Frank Wollheim

Sweden

This story tells of two prominent humanists, Jan Gösta Waldenström (1906–1996) and Dag Hammaskjöld (1905–1961), the former my teacher and mentor, the latter an admired icon. Jan and Dag became close friends for life as students in Uppsala in the 1920s when they often met in the same matlag—a food or meal team. In Uppsala, students often belonged to a matlag, where a landlady offered daily meals to a group of about 10 students in her home. As students came from different faculties, this tradition fostered interdisciplinary contacts and friendships.

Jan and Dag came from upper middle class families, both of which had contributed greatly to Swedish culture and society. Jan’s great-grandfather was provinsialläkare (district physician) in Luleå, in the north of Sweden. His grandfather was Johan Anton Waldenström, a professor of surgery in Uppsala. He was one of the very first to operate on an ovarian cyst in the abdomen. His brother was the famous Paul Peter Waldenström. Born in 1838, he had been a high school teacher and priest in the Lutheran state church, and in 1857 founded a religious sect now called Mission Covenant Church of Sweden with over 100,000 active members. He was also a member of the Swedish parliament. Jan’s father, Johann Henning Waldenström, was professor of orthopedic surgery at the Karolinska Institute. One of his scientific achievements was to show the reversibility of amyloid deposits after curing a patient’s osteomyelitis. Three of Jan’s children are now academic physicians. A second cousin, Erland Waldenström, was a well established industrialist and brother of Jan’s wife, Elisabet.

Dag was the son of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, a prominent civil servant, member of the parliament, and Sweden’s prime minister (1914–1917). Hjalmar was a professor of international law and was promoted as county governor in Uppsala in 1907. The family therefore lived at the medieval castle in Uppsala. He was also elected as one of the 18 members of the Swedish Academy and later became chairman of the Nobel committee. Dag’s mother’s maiden name was Agnes Almqvist, and her uncle was the famous Swedish poet and writer Carl Jonas Love Almqvist.

Jan and Dag both received excellent schooling, including some private tutoring. Music, literature, and the arts were natural ingredients of their early years. They were both groomed into the best of European culture, albeit with a conservative flavor. Dag’s father was a strong supporter and friend of the ruling king of Sweden. Dag had to serve (reluctantly?) as tutor for the royal princes attending Uppsala University. Dag and Jan both received extensive schooling in botany and became deeply devoted Linneans for life. Jan always included a visit to a local botanical garden wherever he went on his extensive travels.

Jan Waldenström’s scientific contributions are well known. In 1937 he defended a landmark thesis on a dominant autosomal form of acute intermittent porphyria with high prevalence in northern Sweden. In 1943 he described macroglobulinemia and purpura hyperglobulinemica, later also lupoid hepatitis and the carcinoid syndrome. Lupoid hepatitis was independently described by Henry Kunkel, a leading rheumatologist at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City, and the sufferers were nicknamed “Kunkel-Waldenström girls.” Finally, multiple myeloma became his main clinical interest, and he contributed heavily to the distinction between monoclonal and polyclonal gammopathies.

Dag finished his law studies in Uppsala in 1930, and defended his PhD thesis in Stockholm in 1933. After serving for 10 years as undersecretary to the social minister of finances, he then moved to the staff of the foreign ministry and became an apolitical member of the Cabinet. He never ran for office. His career was based on sincerity, fast and unbiased analysis of facts, and an unusual ability to find acceptance for compromise in difficult conflicts.

The friendship between these two historic figures is documented in letters, some in the Hammarskjöld archive in Stockholm and also in a book by the Swedish author Karl Birnbaum.1,2 The letters date back to 1926. Interestingly, the students exchanged long letters even only a few hours after spending time together—this was before text messages, emails, or Facebook. Common interests in nature, botany, literature, music, and the arts were part of this close friendship.

|

| The angel of the annunciation c.1466-1470 Melozzo da Forlì The Uffizi Gallery, Florence |

Although Jan had religious heredity, it was Dag who was a firmer believer in God. In a letter dated July 12, 1927, Jan writes on their relation:

Now we do not only face responsibility to ourselves and the purpose of our lives, but also towards the friend, and therefore I believe that our friendship will bring me closer to a religious concept of existence than anything else in life . . . . In its highest form our friendship leads to a belief in immortality related to that referred to by Ernst in ‘Schiller’s death’ . . . .1

Both Dag and Jan had a strong emotional attachment to their mothers, whose close friendship in turn was passed on to their boys. Dag’s mother Agnes was often ailing and he was her accompanying support at the castle in Uppsala and also during stays at spas.

On January 2, 1931, Jan sent a postcard to Dag from Florence showing “The Angel of the Annunciation” by Melozzo da Forlì. He wrote:

How was your stay in Fjällnäs? . . . How immensely nice it would be to meet and talk about all [the] curious things we have experienced. Do you remember that we used to refer to an angel in the Uffizi Gallery? Here it is with its wonderful expression: ‘Angelo Annuntiante’ by Melozzo da Forlì. 1

Fjällnäs is the oldest inn in the Swedish mountains, a favorite retreat for Dag. It is still uniquely situated in unspoiled nature, a paradise for hiking and cross-country skiing. Jan was newly married to a cousin once removed and had started his residence in internal medicine.

On April 3, 1953, Jan sent a long letter to Dag congratulating him on becoming secretary general of the UN.

|

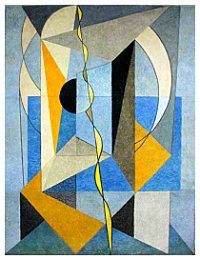

| Mural in the meditation room Bo Beskow UN headquarters, New York City |

From amongst an unusually happy and rich store of common memories many surface at this moment. No doubt you will appreciate that Mother and her pathos for a unified Europe and for appeasement among nations often comes to mind. How happy she would have been to learn that little Dag whom she trusted so much, in such a splendid way continued and complemented the efforts to which her great idol Hjalmar [Dag’s father] devoted so much of his life . . . . Do you remember an evening in June in the tower of the castle in Uppsala when the white beam had just come out[?] We sat there with your matchless Mother and talked about life, and all three of us felt closer than human beings normally are allowed to feel . . . .”1Jan then alluded to their extensive discussions about religion and how only the harmony between nature, culture, and the presence of a being above us makes life worthwhile. He continues, “Then we may again realize what we experienced in King’s Chapel, Cambridge—that the Creator’s world can be wonderful and beautiful if people will understand and follow him.”

Jan often visited colleagues in New York. In 1954, he and his wife, Elisabet, were guests in Dag’s Manhattan residence on 73rd Street and also at the retreat in Brewster, located north of New York City. Jan wrote him a letter from the return to Europe by ship and was looking forward “to hear your talk honoring your great father.” Dag had been elected to replace his deceased father as one of the 18 members of the Swedish Academy. Dag Hammarskjöld was secretary general of the United Nations from 1953 until his untimely death in September of 1961 while traveling to visit Moise Tshombe in the Congo. When Dag was killed in Africa, I remember that Jan dressed in dark and had a white tie, a custom when a close relative passes away.

Art was always close to both Dag and Jan. When Jan visited my parents in Franconia in the late 1950s, he insisted on extensive visits to the most significant works of the 16th century sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider, and for many years we used to exchange Christmas cards with images of his works. Not many Swedes knew about Riemenschneider in those days. When Dag was asked by the Central Bank of Sweden to have his portrait painted, he selected Bo Beskow. The artist and his model became close lifelong friends. Dag acquired a small farmhouse close to Bo Beskow’s home near the south coast of Scania. Later, with Bo’s help, Dag was able to buy a piece of unspoiled coast property, now a Hammarskjöld museum, Backåkra. Sadly, Dag was never able to enjoy spending time there. As secretary general, Dag initiated the creation of a meditation room at the United Nations and commissioned Bo Beskow to contribute the dominating painting, a masterpiece of classic abstract art.

Jan Waldenström was not only a charismatic investigator and teacher, but also a much asked for physician and solver of difficult clinical problems. His friendship with Dag Hammarskjöld and their common cultural interests are a good example of how the humanities contribute to shape the “complete doctor.”

References

- Dag Hammarskjöld Samling. Letters. Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm.

- Birnbaum, K. 1998. Den unge Dag Hammarskjölds inre värld. Ludvika: Dualis.

FRANK A. WOLLHEIM, MD, PhD, FRCP spent two years at the University of Minnesota from 1963–1965. He was professor and chairman of rheumatology at Lund University from 1981–1997. He co-edited the Oxford University Press textbook Rheumatoid arthritis and is a master member of the American College of Rheumatology, where he is currently an emeritus professor.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2011 – Volume 3, Issue 3

Fall 2011 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply