Annabelle Slingerland

Wouter Jukema

The Netherlands

We would like to thank Dr. Robin Seeley and Rosemary McNally.

Preface

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are now so routinely diagnosed and treated that we rarely consider their origins. However, this distinction did not officially exist until it first appeared in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) in 1965. In retrospect, as this manuscript attempts to show, both types have continued to gain increased recognition since the 1950s, although not under those names. The subject of this piece, “The Song of Diabetes” (1952) celebrates the introduction of insulin therapy in 1922, which enabled otherwise terminally ill patients to survive. Those cases would now likely be characterized as type 1 or insulin-dependent diabetes. The Song also describes the patients who could survive with just changes in exercise and diet. Today they would be diagnosed with type 2 or insulin-independent diabetes. Behind the Song’s scenes, however, resonates the silence of patients, still suffering as they lived with the uncertainties of treatment and fear of complications, and the physicians, tracking the trail of diabetes as a chronic disease. Ironically, the piece chronicles not only the survival of the patient, but also the survival of the disease itself, as treatment of the disease and its complications extends its course. Lifting the veil on the Song’s last half century may shed light on both the Song’s historic contours and how we live with this disease today.

|

| Fig. 1: The waiting room

|

Hiawatha and diabetes share a song

On June 7, 1952, at the banquet of the 12th Annual Meeting of the American Diabetes Association in Chicago, the speaker, Dr. Cecil Striker, recited a poem, “The Song of Diabetes,” that playfully evoked one of our most common medical maladies. He declaimed it using a loose variant of the traditional trochaic Kalevalean tetrameter: each line repeated four times the pattern of double stressed and elongated syllables followed by unstressed and shortened syllables. It therefore mimicked the rhythm and meter of the famous “Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1855.

In the office of the doctor,

In the sanctum of the specialist,

Sat the diabetic patient.

Seven cardinal symptoms had he,

Seven means of recognition,

High blood sugar, malnutrition,

Nagging weakness, all these had he,

Polydipsia, polyuria,

Polyphagia, glycosuria,

The story of diabetes is still recognizable today, and life with diabetes remains full of worries and plagued by complications. Nevertheless, lives have been greatly improved by better understanding of the disease and, for some, by the use of insulin.

Basic therapy is diet,

Insulin when indicated,

Some there are who need no insulin:

Diet only may control them,

Magic savior is insulin,

For those others who require it.

Before the advent of this “magic savior,” patients seen as insulin-deficient were put on strict low-calorie diets to conserve their scarce endogenous insulin and survive for a few more months. In 1922 researchers discovered the panacea, injecting exogenous insulin. Banting, Best, Collip, and McLeod developed it further. For the first time, afflicted patients could gain weight and survive beyond months and into years. Exogenous insulin transformed endangered lives controlled by strict diets into lives with less stringent diets. Lives could be controlled by syringes and were far less endangered. Gradually new regimens of treatment were developed, often based on insulin therapy but also with renewed attention to the role of diet.

In time scholars recognized a type of diabetes that allowed patients to loosely follow the original regimen and still survive for many years. By 1936 Sir Harold Himsworth had already noticed and described—just as others before him—patients who seemed not so much deficient in endogenous insulin, as resistant to it. Three years later he expounded his ideas in the Goulstonian lectures (published in the Lancet). He also urged Dr. E.P. Joslin to inform the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service about the impending epidemic of this new type of diabetes. In 1946 Dr. Joslin indeed received permission to investigate this public health threat. Yet by 1949 the alarm bells had still not been heard at the Royal College of Physicians in London, where the menace would fail to find acceptance until the 1970s. In that decade scientists learned about insulin sensitivity, resistance, and how to measure them. Only by 1993 would these concerns be met and earlier findings reiterated in the 10-year Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Report. Finally heard, the situation would produce a medal reading “ ‘I told you so’, E.P. Joslin.” Winston Churchill compared Himsworth’s achievement to the victory at El Alamein in Egypt that marked the turning point in World War II. He intriguingly added: “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end, but it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” But to implement treatment, teamwork between physician and patient was pivotal.

Follow faithfully your orders,

Comrade makes, of diabetes,

Working with it, not against it,

Thus avoiding psychic conflict,

|

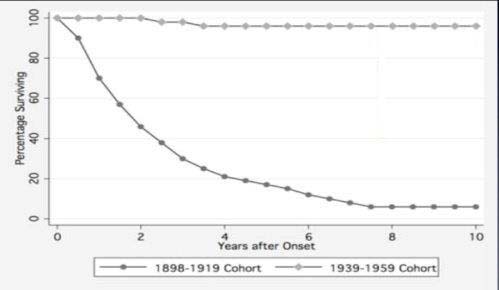

| Fig. 2: Survival rates for diabetes |

By the time of the banquet, Dr. Priscilla White, Joslin’s co-worker, was putting all her efforts into the so-called “transformational experience,” in which she guided patients through Joslin’s Diabetic Manual and Diabetic Patient Handbook. She also worked with “educational wandering nurses,” now best compared to Diabetes Nurse Educators. This approach refocused the diabetes world to view diabetes not as a death penalty but as a life-sentence. They could now prepare for the possibility of a chronic illness.

Life expectancy is lengthened,

Yes assured is normal living.

Life would indeed be prolonged, and many patients who followed the rules of the game would now lead longer, more normal lives. Yet longevity would have its price. Life would still be far from normal, especially once the dreaded complications kicked in: blindness, gangrene, kidney failure. To date, 347 million people have suffered from diabetes worldwide and diabetes is number one in chronic sequelae. Many patients now manage their diabetes as a long term illness, even though secret killers still lie in wait. We thus have entered what doctor and historian Feudtner called an era of “transmutation.” In transmutation, a disease does not become extinct or eradicated, such as smallpox. It does not become a substitute as cancer is for infections either, nor is it relocated or exported like cholera and tobacco-related illness. It simply endures. Thanks to medical interventions, the disease no longer followed its natural course, resulting in the patient’s death. Instead however, treatment kept both the patient and the disease alive! Today, treatment typically starts with diet, steps up with tablets or insulin, and addresses newly arising problems with further medication and medical devices or transplantation. Examples include macro- and micro-vascular disease, deteriorating eyesight and kidney function, vulnerability to infections in wounds that will not heal, and nervous system disorders such as numbness, which causes the body’s alarm system to fail. The disease gets another lease on life along with the patient. This was possible not only while the ultimate goal of “curing the disease” was no longer within easy reach, but also in an era in which for society as a whole, as Einstein stated, the perfection (perfecting) of means (devices, medication, machines) prevailed and other modes of research boomed.

In Chicago at the 12th Annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association, attendees might have felt the vibrations of the time. In the 1940s doctors had become almost assembly-line prescribers of the new panaceas that now came in different flavors, including different types of syringes, insulin and glucose measurement tools. Physicians were eager to extend their horizons, enrich their knowledge and share ideas at such conferences. But at the same time, the tradition of large epidemiological undertakings such as the Framingham Heart study suggested a multi-factorial origin: genetic predisposition, as well as behavioral and external risk factors. Such predispositions could reach epidemic proportions in the increasingly affluent society. Examples included the idea of a thrifty phenotype as in the Barker hypothesis as well as the Social Theory of disease that became influential in the mid-seventies featuring the “Western” diet as the root cause. The powerful statistical associations later identified patients who were running the risk of developing full blown diabetes, yet they still could not prove a causal link and eradicate the disease. The approach of tackling external influences was met, as in Striker’s Song, with an equally multi-factorial model as practiced in Joslin’s Diabetes Center and still followed by many clinicians today. If awards were to stimulate further great works, it was appropriate to award the Banting Medal to the many dedicated physicians and researchers who have done so much to ease the plight of the diabetic patient and taken modern therapy to its current heights. Yet much remains to be done, discovered, and implemented, to bridge the gap between the past and the present, between physician and patient.

References

- Dr. Cecil Striker, The Song of Diabetes, (Dietrich von Engelhardt ed., Diabetes, 27).

- Henry Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha. (New York, USA: Hurst and Company, 1898).

- Dietrich von Engelhardt ed., Diabetes, Its Medical and Cultural History: Outlines, Texts, Bibliography (Berlin/ Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1989).

- Winston S. Churchill, The End of the Beginning (The Mansion House, London, UK: November 10, 1942), in: Winston S. Churchill, Robert Rhodes James ed. (His Complete Speeches, 1897-1963 (New York, USA: Chelsea House Publishers / R.R. Bowker Company, 1974).

- Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War Volume 4, The Hinge of Faith, 1950 (New York, USA, Rosetta Books LLC, 2010). Electronic Version.

- Chris Feudtner, studies in Social Medicine edited by Allan M. Brandt and Larry R. Churchill, Bittersweet: Diabetes, Insulin and the Transformation of Illness, (USA, The University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- Robert Tattersall, Diabetes: the Biography, (New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2009). E-book.

- Joslin Diabetes Center, (http://www.joslin.org/about/history.html 28 February 2014).

- World Health Organization, Non-Communicable Diseases Global Monitoring Framework, ‘NCD Targets and Indicators 2011, http://www.who.int/nmh/global_monitoring_framework/en/index.html 28 February 2014.

- World Health Organization, (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ 28 February 2014).

- Albert Einstein, Out of my later years, (New York, USA: Philosophical Library/ Open Road Integrated Media, reprint 2001 of the original 1956). E-Book.

- Gerald M. Oppenheimer, Becoming the Framingham Heart Study 1947-50, 602-10, (American Journal of Public Health, 95(2005).

- David Barker, Mothers, Babies and Health in later life, in: Tommy Bengtsson ed., Perspectives in Mortality Forecasting, volume 5, 9-29(Stockholm: Swedisch Social Insurance Agency, 2006).

- G. Rose, Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease, 1847-51, (British Medical Journal 282, 1981).

- American Diabetes Association (http://professional.diabetes.org/Congress_Display.aspx?TYP=9&SID=315&CID=75413 and http://community.diabetes.org/t5/The-Watering-Hole/Songs-with-diabetes-meaning-to-you-in-some-way/td-p/461539 28 February 2014).

ANNABELLE S. SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR, earned her medical degree from the University of Amsterdam; Public Health, Health Services Research and Genetics from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. She has worked and collaborated internationally, and (co-) authored research articles in high impact medical journals.

J. WOUTER JUKEMA, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC, earned his medical degree as well as his PhD from the University of Leiden where he is Professor of Cardiology and the Chairman of “Leiden Vascular Medicine”. He (co-)authored numerous articles in highly ranked journals, guided many PhD-students and took part in various (inter)national committees.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2015 – Volume 7, Issue 1

Winter 2015 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply