James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Figure 2. Title page from Pièces de Viole, 1701

Marin Marais

Figure 1. Marin Marais, 1704

André Bouys

How has medicine been depicted in music? Examples from the operatic stage come to mind: tuberculosis in Verdi’s La Traviata and Puccini’s La Bohème; madness or delirium in the mad scene in Donizetti’s Lucia Da Lammermoor and Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking scene in Verdi’s Macbeth. It is harder to find examples in instrumental music. Bedřich Smetana sought to represent his impaired tinnitus and hearing loss with a piercing sustained high E played by the first violin in the last movement of his string quartet No. 1 in E Minor, “From My Life.” There are those who hear the representation of Gustav Mahler’s irregular heartbeat (probably atrial fibrillation associated with rheumatic mitral valvular heart disease) in the opening measures of his Ninth Symphony. This article presents a unique convergence of medical history and music in a piece written for the viol (viola da gamba) and continuo by the French composer and virtuoso viol player Marin Marais (Figure 1), a contemporary of Johann Sebastian Bach, depicting in music a surgical operation he endured at the age of 64 to remove a stone from his urinary bladder.

Marin Marais (1656–1728) was of humble origins; his father Vincent was a shoemaker.2 In 1667 he entered the choir school of St. Germain-l’Auxerrois and received an excellent musical education. He excelled in playing the viol and by 1675 was playing in the Opéra orchestra of Paris. His musical abilities came to the attention of Louis XIV and in 1679 at the age of 20 he became a member of the Royal Orchestra, the musique de la Chambre du Roy. He received instruction in composition from Jean-Baptiste Lully, who was the director of the Opéra and went on to compose four operas for the Paris stage. He excelled in his ability to illustrate the words of his librettos with unusual harmonies, dissonances, and sound paintings. As a virtuoso of the viola da gamba, Marais’ fame spread throughout France. His remarkable technique allowed him to develop and advance the technical limits of the instrument. Between 1686 and 1725 Marais published five books of pieces for viol and continuo and several suites for two and three viols—a total of 596 pieces.

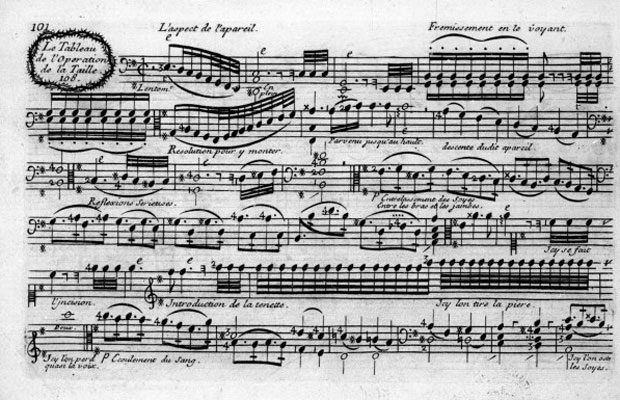

Figure 4. Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille, Les Relevailles, Score 109 Marin Marais

Figure 3. Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille,

Score 108

Marin Marais

It is in the 5th book that he includes a Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille (1725) depicting the stages of an operation for removing a urinary bladder calculus. It is believed that Marais suffered through this procedure at about the age of 64 (1720). He remained in Royal service until 1725 and died three years later at the age of 72. The 5th book was published with a beautifully engraved title page showing two cherubs holding up a screen with the title, Pièces de Viole composed by M. Marais ordinaire de la musique de la Chambre du Roy (Figure 2). In the foreground a third cherub plays a viol along with a bow and several instruments including a theorbo.

Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille (Figure 3) begins with a somber section in the key of E minor and tempo marking Lentem (slowly), freely performed. It is followed by a contrasting lively piece titled Les Relevailles in the key of E major, tempo marking Gay, joyously celebrating the patient’s return to life (Figure 4). The score is annotated in considerable detail, guiding the performer in what the music is attempting to convey. As Joseph Kiefer accurately observes: “The music successfully depicts the apprehension, fear, agitation, and other emotions of the patient as well as the mounting tension of the operation itself, building up to the climactic extraction of the stone.”3 These annotations are listed in Table 1 in French and English.4Les Relevailles is etymologically of particular interest. It refers to an ancient ritual that designates a period after delivery when the mother needs to regain her strength. Historically this period lasted 40 days and may be related to the religious ceremony known as “churching.”5 The recovery period associated with this operation in the 16th and 17th century was typically from 6 to 8 weeks. Interestingly, several contemporary recordings exist in which a narrator recites the annotations over the music, although there is no indication that this was a performance practice in the 18th century.6

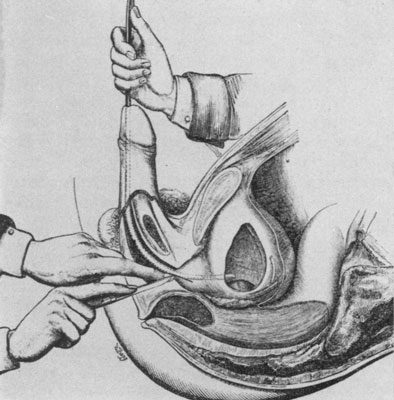

Bladder calculi have afflicted mankind since antiquity. The fact is affirmed by the finding of a stone in the pelvis of a pre-dynastic skeleton in Egypt estimated to be 7,000 years old. Operations for stone were done by Hindu and Egyptian surgeons before the Christian era. Hippocrates advised his followers not to “cut for stone,” as he regarded wounds to the bladder as mortal. Sir Eric Riches in The History of Lithotomy and Lithotrity details the evolution of surgical techniques for bladder stones.7It is likely from the annotation in the score that Marin Marais’ surgical procedure was a lateral lithotomy that involved a left lateral perineal incision (Figure 5). The operation was introduced in Paris at the turn of the 18th century by one Jacques Beaulieu (1651–1714), later known as Frère Jacques and modified by John Jacob Rau (1588–1709).8 Rau’s study of the anatomy led him to perform an incision that reduced injury to the bladder and rectum, resulting in a mortality of 6% in his first 100 and 12% in a second series of 113 patients. In the 1983 journal Minerva, S. Rocchietta speculates that the operation may have been performed by Jean-Baptiste Basilhac (1703–1781) who introduced the “great apparatus” for the extraction of bladder stones.9 Leonard J. T. Murphy in his The History of Urology states that Jean Baseilhac, also known as Frère Côme, was from Lyons and did not come to Paris until 1726, making it unlikely that he would have performed the operation.10Rocchietta further states “the operation could have been performed by some member of the famous family Collot (also Colot), court surgeons who became so famous for the operation that they were simply called ‘the lithotomists.’” Sir Eric Riches notes in his historical review that the Collots were famous lithotomists in France for eight generations. The identity of the surgeon and the exact technique employed is simply not known. However, Marais’ close association with the Court of Louis XIV makes it likely that one of the prominent surgeons associated with the court would have performed the procedure. The annotations included in the score of Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille suggests that the “apparatus” was similar to that seen in Figure 6, illustrating the operation being performed by a surgeon and four assistants and the binding of the patient’s extremities with silk.

Figure 6. The apparatus fromTrait de la Lithotomie, 1698

Figure 5. The anatomy of lateral lithotomy from Practical Lithotomy and Lithotripty, 1863

Claire Tomalin in her biography, Samuel Pepys: The Unequaled Self, provides a vivid account of a similar operation performed in London on Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) in 1658 when he was 25 years old.11 If Marin Marais celebrated his recovery in music, Pepys commemorated the anniversary of his recovery with a special feast, and preserved his stone—said to be the size of a tennis ball—in a special “stone-case” that he had made for 25 shillings.

Surveying the literature on this subject will reveal several sources erroneously stating that Le Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille (1725) describes the operation Marais is depicting as gallbladder surgery. The earliest reference source of this error seems to be the otherwise very scholarly article “Marin Marais’s Pièces de Violes” by Clyde Thompson: “This remarkable piece attempts to depict the horrors of a gall-bladder operation, without the benefit of anesthesia, experienced by Marais around 1720.”12 This error was carried over in a treatise on performance practice by Deborah A. Teplow and in an article previously cited by Joseph H. Kiefer (though this author is clearly aware that the surgery was for a urinary bladder calculus).13,14 Popular Internet sources also perpetuate this error. The first operation performed on the gallbladder to remove stones was a late 19th century phenomenon. The first well-documented cholecystostomy (to incise and close the gallbladder so as to remove gallstones) was performed by John Bobbs of Indianapolis in 1878.15

Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille was one of several pieces Marais designated as pièce de caractère (pieces of character). This was a genre that Marais used with increasing frequency in his instrumental compositions. The 5th book of Pièces de Viole contains an elegy for one of his deceased sons, a moving work titled Tombeau pour Marais le Cadet. Of his 19 children, several became distinguished performers on the viol, and his eldest son succeeded him in the musique de laChambre du Roy. Also of medical interest is a composition appearing in the 4th book of his Pièces de Viole titled, “Allemande L’Asthmatique” that musically seeks to depict the tonal quality of wheezing a century before René Laënnec would invent the stethoscope in Paris.16

Table

| Annotations appearing in Le Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille, Pièces de Viole, Book V | |

| Le Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille | Description of the Operation of the Stone |

| French | English |

| L’aspect de l’appareil | The appearance of the operating table |

| Frémissement en le voyant | Trembling at its sight |

| Résolutions pour y monter | Determination when mounting it |

| Parvenu jusqu’en haut | Climbing in |

| Descente du dit appareil | Climbing out and dismounting |

| Réflections sérieuses | Serious thoughts |

| Entrelassement des soyes entre les bas et les [jambes] | Knotting the silk restrains for arms and legs |

| Icy se fait l’incision | Here the incision is made |

| Icy se fait l’introduction de la tenette | Introduction of the forceps |

| Icy l’on tire la pierre | Then the stone is drawn |

| Icy l’on perd quasi la voix | The voice falters |

| Ecoulement du sang | Blood flows |

| Icy l’on oste les soyes | Then the silks are unknotted |

| Icy l’on vous transporte dans le lit | Then you are taken to bed |

Click on this YouTube link to hear Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille performed by the ensemble Orpheon directed by professor José Vazquez of the Université de musique de Vienne.

Notes

- The author wishes to thank Henri Frischer, MD, PhD and Constance Markey, PhD for their assistance in translating materials referred to in this article.

- Stanley Sadie and John Tyrell, eds., “Marin Marais, Jérôme De La Gorce and Sylvette Millot” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., no. 15 (New York: Oxford University, 2001), 795–797.

- Joseph H. Kiefer, “Lithotomy Set to Music: An Historical Interlude,” Urological Survey 14 (1964): 2–7.

- F. S. Haddad et al., “Marin Marais and his ‘Le Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille,’” Acta Belg Hist Med 7, no. 2 (1994): 66–70. This paper contains the annotations from the score along with English translations used in part in Table 1.

- I am grateful to Ms. Rachel Baker, Director of Education Programs, Hektoen Institute for clarifying the etymology of this term.

- As an example the recording “Marin Marais: Pièces de viole du Cinquième Livre,”accent label (ACC10044), presents the piece with the annotations voiced over the performance in French.

- Eric Riches, “The History of Lithotomy and Lithotrity,” Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 43, no. 4 (October 1968): 185–199.

- J. P. Gamem and C. C. Carson, “Frère Jacques Beaulieu: From Rogue Lithotomist to Nursey Rhyme Character,” The Journal of Urology 161(April 1999): 1067–1069. One author has speculated that Frère Jacques Beaulieu is the subject of the famous nursery rhyme.

- S. Rocchietta, “Musica e litotimia in una composizione di Marin Marais (1656–1728)” Minerva Medica 74 (1983): 2713.

- L. J. Murphy, “Lithotomy and Lithotomists,” in The History of Urology (Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1972), 111.

- Claire Tomalin and Samuel Pepys, The Unequalled Self (New York: Knopf, 2002), 59–64.

- Clyde H. Thompson, “Marin Marais’ Pièces de Viole,” The Musical Quarterly 46, no. 4 (October 1960), 482–499.

- Deborah A. Teplow, Performance Practice and Technique in Marin Marais’ Pièces de Viole (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1986), 29.

- Joseph H. Kiefer, “Lithotomy Set to Music: An Historical Interlude,” Urological Survey 14 (1964): 6.

- W. P. Longmire, Jr., “Historic Landmarks in Biliary Surgery.” Southern Medical Journal 75 (1982):1548–50; J. S. Bobbs, “Case of Lithotomy of the Gallbladder.” Trans. Indiana Med. Soc. 18 (1868), 68–73.

- Sheldon G. Cohen, “Asthma Among the Famous: A Continuing Series,” Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 17, no.1 (January 1996):40–42. Allemande L’Asmatique appears in the second part of Book IV as part of an extended set of pieces titled Suitte d’un goût étranger (Suite for a Foreign Taste).

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 4, Issue 3 – Summer 2012

Leave a Reply