Niyi Awofeso

Perth, Australia

“First we shape our buildings; then they shape us”

Winston Churchill, 1943

Creating the built environment, the surroundings that provide the setting for human activity, draws on multiple disciplines, including architecture and law. Prisons and their many variants are built environments whose intended purpose is punishment, deterrence, rehabilitation and incapacitation (Reasons & Kaplan, 1975). From ancient Rome’s Mamertine dungeon complex (built under the city’s main sewer) to the humane cellblocks of Norway’s modern Halden prison, custodial architecture reveals much about how a society sees fit to discipline and rehabilitate those who contravene penal codes. As expressed in Louis Sullivan’s famous quote, “It is the pervading law . . . of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function” (Morrison, 1998). The architecture of a building thus reflects its function; prisons are no different.

Prison architecture continues to evolve based on each society’s social climate and sociological demands. While early prison design reflected modern imprisonment’s origins in monasteries—a result of the early Church’s stance against the death penalty—modern prison design derives many of its foundations in modern concepts of punishment, such as deprivation of liberty through austerity and lack of privacy. The implications of prison architecture, however, encompass far more than the mere idea of punishment, including effects on the health of inmates and custodial workers. Because security considerations and austere living conditions are the values that drive modern prison development, little attention is paid to the healthy living environments for prisoners. Prison architecture is therefore a likely undervalued but important contributor to prisoners’ health.

History of prison architecture and function

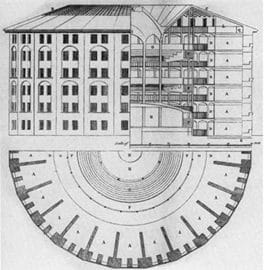

Because the early Catholic Church frowned upon the death penalty and other punishments directed at the body, early prison architecture appears to have been modeled after monasteries. For instance, St. John Climacus documented a sixth century confinement of a monk to a monastery or “house of penitents,” not to be released until there was evidence of divine pardon (Johnston, 2000). In 1298, Pope Boniface VIII published Liber Sextus Decretalium, therein authorizing imprisonment as punishment in the general community. This introduction of imprisonment into law by Boniface VIII replaced brutal punishments such as executions and amputations, which had been practiced since the reign of Emperor Draco in 400 BCE (Morris & Rothman, 1998), but it also likely had an effect on the development of prison architecture. Similarities between architectural plans of NewGate Prison, London (1800, shown above) and the Church of St. Roch, Lisbon (1578), with its cellular design typical of early prison architecture, support the idea that church and monastery buildings served as the template of early prison architecture.

Comparable to the architecture that characterized buildings from 1298 onwards, the earliest prisons were distinguished by thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers, decorative arcading and symmetrical plans. Externally, many of the early prisons resembled fortresses, and some—such as the Bastille prison in Paris—were in fact converted fortresses. Internally, however, the cells were built to resemble the “house of penitents” found in certain monasteries—bare rooms with a solitary window and a door that enabled inmates to be seen by their jailers.

Even modern prison advocates have adopted qualities of monastic architecture, including concepts beyond that of the Spartan cell. Pennsylvania and New York prison design activists implemented a rehabilitation concept that promoted isolated, silent contemplation. Under the penal paradigm of “separate” and “silent” rehabilitation systems, these prisons included chapels for use by the prisoners. Although the cost of staffing such prisons was reduced, the cost of building them was high, as every aspect of prison design, from cells to chapels, had to be built on a per-person basis. The high cost of the construction prevented expansion of this type of system throughout the United States. This prison design, however, became popular in Europe and Australia (Brand, 1975).

More recent prison designs use other models to enforce discipline. In 1785, Jeremy Bentham proposed the panopticon prison design as a disciplinary tool that allows an observer to observe (-opticon) all (pan-) prisoners without the incarcerated being able to tell whether or not they are being watched. Each cell of a prison built using the panopticon design approach would have a window front and back, allowing the cell activity to be lit from behind, while simultaneously obscuring the tower’s windows. The mental uncertainty implicit in prisoners’ not knowing when they are being watched was promoted as a crucial instrument of discipline.

By inducing the inmate in a state of conscious and permanent visibility, panopticon architecture assured the automatic functioning of power by prison authorities. Bentham’s panopticon concept was partially included in the architecture of England’s first modern prison, the Milbank Prison, designed in 1812 by William Williams. Based on records from the Handbook of London, published in 1850, the external walls of the prison formed an irregular octagon and enclosed upwards of sixteen acres of land. Its ground plan resembled a wheel—with the governor’s house occupying a circle in the center—from which radiated six piles of building, terminating externally in towers (Miller & Miller, 1978).

Theories regarding the purpose of punishment underpin the manifest functions of modern prisons and their subsequent design. Punishment is essentially a consequence, delivered after a behavior, which serves to reduce the frequency or intensity with which the behavior occurs. The consequence either provides an undesirable stimulus or removes a desirable stimulus (Lefton, 1991). Popular conceptions of modern penal philosophy generally regard loss of liberty as the sole punishment function of prisons (UK Parliament, 2009), but, as modern custodial architecture reflects, prison design punishes inmates in a variety of ways—emphasizing such values as austerity and incapacitation.

Prison cell dimensions have traditionally been inadequate due to budget constraints. For instance, while the standard 18th and 19th century prison cell was six by eight feet, some were built so small that many inmates were unable to stand upright. Even today, prison walls in most maximum security prisons are designed to mark inmates’ horizons and conceal the justice system’s machinery.

Graham Sykes (1958) framed the punishment function of prisons as comprising the following consequences, or “pains”: deprivation of liberty, deprivation of goods and services, deprivation of heterosexual relationships, deprivation of autonomy, and deprivation of security. Foucault has suggested additional motivations behind current prison design. Commenting on Bentham’s panopticon concept as a form of disciplinary architecture, he writes:

Bentham laid down the principle that power should be visible and unverifiable. Visible: the inmate will constantly have before his eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which he is spied upon. Unverifiable: the inmate must never know whether he is being watched at any one moment; but he must be sure that he may always be so (Foucault, 1989).

Foucault also posited that modern prisons evolved to sequester torture practices from public view. He argued that, as carnival-like public floggings and executions became increasingly unfavorably viewed by the general public, the State substituted the public punishment of the body by the private punishment of the mind. Bentham and Foucault speculated that by embedding punishment systems in prison architecture and institutions rather than meting out punishment openly through public execution or floggings, the State was able to greatly reduce the likelihood of adverse public reaction to the punishment of criminals (Hirst, 1994).

Goffman views prisons as an example of a total institution, defined as “a place of residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time together lead an enclosed formally administered round of life” (Goffman, 1968). From an architectural perspective, Goffman is describing the consequences of incapacitation, which implies the limitation of contact between prisoners and the general community to the barest minimum. In the United States, the prison architecture most conducive to incapacitation takes the form of “supermax” prisons, which are designed for strict solitary confinement and extreme measures of control, inspection, and surveillance (King, Steiner & Breach, 2008). But prisons in general are separated from the wider society, and custodial architecture must be designed to accommodate the inmate’s every need. Everything, from eating to sleeping and from working to exercise, needs to be under one roof. The close interrelationship between prison design and the daily life of the prisoner therefore has important implications for the health of prisoners and prison health workers.

Modern prison architecture and health needs of prisoners

Since the 1950s, prison designers have faced the complex challenge of building prisons that serve many functions in a confined space, and health improvement is usually accorded low priority in this regard. The challenge is clearly greater with old prisons that were designed with different objectives. Israel’s Damon Prison, for example, lodges twenty prisoners per cell in a former tobacco warehouse designed to produce and maintain high humidity (Shimshi, 1999). Such prisons generally endanger human health.

Unfortunately modern prisons rarely incorporate designs that promote the health of inmates or correctional workers. Ideally, modern prison designs should incorporate prisoners’ partial control over cell lighting, adequate ventilation, positive interior distractions, and access to daylight, nature, art, symbolic and spiritual objects. It is also important to create an attractive and inviting space that promotes social interaction and social support. In the United States, maximum control facilities (i.e. supermax high security prisons) hold prisoners in bare cells for 23 hours each day and maintain round-the-clock lighting without prisoners’ control. Such measures have been associated with the aggravation of mental disorders and generally hamper the ability of supermax parolees to transition successfully into society. In addition, supermax custodial officers may experience higher rates of stress, resulting in increased sick leave, medical care for injuries, decreased work performance, and decreased inmate safety due to understaffing (Mears, 2006).

Despite many examples to the contrary, some strides have been made in the construction of health-promoting prisons. Many recently constructed prisons in Europe have adopted architectural designs with salutogenic effects. For example, Norway’s recently commissioned Halden prison possesses what is regarded as the world’s most humane prison design. The exterior consists of bricks, galvanized steel and larch, rather than concrete, which is more aesthetically pleasing. Internally, the design incorporates art murals, jogging trails and a freestanding two-bedroom house where inmates can host their families during overnight visits. This prison was designed to reflect Norway’s humanist philosophy, which posits that repressive prison environments constitute cruel punishment and are not conducive to prisoners’ rehabilitation. Norway’s humanistic philosophy towards incarceration is buttressed by a 20% two-year recidivism rate, which is less than half that of the United States or the United Kingdom. The positive impact of such prisons on prisoners’ health is also affirmed by reviews showing that good prison designs facilitate custodial harmony, improve the wellbeing of prisoners and staff and improve the prospects of prisoners’ rehabilitation (Fairweather & McConville, 2000).

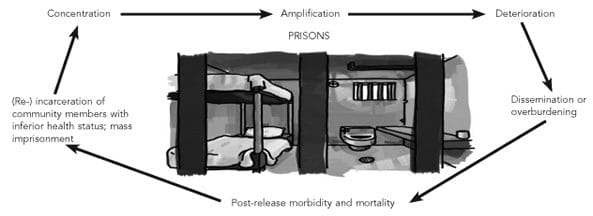

Prisons are important social determinants of health, in the sense that they mediate the vicious cycle of poor health among prisoners. Prisons essentially produce or exacerbate the poor health of inmates through:

- the concentration of unhealthy individuals

- the amplification of unhealthy behaviors

- the deterioration of existing health conditions

- the dissemination of infectious diseases, and

- post-release morbidity and mortality, resulting from health conditions developed or exacerbated during incarceration (Awofeso, 2010).

The prison’s architectural design particularly influences the prison’s role in the amplification of diseases such as tuberculosis, whereby poorly ventilated and claustrophobic shared prison cells and common areas facilitate tuberculosis transmission (Johnsen, 1993).

Making prison architecture health-promoting for prisoners and custodial staff

The United Nations’ document on the minimum treatment of prisoners (1955), section 10 notes the important role of salutogenic prison architecture:

All accommodation provided for the use of prisoners and, in particular, all sleeping accommodation shall meet all requirements of health, due regard being paid to climatic conditions and particularly to cubic content of air, minimum floor space, lighting, heating and ventilation.

However, even though the UN’s document Standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners is over 50 years old, the majority of prisons worldwide, particularly in developing nations, continue to observe this document in its breach. A health-promoting prison need not be more costly than prisons for which security is the prime consideration, and security and health considerations are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In line with the Adelaide statement on health in all policies, government objectives are best achieved when all sectors include health and wellbeing as a key component of policy development (Krech & Buckett, 2010). Prison designs that meet minimum standards for health and well-being of inmates are also more likely to facilitate the rehabilitation of prisoners. However international, regional and national legislation, charters, and rules for the treatment of prisoners needs to be implemented in order to improve the health of inmates.

All new prison design policies should include health impact assessments, and prison design should be modified accordingly. For instance, prisons which allow tobacco smoking in cellblocks need to provide adequate ventilation (Gizza, 1994). Health policies are not sufficient if they solely prevent extreme endangerment, such as murder or suicide. Even though improvements have been made in prison designs that limit the likelihood of patients committing suicide (Atlas, 1989), few nations have followed the precedents set by Norway, Sweden, and Denmark to build prisons which are conducive to the health promotion of prisoners and custodial staff. Many existing prisons were constructed with security as the main consideration. Research on the adverse health implications of existing prison designs will provide an evidence base for restructuring to facilitate improved prisoner well-being.

Original article, peer-reviewed

References

- Atlas, R. (1989). Reducing the opportunity for inmate suicide – a design approach. Psychiatric Quarterly, 60, 161-171.

- Brand, I. (1975). The ‘Separate’ or ‘Model’ Prison, Port Arthur. London: Geneva Press.

- Awofeso, N. (2010). Prisons as social determinants of hepatitis C virus and tuberculosis infections. Public Health Reports, 125, 25–33.

- Fairweather, L & McConville S. (2000). Prison architecture: policy, design and experience. Oxford: Elsevier Sciences.

- Foucault, M. (1989). Discipline and punish – the birth of the prison. New York: Knopf .

- Gizza, L. (1994). Helling v. McKinney and smoking in the cell block: cruel and unusual punishment? American University Law Review, 43, 1091-1134.

- Goffman, E. (1968). Asylums. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Hirst, P. (1994). Foucault and architecture. Architectural Association Files, 26, 52-60.

- Johnsen, C. (1993). Tuberculosis contact investigation: two years of experience in New York City correctional facilities. American Journal of Infection Control, 21, 1-4

- Johnston, N. (2000). Forms of constraint: a history of prison architecture. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press

- King, K., Steiner, B., & Breach, S. R. (2008). Violence in the supermax: a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Prison Journal, 88, 144-168

- Krech, R. & Buckett, K. (2010). The adelaide statement on health in all policies: moving towards a shared governance for health and well-being. Health Promotion International, 25, 258-259

- Lefton, L. A. (1991). Psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon

- Mears, D. P. (2006). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Justice Policy Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010, from http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411326_supermax_prisons.pdf.

- Miller, J. A. & Miller, R. (1978). Jeremy Bentham’s panoptic device. The MIT Press, 41, 3-29.

- Morris, N. & Rothman, D.J. (1998). The Oxford history of prison: The practice of punishment in Western society. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Morrison, H. (1998). Louis Sullivan: prophet of modern architecture. New York: Norton.

- Reasons, C.E. & Caplan R.L. (1975). Tear down the walls? Some functions of prisons. Crime and Delinquency, 21, 360-372.

- Shimshi, S. (1999). 32% make do with one stay – new trends in prison design. Architecture of Israel Quarterly, 39. Retrieved December 21, 2010 from www.aiq.co.il/pages/articles/39/prisons.html.

- UK Parliament. (2009). Role of the prison officer. Retrieved December 20, 2010, from http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmselect/cmjust/361/36104.htm.

- United Nations. (1955). Standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners. Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/treatmentprisoners.htm.

NIYI AWOFESO, PhD, worked as a prison public health officer in New South Wales between 1999 and 2008. He has also worked in prisons in Nigeria and Kyrgyzstan. He is currently a professor of Public Health at the Universities of Western Australia and New South Wales, Australia.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2011 – Volume 3, Issue 1