Florence Gelo

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

All Alone, 2006, Deena Gu (Courtesy of the artist), watercolor on silk, 40 x 32 in.

Three works by artist Deena Gu, All Alone, Blue and Blue, and Resurrection are examples of non-representational paintings in which an artist’s emotional journey was embodied in paint.

All Alone greets me with the quiet dignity and loneliness familiar to those who’ve ever harbored a shattered heart. It is a hazy landscape with a mass of mossy green-leafed trees and ground cover, and a pale blue sky with narrow strips of white cloud. Standing solo in the lower right corner, a tree, prominently painted with bare, tendril-like branches. The painting is unique in the way it bridges Gu’s classical Chinese training with western approaches to art. Intricate black brushstrokes of the barren tree reveal the restraint and discipline of Gu’s early work with classical Chinese technique, while the depth and atmospheric perspective seen in the landscape surrounding the tree reflect her training at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

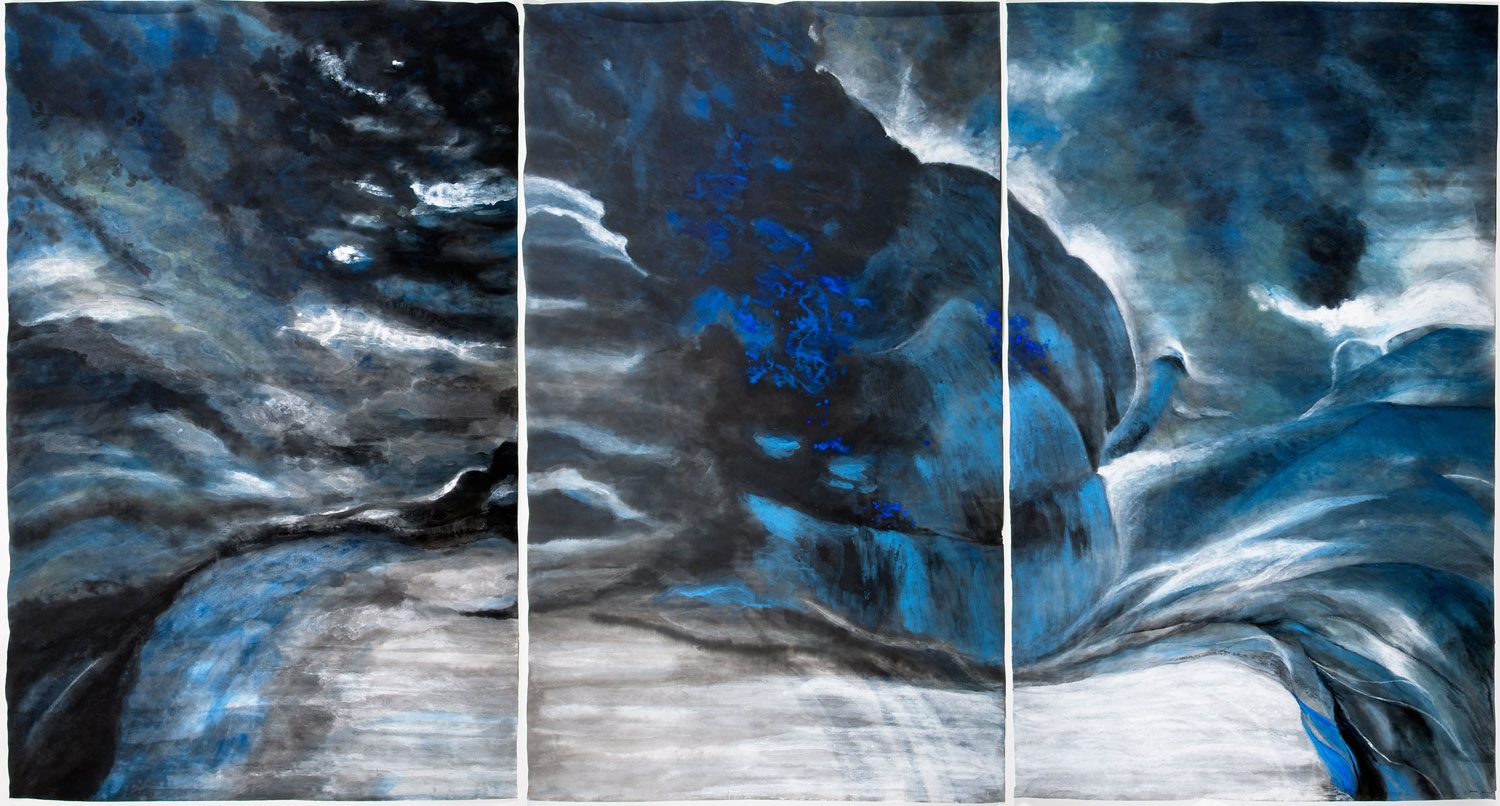

In All Alone, the barrenness of the tree captures the experience of loss as well as it could ever be captured. But a deeper look at the surrounding green landscape, two other trees and warm sky suggest that loss can exist within a context of health, beauty, and peace. It reminds the viewer that what remains of life may feel diminished but one can arrive at a place of peace. The death of Deena’s mother in 2012 had a profound impact on her work. Although she continued to be inspired by nature, she largely abandoned representational imagery and began painting in a more abstract manner. The painting Blue and Blue (2014) was created for Gu’s exhibition at the Woodmere Art Museum and dramatically illustrates this change. Monumental in scale, this triptych painting is composed with intense color, movement and energetic brushwork that exudes raw energy and passion.

Blue and Blue, 2014, Deena Gu (Courtesy of the artist), watercolor on paper, triptych, 82 3/4 x 176 5/8 in. overall

Resurrection (2014) is a vertical watercolor on rice paper that was painted with focused intensity and emotional depth. A testament to her “dear friend” and “second mother” Deborah, the painting attests to Deborah’s emotional journey toward death and to Gu’s own grief and the solace she acquired through her religious faith. Thinking of Deborah daily, Gu began to paint a year after Deborah’s death, making several small studies. The painting took three months plus an entire summer to complete. Gu changed the composition many times, remembering Deborah’s generous, cheerful self and the slow process of her death.

Music had always been important to Gu—”[life] without music is a body without blood,” she says. Now, as she sought to paint the experience of Deborah’s death she found her inspiration in the symphonies of a composer that she had discovered through Deborah herself: Gustav Mahler, more specifically his Symphony No. 2 known as “Death and Resurrection.”

Resurrection, 2014, Deena Gu (courtesy of the artist), watercolor on rice paper, 35 in. x 60 in.

Mahler’s inspiration for Symphony No. 2 came from music that Mahler heard at the funeral of Hans von Bülow. “It’s a massive and utterly awe-inspiring work, which begins with an often-terrifying funeral march and ends, more than 80 minutes later, with a blazing choral hymn celebrating the ultimate rebirth of the spirit. The adjective ‘life-changing’ is overused to describe many things, but Mahler’s Second genuinely has that kind of transformative power.”1 Just as Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 begins with a funeral and ends with dying and resurrection, Gu’s Resurrection makes visual this trajectory towards eternal life.

Though Deborah sparked Gu’s initial interest in Symphony No 2, it was not until after Deborah’s death, when Gu was given tickets to the Philadelphia Orchestra to hear the Symphony live, that the music “spoke to her.” She recalled Deborah, a concert pianist, playing each movement from the symphony, and discovering new meaning. Deborah engaged Gu with stories of the composer’s life emphasizing Mahler’s lifelong preoccupation with death and suffering. Mahler knew intimately the agony of loss early and throughout his life, beginning with the deaths of five of his younger brothers; later a sister would die in an accident, a favorite younger brother from a prolonged illness, and another sister from a brain tumor; still later, both Mahler’s parents, his oldest sister, and his beloved 5-year-old daughter, Maria, would die.

Deborah provided background about Mahler’s symphonies and shared her passion for the Second, or “Resurrection” Symphony. She instructed Gu to read the libretto and to listen over and over again to the music, asserting that there is much more to a piece of music than what one first hears, unless guided.

Gu listened to the Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 fifty or sixty times while painting Resurrection, transforming the metaphysical into pictorial imagery. The symphony brought her closer to Deborah and echoed her feelings of loss. Sound melded into paint, drama infused brushstroke, sorrow incarnated in color as Gu painted her grief with passion, to the soundtrack of a 200 voice chorale and orchestra conducted by Leonard Bernstein. Gu “[I] spread . . . paint on canvas . . . and let [it] sing as loudly as I could.”2 Here we find the visual artwork, Resurrection, compatible with the largesse of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2.

Gu captured on canvas the bleak grieving, its weight as it loops, twists, shifts, and turns back on itself and, finally, the slim movement of hope and confidence, depicted as a slender and delicate stroke of white paint.

Near the conclusion of the symphony, a beautifully orchestrated voice sings “I am from God and will return to God.” Death is left behind, and now, a new beginning. On the canvas, with an upward stroke of Gu’s brush, an angel ascends.

I wish for the two paintings, Resurrection and All Alone, to hang on the museum wall side by side since it is in All Alone that Gu visualizes the balance of energies, of loss and acceptance, and the still, quiet, successful resolution of grief, or accommodation to its vestiges.

I thank Hildy Tow, Curator of Education and Sally Larson, Deputy Director for Collections and Registrar of the Woodmere Art Museum for their generous support.

References

- Albert Imperato. Resurrection: Why We Need Mahler’s Second Symphony on the 10th Anniversary of 9/11 09/02/2011 04:29 pm ET | Updated Nov 02, 2011 HuffPost Arts & Culture. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/albert-imperato/mahlers-resurrection-new-york_b_946006.html

- Kandinsky, W. (1910). Concerning the spiritual in art. Courier Corporation.

FLORENCE GELO is a medical humanities and behavioral science educator. She directed and produced “The HeART of Empathy: Using the Visual Arts in Medical Education,” and uses the visual arts as a teaching tool to enhance clinical skills. She has published numerous articles in professional journals about illness, death and dying.

Leave a Reply