an anecdote about Pope Innocent XI (1676-1689). He was one of the least understanding popes and known as Minga, a Milanese dialect word meaning “no.” Since castrati were not capable of reproduction, the Church would not sanctify their entry into matrimony. A castrato by the name of Cortona petitioned to be allowed to marry since his castration had been badly carried out and he was fit for marriage. Pope Innocent XI read the letter and wrote in the margin, “let him be castrated better.”

There have been suggestions that the castrati may have enjoyed an increased life expectancy. This would be of scientific interest as it relates to the observation that women live longer than men, which has lead to the hypothesis that testosterone, by some mechanism, might contribute to a shorter life span. In 1993, Eberhard and Susan Neishlag published in the journal, Nature, the results of a survey on the longevity of 50 castrati with birth dates between the year 1581 and 1858, who are mentioned in published encyclopedias and biographies.13 Their control group was a series of 200 intact male singers from similar sources born during the same period. The two groups were indistinguishable; the castrati had a lifespan of 65.5 + 18.8 years and the intact singers 64.3 + 14.1 years (mean + SD). It would be of interest to know the life span of the normal male population at that time. Did professional singers as a sheltered population enjoy a longer life-expectancy, as noted in accounts describing the cosseted treatment of young castrati in the conservatories of Naples? The previously mentioned studies on the Skoptzy and Oriental eunuchs revealed no increase in longevity. An article published in 1969 on the survival of institutionalized mentally retarded patients in Kansas, all of whom had been castrated for eugenic purposes, found a slight but not statistically significant increase in the longevity of castrated men when compared with intact men matched for their date of birth.14 The mean age of castration was twenty, and no mention was made if any of these individuals were castrated before puberty.

Psychological impact

|

| Stefano Dionisi as Farinelli in the film Farinelli – Il Castrato (1994) |

We have said little of the psychological impact that this operation would have had on young boys in a society that highly prized virility. The 1994 film Farinelli, based on the life of the one of the most famous castrati, Carlo Broschi, begins with a scene depicting the suicide of a young castrato at a conservatory in Naples who leaps to his death from a balcony. If suicides occurred, such incidents do not seem to have been documented. Undoubtedly young castrati endured ridicule from their peers. Castrati who did not make the cut as operatic stars might still have found a place singing in church choirs; one shudders to consider the fate of a boy whose voice and singing abilities failed to develop.

Mozart comments in a letter to his sister, Nannerl, on the arrogance he found typical of castrati.15 Such behavior might have been the byproduct of stardom or perhaps a compensatory mechanism for a lack of self-esteem. Indeed Farinelli referred to himself as being “despicable,” and the 19th century castrato, Velluti, referred to the “utensils” missing from his “knapsack.” A celebrated castrato Filippo Baltari (1682-1766) left a verse autobiography, Frutti del mondo (Fruits of the World), wherein he contrasts the material rewards his singing garnered with the sorrow he experienced as a result of his neutered sexuality. Baltari refers to himself derogatorily as a capon and explains that, because he was an evirato, he had to give up loving and longing for women.16

The voice of the castrato

We are now in a position to understand how the physiologic changes associated with hypogonadism created the timbre of the castrato voice. The prepubescent length of the vocal folds in the castrato account for his ability to sing in a pitch range starting at E below middle C on a piano to C or D two octaves above middle C (E3 to D6).17 The voice of the castrato possessed the resonance of an adult and was the product of the enlarged thoracic cavity as well as the vocal track above the vocal folds, including the oral cavity and nasal sinuses. The increased thoracic cavity contributed to the castrato’s ability to sustain individual notes or sing many notes without taking a breath. The extensive vocal training that they received allowed the castrati to cultivate a vocal technique, known as messa di voce, to a degree that became legendary. Messa di voce was the ability to start very softly on a given pitch and develop a gradual crescendo and subsequent diminuendo without varying the pitch. Testifying to the flexibility of their vocal folds, an aria sung by the famous castrato Farinelli included an extended passage lasting almost a minute with notes sung at the astounding rate of 1000 notes / minute. Castrati did not resort to the use of the falsetto, the technique employed by modern countertenors. This technique, referred to as second-mode phonation, employs closure of the arytenoids cartilages and thinning of the vocal folds so as to allow them to vibrate at a higher frequency. Paradoxically this vocal technique was labeled “false” while voice of the castrato was deemed “naturale.”18

|

| Alessandro Moreschi, c. 1880 |

Considerable interest is being directed toward understanding the voice of the castrato, the voce bianca or voce naturale as it was called in the 18th century. The subject has been approached from several directions. There are the first-hand descriptions of their singing and performance by musical connoisseurs. These accounts refer to the “heavenly or otherworldly sound” that they heard, as well as the profound effect the voice of the castrati had on their listeners. They also convey the impressive vocal techniques the castrati employed. This point can also be appreciated through the study of musical scores written specifically for castrati. Gramophone recordings made early in the 20th century of Alessandro Moreschi, the last surviving castrato of the Sistine Chapel choir, have been studied to understand the acoustical characteristics of his voice.19 The information gained from this unique opportunity is limited by the primitive state of the recording techniques in the years 1902 and 1904. These recordings have caught the attention of acoustical engineers who now strive to electronically recreate the voice of the castrato. The music for the sound track in the 1994 film Farinelli combined the voice of a countertenor with that of a soprano to create a single voice.20 Acoustical engineer David M. Howard, in the recent BBC documentary Castrato, describes a similar project that attempts to recreate the voice of a castrato by fusing solely male voices singing Handel’s famous aria Ombra mai fu from the opera Xerxes. He recorded separately in an acoustically anechoic room the singing of this aria by an unaccompanied York Minster boy chorister and a high tenor. Through electronic manipulation referred to as “morphing” he produced a single “voice” that was then played and accompanied by a live chamber ensemble to produce a complete musical number (the reverse of a “music-minus-one” recording).

Our understanding of the castrato voice is further enhanced by rare instances of “natural” castrati; individuals born with the syndrome of hypogonadism who have become professional vocalists. Finally, there are studies of the opera culture in the 18th century that attempt to understand what has been called, the “period ear.”21 Nicholas Clapton, the author of Moreschi and the Voice of the Castrato, commenting on the recordings of Alessandro Moreschi’s voice, notes that to our ears the repertory and style of singing in these recordings is foreign to modern tastes and, hence, not necessarily appealing. He points out that there is no way of knowing if we could hear the actual voice of the castrato as it sounded in the 17th and 18th century opera that we would necessarily like it.

Twilight of the castrati

The twilight of the castrati begins with the writings of French authors, including Voltaire and Rousseau. The latter observed: “In Italy there are barbarous fathers who sacrifice nature for financial gain and hand over their children for this operation.” Even in Italy, the arrogant and outlandish conduct of famous castrati came under attack. In 1720, the composer Benedetto Marcello penned one of the most racy satires, Il teatro alla moda (The Fashionable Theater), specifically targeting the castrati for his bards. John Rosselli points to the economic revival beginning in 1730 following a period of prolonged depression that reversed a trend toward “Christian asceticism and tipped the balance away from gambling a son’s virility on success as an opera singer or tenured position as a church singer.”

|

| Aureliano in Palmira stage setting from orginial production at La Scala |

Mozart included roles for castrati in his operas Idomeneo and La Clemenza di Tito; both examples of Opera seria. But Opera seria was being eclipsed by the public taste for Opera buffa with its emphasis on real people in ordinary situations; such opera was not suited to the voice of the castrato. This trend is reflected in Mozart’s three great Da Ponte operas and his singspiel Die Zauberflöte. Also important was the rise of the prima donna during the 17th and 18th centuries, a result of easing the prohibition and the stigmatization against women appearing on the stage. With the ascendancy of what Henry Pleasants labeled “A New Kind of Tenor,” there was little room left for the castrati.22 Gilbert-Louis Duprez (1806-1896) became the first “king of the high Cs.” He is said to have learned his art from Domenico Donazelli (1790 – 1873), who had discovered a technique of lowering the larynx to produce a darker and more powerful tenor voice that also allowed production of the “notorious top C.”

By the beginning of the 19th century the demand for castrati on the opera stage was in steep decline. Rossini’s only opera for a castrato, Aureliano in Palmira, was produced in 1813. Giacomo Meyerbeer is generally considered the last composer to write an operatic role for a castrato, that of Armando in Il Crociato in Egitto of 1824. Richard Wagner, who heard some of the last castrati and was very impressed with their singing, is credited with giving them a final passing glance. Wagner is said to have contemplated casting a castrato for the role of Klingsor, the evil sorcerer in his final opera, Parsifal, who prior to the action of the opera, had emasculated himself to control his sexual desires and thereby gain admission to the Knights of the Holy Grail (Klingsor, if castrated after puberty, however, would not have had the voice of a castrato).

Conclusion

There is still an active interest in the castrati. No account of 18th century opera history is complete if it fails to mention the castrati. Nor is the history of the voice complete without recognition of their contribution to the art and pedagogy of bel canto singing. Scholarly books and articles still continue to appear in print. January of this year saw the release of two CDs devoted to the art of the castrati. The first, titled Sacrificiium, by Italian soprano Cecilia Bartoli, features a collection of arias composed for famous castrati of the 18th century. The second release, Mozart: Arias for Male Soprano, is by Michael Maniaci, an American born countertenor, whose larynx failed to develop allowing him to sing in a soprano range without sounding like a countertenor.

The phenomenon of the castrati as described in this paper raises ethical issues that leave us shuddering. Today, “child abuse,” would seem to be the term we would affix to these practices. The daily newspapers tell us that child abuse is still prevalent and the promise of financial gain still leads parents to exploit their children: witness the spectacle of childhood beauty contests. Today it seems incomprehensible that children 8 to 10 years of age would be deemed capable of giving written consent for castration, while we still struggle to find the appropriate age a minor might sign a consent form for a legitimate medical intervention. Before we feel too smug, we should remind ourselves that castration and sterilization were authorized for eugenic purposes well into the 20th century and that the United States was the first country to legalize this practice—a fact that was cited by Nazi propaganda in defending Germany’s forced sterilization program in 1936 and that was raised yet again in their defense during the Nuremberg trials. Even today, instances of complicity by members of the medical profession in ethically questionable medical practices and surgical procedures are continuously uncovered.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the friends with whom I have discussed this paper and from whose input I have benefited:

David J. Buch, PhD, Visiting Professor in the Committee on Theater and Performance Studies at the University of Chicago;

Donald Zimmerman, MD, Chairman of Pediatric Endocrinology, Children’s Memorial Hospital, Professor of Pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg

School of Medicine;

Robert W. Carton, MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Rush University Medical Center;

Special thanks to Jonna Peterson, MLIS, Reference Librarian, Library of Rush University Medical Center.

Notes

- Ralph R. Landes, Tommaso Alghisi: Florentine Lithotomist (1669-1713), Journal of the history of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 325-349, 1952

- John S. Jenkins, The voice of the Castrato, Lancet, 351, 1877-80, 1998.

- BBC Documentary, Castrato, (59 minutes).

- H.C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: A Documentary Study, Rizzoli, New York, 1981, p. 36.

- Gaia Sevadio, Rossini, Carroll & Graf publishers, New York, 2003, p.15.

- Manuel Garcia, Observations on the Human Voice, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Volume 7, 399-410, 1854-1855.

- John S. Jenkins, The Lost Voice: A History of the Castrato, Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism, 13, 1503-1508, 2000.

- Enid Rhodes Peschel & Richard E. Peschel, Medical Insights into the Castrati, American Scientist, 75, 578-583, 1987.

- Angus Heriot, The Castrati in Opera, Da Capo Press, New York, 1974

- Illustrative of this point is a famous engraving by William Hogarth satirizing Handel’s opera Flavio (1723).

- Jean D. Wilson and Claus Roethrborn, Long-term consequences of Castration in Men: Lessons from the Skoptzy and Eunuchs of the Chinese and Ottoman Courts, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 84, 4324-4331, 1999.

- Meyer M. Melicow, Castrati Singers and the Lost “Cords,” Bull. N.Y. Acad. Med. 59(8), Oct. 1983, pp. 744-764.

- Eberhard Nieschlag, Susan Nieschlag, & Herman Behre, Life span and testosterone, Nature, 366, 215, 1993

- James B. Hamilton & Gordon E. Mestler, Mortality and Survival: Comparison of Eunuchs with Intact Men and Women in a Mentally Retarded Population, Journal of Gerentology, 24, 395-411, 1969

- Elizabeth Anderson, ed. Letters of Mozart, Vol. I, Mozart to his Sister (88a) Rome, April 21st, 1770, pp. 191-192, MacMillan, London, 1988.

- Evirati, literally emasculated men, musico, pleural, musici, musician or musicians were alternate terms used in referring to castrati.

- By way of comparison, a female soprano’s range is from middle C to A in the second octave above middle C, (C4 to A5), a boy treble’s voice is from A below middle C to C two octaves above middle C, (A3 to C6) and a countertenor’s range is from C one octave below middle C to F in the second octave above middle C (C3 to C5). From, The Harvard Dictionary of Music, Don Michael Randel, editor, Fourth Edition, Harvard University Press, 2003 and Nicholas Clapton, Moeschi: The Voice of the Castrato, Haus Books, London, 2008, p. 233.

- Falsetto is a vocal technique found in many cultures and dates back to antiquity. In Manuel Garcia’s 1858 paper describing his observations of the vocal folds, he attempted to distinguish their function when singing with the chest-register as compared to singing falsetto. Currently, highly sophisticated techniques employing fiber-optic stroboscopic observations and xeroradiographic – electrolarngographic analysis are possible. The so-called chest voice is equated with first-mode phonation while falsettists and countertenors employ second-mode phonation that depends largely on the contraction of the thyro-arytenoid and posterior crico-arytenoid muscles.

- A CD produced by Pearl (Opal CD 9823) is available including an informative booklet and features transfers of 17 discs that comprise Moreschi’s recorded legacy.

- The movie, Farinelli, was released in 1994 by director Gérard Corbiau, the musical tracks were prepared by workers at IRCAM in Paris (L’Ircam – Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique).

- Naomi André, Voicing Gender: Castrati, Travesti, and the Second Woman in Early-Nineteenth Century Italian Opera, Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Henry Pleasants, Great Singers: From the Dawn of Opera to Caruso, Callas and Pavarotti, Chapter X, Simon & Schuster, Inc. NY, 1981

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD, is a gastroenterologist and Associate Professor Emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He is also a member of the Hektoen International Editorial Board and serves as the President of the Chicago Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2010 – Volume 2, Issue 3

Leave a Reply