Göran Wettrell

Lund University, Sweden

In December 1898 Dr. Maude Elizabeth Abbott, assistant curator at the medical museum of McGill University in Canada, was sent to study museums and other institutions in Washington, D.C. In Baltimore she met Dr. William Osler, professor of medicine and one of the founders of the Johns Hopkins Medical School. During a ward round at the hospital she accidentally crushed her finger in a door and aroused the sympathy of Osler, who showed her the pathology department, gave her important reprints, and invited her to dinner. With twelve other young doctors she also participated in a subsequent “students’ night,” discussing medical classics and points of interest and difficulties during the week’s clinical work. Osler told Abbott that there was a great opportunity at the McGill museum. It was a great place, he said, and advised her to read an article in British Medical Journal on “A Clinical Museum.” He described a museum in London for teaching and presented her with “Pictures of life and death together.” As she would later note, this conversation planted the seed for most of her future work.

The pathology museum of McGill University

The oldest faculty at McGill was its medical school, which was organized from 1823-24 as the Montreal Medical Institution in the tradition of the Edinburgh school. It soon became an active and respected teaching institution where clinical observation at the bedside was combined with findings at autopsy. As early as 1824 one of its founders, the internist A. F. Holmes, published a classic autopsy study on “An unusual case of malformation of the heart.”

The specimen, preserved in the McGill museum, later caught the interest of both Osler and Abbott. In early 1870s Dr. R. P. Howard furthered the clinical and intellectual atmosphere at McGill, opening the door for the advancement of the young doctor Osler, who soon became professor of medicine and pathology. Working for a decade at the Montreal General Hospital, he performed almost 800 autopsies. With his work he expanded the collection of well-prepared, interesting specimens that were fully described in the hospital records and often published in local proceedings, reports, and foreign periodicals.

The start of Maude Elizabeth Abbott’s medical career

Denied admission to McGill Medical School, Abbott began her medical career at Bishop’s Medical College in Montreal. She received her medical degree in 1894 with prizes for the best examination. After graduation she went on a postgraduate study-tour in Europe, staying mainly in Vienna and focusing on internal medicine and pathology. By 1896 she was back in Montreal where she set up a practice in internal medicine mainly treating women and children. Interested in anatomy and pathology, she also worked at the Royal Victoria Hospital, reviewing case histories of patients hospitalized with heart murmurs but no heart disease. In 1899 she published an article entitled, “On so-called functional murmurs.”

William Osler’s support of Maude Abbott

Focused and energetic in her role as assistant curator of the McGill pathology museum, Abbott set about cataloging and classifying the disarrayed museum collection. During her early work she found a remarkable heart specimen—a three-chambered heart with the pulmonary artery given off from a small supplementary chamber. However, the specimen was preserved without any accompanying information. When asked about it, Osler remembered the specimen perfectly because it had been demonstrated on several occasions as the so-called Holmes’s heart, first reported in 1823.

Osler’s interest in the museum was further renewed when he visited the museum in 1904. Abbott was further stimulated by finding two volumes of Osler’s postmortem notes from the Montreal General Hospital Records which correlated the clinical data with the autopsy findings.

Abbott began teaching informally at the medical museum in 1901, later instructing groups of medical students on a weekly rotation that became part of the McGill Medical School curriculum in 1904. Osler helped Abbott raise funds and publish a catalogue of the museum specimens. He moved to England in 1905 as Regius Professor at Oxford, and in 1906 co-founded with Abbott the International Association of Medical Museums. Abbott would later become the Association’s first international secretary.

Abbott and Modern Medicine

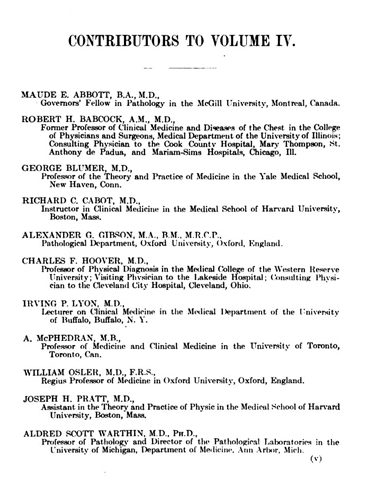

In 1905 Osler invited Abbott to write a chapter on congenital cardiac disease in his multivolume work Modern Medicine and suggested that the subject be analyzed statistically. Abbott worked for two years on the project and completed a chapter of 102 pages on 412 cases of congenital malformed hearts, which was published in 1908. In the second edition, published in 1915, the number of cases increased to 631.

Abbott’s chapter reviewed embryology, etiology, clinical findings, and outcomes of simple and complex heart defects, including descriptions for such conditions as rhabdomyoma of the heart and aberrant chordae tendineae in the left ventricle giving rise to murmurs. Even today it provides much useful clinical information with its reference to cases previously published by Thomas Peacock, Carl von Rokitansky, and many others. It highlighted the difficulties in establishing a scientific and practical classification of malformed hearts, and finally referred to a grouping “on mixed principles.”

Osler was greatly impressed with Abbott’s work, calling it a “good article, one of such extraordinary merit and by far and away the best thing ever written on the subject in English, possibly in any language. For years, it will be the standard work on the subject.” He commented in a postscript that he had “but one regret, that Rokitansky and Peacock are not alive to see it.”

Abbott’s Atlas and legacy

Abbott continued to do research and publish and became internationally famous for her work on congenital heart disease, which she presented at medical meetings in Europe and the United States. Near the end of her career, in 1936, she published her atlas on the pathology and clinical features of more than one thousand cases of congenital cardiac disease. At the time the classification was based on the physiology of altered circulation induced by the defect (first acyanotic group, second group of cyanosis tardive-terminal reversal of flow, and third cyanotic group). In her textbook Congenital Malformations of the Heart from 1947, Helen Tausig concluded that Abbott’s classification had a sound anatomical basis but was of no help in the clinical analysis of congenital cardiac malformations. In her atlas, Abbott coined and discussed the “Eisenmenger complex,” but the concept of pulmonary vascular obstructive disease had not at that time been developed and thus the discussion about cyanosis was complicated.

The publication of Abbott’s Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease in 1936 marked the culmination of the first era, the pathologic anatomy era, of pediatric cardiology. It became the basis for the next step, that of expanding diagnostic techniques and surgery.

In 1928 Maude Abbott wrote about her first meeting with William Osler in Baltimore: “He quietly dropped the seed that dominated all my future work . . . [the] museum work was very demanding and seemed at first a dreary and unpromising drudgery, but as Dr. Osler had prophesied, it blossomed into wonderful things.”

References

- Abbott, Maude E. Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease. New York: The American Heart Association, 1936.

- Abbott, Maude E. and Sir William Osler. Memorial Number. Bulletin No IX of the International Association of Medical Museums. Toronto: Murray Printing Co, 1926.

- Neill, Catherine A. and Edvard B. Clark. The Developing Heart: A History of Pediatric Cardiology. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995.

- Osler, William and Thomas McCrae. Modern Medicine Its Theory and Practice. Philadelphia and New York: Lea and Febinger, 1908.

- Taussig, Helen B. Congenital Malformations of the Heart. New York: Commonwealth Fund, 1947.

GÖRAN WETTRELL, MD, PhD, FLS, is an Associate Professor and Senior Consultant in Pediatric Cardiology and Pediatrics at Lund University, Sweden. Dr. Wettrell’s main interest are molecular genetics in cardiology and primary arrhythmia, especially Long QT Syndrome. His other interests include male choir singing and the history of pediatrics.

Leave a Reply