William Albury

New England, Armidale, Australia

While evolution of the modern concept of autism dates from the middle of the twentieth century, evidence suggests that behaviors which are now considered autistic have occurred in the human species since its prehistoric origins (Spikins). The cause of autism is unknown, and its diagnosis can be controversial, but its most extreme manifestations are a perceived lack of social skills, impaired language development, and repetitive, ritualistic behavior to which the autistic individual is highly attached. In the late twentieth century a recognition that these symptoms can also occur in less extreme forms led to an expansion of the concept into an autistic spectrum that encompasses both classic autism and the milder condition known as Asperger’s syndrome. Given the mysterious nature of autism, it is not surprising that in earlier times descriptions of unusual individuals who were regarded as “changelings” or “feral children” often included characteristics similar to those of persons currently diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder. More recently, as space exploration captured the popular imagination in the mid-twentieth century, descriptions of “visitors from outer space” in terms of autistic behavior have become more prevalent.

Although ideas surrounding changelings, feral children, and extraterrestrials developed independently from the concept of autism, the similarities between the ascribed characteristics of these exceptional beings and autistic persons have drawn the attention of the medical community and, interestingly, have appeared in more recent literature describing individuals with autism. Yet while the metaphors used to describe individuals with autism have evolved over time, their consistent focus on the “otherness” of these individuals raises interesting questions about conceptions of normalcy in Western society.

The changeling, the feral child, and the extraterrestrial

The idea of the changeling draws on the ancient folk belief that an abnormal child was not the real child of its putative parents, but a spirit, such as an elf, fairy, or goblin, left in the real child’s stead. Having been abducted from the parents, the true child was raised amongst its supernatural abductors, while the otherworldly child remained (Haffter). Consistent with the more severe manifestations of autism, most changelings lacked typical social behavior. Refraining from talk or laughter, they would cry incessantly, remain silent, or seem to find enjoyment at someone else’s distress. On rare occasions, a changeling might unexpectedly utter a word or two, giving the impression that the creature obstinately refused to speak despite an ability to do so.

Often changelings were described as physically grotesque, but some of them, like some autistic individuals, were said to be of normal appearance and show exceptional ability in a single area such as music or concentrated work (MacCulloch). A well-known historical example of a reputed changeling is the 12-year-old Saxon boy to whom Martin Luther referred in a biblical commentary of 1535 and a discussion with his associates in 1540. As the child was said to be able to do nothing but eat and excrete, Luther regarded it as a mass of flesh animated not by a human soul but by a devil. The situation, he believed, was one in which the devil had acted “to remove a child completely and put himself into the cradle in place of the stolen child” (Miles 30-31).

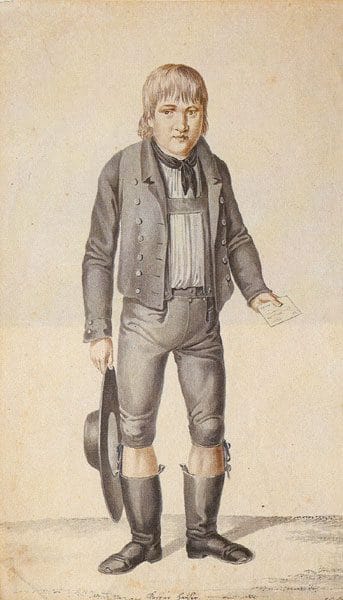

The feral child presents a mirror image of the changeling. In both cases, a child passes between the spheres of the human and the non-human; however, stories of feral children usually involve wild animals—rather than spirits—who adopt the child after it has been orphaned or abandoned by the human sphere. Typically the feral child is a young person who is found living alone in a forest and who shows no signs of having been socialized by humans. The apparently animal-like behavior of such children gave rise to the belief that they had been raised in the wild by wolves or other pack animals (Malson). Generally lacking social skills and language abilities, they often have difficulty integrating into human society after they are taken into care. One of the best documented cases is that of the Wild Boy of Aveyron, who was found in southern France in 1798–99 (Lane).

More recently, stories of space travel and extraterrestrial life have provided new images of otherworldly beings with autistic characteristics. In the mid-twentieth century the celebrated science fiction novel Stranger in a strange land clearly describes a human child raised by extraterrestrials, a modern-day feral child, in terms of autistic characteristics. Orphaned as an infant on Mars, the child of a crew member of Earth’s first expedition to the planet, Valentine Michael Smith is raised by Martians. He eventually returns to Earth 25 years later with the crew of a second expedition. Smith’s unusual behavior, which is normal by Martian standards, includes hypersensitive reactions to visual, tactile, and auditory sensations; extreme literalism and a limited use of language; social withdrawal and absence of facial expressiveness; inability to empathize with or comprehend human emotions; inability to understand the concept of fiction or lying; absence of any sense of humor; and a savant-like memory, flawlessly remembering everything he has read (Heinlein 301).

The otherworldly being as a metaphor

While metaphors involving these otherworldly beings have not always specifically described individuals who would today be considered autistic, they have historically been used to characterize individuals who do not fit into normal human society. According to a report published in 1832, Kaspar Hauser, a young man found wandering in Nuremberg in 1828 after supposedly being raised in a dark cell until the age of 17, exhibited such unusual behavior that observers wondered “whether he should be taken as an inhabitant of another planet miraculously transported to earth” (Feuerbach 84).

Other accounts employ the concepts of both the changeling and the extraterrestrial to illustrate the origin of otherworldly or difficult children. In one of the earliest stories of space travel in English, The man in the moone, the narrator reports that when the inhabitants of the moon detect lunar children “who are likely to be of a wicked or imperfect disposition, they send them away into the Earth, and change them for other children, before they shall have either ability or opportunity to do amiss among them” (Godwin 104, spelling modernized).

As autism became more clearly defined in the late twentieth century, psychologists began to find representations of autism in the descriptions of otherworldly beings within literature. Drawing on the writings of the physician who worked with the Wild Boy of Aveyron for several years (Itard), modern professionals tend to agree that the child showed signs of autistic spectrum disorder (Wing). More broadly, Bruno Bettelheim argued that the majority of feral children are autistic. While this conflation of the two groups was not generally accepted and Bettelheim’s theories on the cause and treatment of autism are now outdated (Albury), he nevertheless was one of the first to draw attention to the behavioral similarities between feral children and children with severe autism.

The renowned British psychologist John Wing, in describing the common perception of autistic children as “Children from another planet” (38), notes their resemblance to the children in the science fiction novel The Midwich cuckoos, who were born in a small village after an extraterrestrial force had simultaneously impregnated all the women of childbearing age (Wyndham). And mental health professionals have often speculated that the half-human and half-alien Star Trek character Mr. Spock—with his high level of functioning coupled with his lack of typical human emotion and savant-like qualities—has been based on individuals with Asperger’s syndrome, one of the milder autisic spectrum disorders (Jacobs).

The metaphorical use of these otherworldly creatures to describe individuals with autism can also be found in Clara Park’s autobiographical account, The siege: A family’s journey into the world of an autistic child. In the first chapter, titled “The changeling,” the author describes her autistic daughter Jessy’s early years, writing that her daughter’s attractive appearance and unusual behavior prompted the thought that “the fairies had stolen away the human baby and left us one of their own” (12). Later she writes of “the eerie feeling we have at times that Jessy is a Martian, a visitor from some pure planet where feelings do not exist” (1986, 90). Park combines these two themes in her epilogue to The siege: “It is like living with a martian. . . . Jessy is our fairy child still, escaped from an alternative universe” (289).

The significance of metaphors

At one level the metaphors of changeling, feral child, and extraterrestrial all identify the autistic person as someone whose defining characteristics are non-human—someone who is wholly “other” (Hacking). They are expressions of the distance and incomprehension that one might honestly feel in attempting to interact with an autistic person, but they are also stigmatizing labels that create their own distancing effect and act as barriers to comprehension. Where such terminology is used affectionately by the family or friends of an autistic person, as in Park’s case, then any stigmatizing effect is probably minimal so long as the metaphor is understood in its original context. But it is more likely to be harmful if given widespread circulation by popular authors or apparently official endorsement by professionals working in the autism field.

In popular culture the metaphors we have considered may have either a positive or a negative valuation. The changeling may be a creature who is ethereally beautiful like Park’s fairy child or one who is grotesque and troublesome like Luther’s devil and Godwin’s wicked lunar babies. The feral child may be destined for greatness like Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome who were suckled by a she-wolf (Howatson 490), or he may be sunken in bestial squalor like the Wild Boy of Aveyron when he was first discovered by French peasants. And the extraterrestrial may be either a benevolent representative of a higher civilization like Valentine Michael Smith and Mr. Spock or a hostile invader bent on destruction like the Midwich children.

When negatively-valued, these metaphors convey a sense of danger and provide reasons why the autistic person should not be integrated into society. On the other hand, when positively-valued, they convey a sense of aloofness and may be used to explain why attempts at integration are unsuccessful: these exceptional people are welcome to be like us, but they have no wish to do so. The first response promotes an active exclusion of autistic people from mainstream society, while the second promotes a passive resistance to measures that might facilitate their social inclusion.

There is no question that autistic behavior differs in many respects from the norm, but the importance placed on these differences can be culturally variable. In most Asian cultures, for example, a typically autistic behavior like the avoidance of eye contact is a relatively minor issue, whereas in most Western cultures maintaining eye contact is an essential feature of social interaction (Argyle et al. 298). For Westerners, then, even if avoidance of eye contact is explained as a disability in biomedical terms, it still remains deviant behavior in social terms (Friedson).

There are other autistic behaviors which are of course more challenging to social expectations, more extreme and less acceptable. But segregating autistic people from the social mainstream deprives both this group and the general public of the opportunity to benefit from mutual desensitization, the phenomenon whereby frequent exposure to something unusual or confronting makes it seem less strange and threatening (Bandura et al.). Such segregation thus tends to make almost all autistic behaviors, and not just the extreme ones, so unfamiliar that they tend to evoke the feeling of “otherness” in onlookers. From this perspective, the stigmatizing metaphors we have discussed are as much symptoms of the relative exclusion of autistic people from society as they are references to extreme forms of autistic behavior.

References

- Albury, W.R. “Metaphorical Dimensions of Childhood Autism.” “Outpost Medicine”: Australasian Studies on the History of Medicine. Ed, Susanne Atkins et al. Hobart: University of Tasmania and the Australian Society of the History of Medicine, 1994. 311-319.

- Argyle, Michael et al., “Cross-Cultural Variations in Relationship Rules.” International Journal of Psychology 21 (1986): 287-315.

- Bandura, Albert et al., “Relative Efficacy of Desensitization and Modeling Approaches for Inducing Behavioral, Affective, and Attitudinal Changes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 13 (1969):173-199.

- Bettelheim, Bruno. “Feral and Autistic Children.” American Journal of Sociology 64 (1959): 455-467.

- Feuerbach, Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von. “Kaspar Hauser.” Lost Prince: The Unsolved Mystery of Kaspar Hauser. Ed. and trans. Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. New York: Free Press, 1996. 73-158.

- Friedson, Eliot. “Disability as Social Deviance.” Sociology and Rehabilitation. Ed. Marvin B. Sussman. New York: American Sociological Association, 1966. 71-99.

- Godwin, Francis. The Man in the Moone: or a Discourse of a Voyage Thither by Domingo Gonsales. Menston, England: Scholar Press, 1971 (reprint of 1st ed. London: John Norton, 1638).

- Hacking, Ian. “Humans, Aliens & Autism.” Daedalus 138.3 (2009): 44-59.

- Haffter, Carl. “The Changeling: History and Psychodynamics of Attitudes to Handicapped Children in European Folklore.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 4 (1968): 55-61.

- Heinlein, Robert A. Stranger in a Strange Land. New York: Putnam’s, 1961.

- Howatson, Margaret C. Ed. The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd ed. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Itard, Jean Marc Gaspard. “The Wild Boy of Aveyron.” Wolf Children. Ed. Lucien Malson. London: NLB, 1972. 89-179.

- Jacobs, Barbara. Loving Mr. Spock: Asperger’s Syndrome and How to Make Your Relationship Work. London: Penguin, 2004.

- Lane, Harlan. The Wild Boy of Aveyron. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- MacCulloch, J.A. “Changeling.” Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics. Ed. J. Hastings. 13 vols. Edinburgh: Clark, and New York: Scribner’s, 1908-1926. 3: 358-363.

- Malson, Lucien. Ed. Wolf Children. London: NLB, 1972.

- Miles, M. “Martin Luther and Childhood Disability in 16th Century Germany.” Journal of Religion, Disability and Health 5.4 (2001): 5-36.

- Park, Clara C. The Siege: A Family’s Journey into the World of an Autistic Child. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1982.

– – -. “Social Growth in Autism: A Parent’s Perspective.” Social Behavior in Autism. Eds. Eric Schopler and Gary B. Mesibov. New York: Plenum, 1986. 81-99. - Spikins, Penny. “Autism, the Integrations of ‘Difference’ and the Origins of Modern Human Behaviour.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (2009): 179-201.

- Wing, John K. “Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Aetiology.” Early Childhood Autism: Clinical, Educational and Social Aspects. Ed. John K. Wing. Oxford: Pergamon, 1966. 3-49.

- Wing, Lorna. “[Review of] Harlan Lane, The Wild Boy of Aveyron.” Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia 8 (1978): 119-123.

- Wyndham, John. The Midwich Cuckoos. London: Michael Joseph, 1957.

WILLIAM R. ALBURY, PhD, is adjunct professor of history in the School of Humanities at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. His principal research interests are the history of science and medicine, the use of medical and cosmological metaphors in political thought, and social history as reflected in works of art. His most recent publications in these areas are: “The ossification diathesis in the Medici family: DISH and other features” (with G. M. Weisz, Marco Matucci Cerinic, and Donatella Lippi) in Rheumatology International, “Medicine and statecraft in The book of the courtier” in Intellectual History Review, and “St Joseph’s foot deformity in Italian renaissance art” (with G. M. Weisz) in Parergon.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 3, Issue 3 – Fall 2011