Nereida Esparza

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

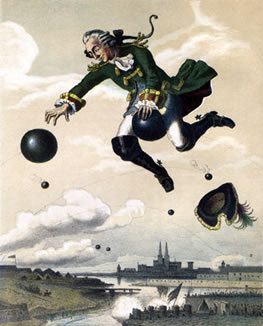

| Münchhausen rides a cannonball August von Wille (1828–1887) |

Munchausen syndrome is a severe psychiatric disorder described in the DSM-IV. In 1951 Dr. Richard Asher named the illness after Baron Munchausen (full name Karl Friedrich Hieronymus, Freiherr von Münchhausen, 1720–1797).1 The German-born baron served in the Russian army until 1750. On his return from the army he was known to tell tall tales of his adventures. These adventures included riding cannonballs, traveling to the moon, and other such fantasies. According to Dr. Asher’s description, a patient with Munchausen syndrome (MS) feigns illness or psychological trauma, invents symptoms, or even tampers with laboratory collections of specimens to draw both sympathy and attention onto themselves.

Dr. Roy Meadow was the first to describe Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MBP), which was based on the psychiatric disorder known as Munchausen syndrome.2 His reputation as a pediatrician was rewarded with knighthood in 1998, but within seven years his career plunged, and his name was struck from the medical register. Meadow’s reputation has since been restored, but his disorder’s acceptance in the medical field remains controversial. Meadow’s sudden rise and precipitous fall forces us to question the ethics of using unsubstantiated mental disorders as legal evidence as well as the impact such a mistake should make on the reputation of a long-term practitioner.

Meadow’s rise to fame

Dr. Roy Meadow was born in 1933 in Wigan, Lancashire, completed his medical education in Oxford University and practiced as a general pediatrician in Banbury. In 1970 he became a senior lecturer at Leeds University. First described by Meadow in The Lancet (1977), MBP is now included in the DSM-IV as a “factitious disorder by proxy” in Appendix B,3 which includes disorders for which more definitive information and research was deemed necessary before inclusion in the manual. Like in MS, patients suffering from MBP feign illness or psychological trauma, invent symptoms, or even tamper with laboratory results in another individual to draw both sympathy and attention onto themselves.4 The following are listed as the criteria for the disorder:5

1. Intentional production or feigning of physical or psychological signs or symptoms in another person who is under the individual’s care.

2. The motivation for the perpetrator’s behavior is to assume the sick role by proxy.

3. External incentives for the behavior (such as economic gain) are absent.

4. The behavior is not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

After his recognition of MBP in 1977, Dr. Meadow was appointed to the chair of pediatrics and child health at St. James’ University Hospital in 1980. Meadow, and MBP, rose to prominence by 1993. He became one of the most influential and respected pediatricians of his time, elected president of both the British Pediatric Association and the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health.6

From bedside to courtroom

Dr. Meadow’s knowledge of MBP made him an influential pediatrician in the area of child abuse, and throughout the 1990s he was called as a witness to court trials where his expert opinion led to several mothers being convicted of murder. In other situations, children were forcibly removed from their parents’ care. He was a key witness in the high profile trial of Beverly Allitt, a nurse accused of murdering four children and harming nine others. After Meadow gave his expert testimony, Nurse Allitt was found guilty of the charges against her and sentenced to life in jail. To many, this was a vindication of Meadow’s theory on MBP, and he was knighted in 1998 for his work and contributions to child welfare.

Controversy begins: the Sally Clark case

Serving as an expert witness in several trials later steered heavy scrutiny and controversy to the well-known pediatrician. Many of these trials concerned previously diagnosed SIDS deaths, particularly when more than one death had occurred in a family. Dr. Meadow’s theory suggests that some SIDS deaths are cases of child abuse reflective of MBP. In fact, the following statement is considered his rule of thumb and is often termed Meadow’s law: “One sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious, and three is murder, unless proven otherwise.”6

The first of these trials was that of Sally Clark—a lawyer who had lost two children to SIDS. The first was her elder son Christopher at 11 weeks, the second Harry at 8 weeks of age. During the trial, medical opinions were divided on whether these deaths were natural. Meadow served on the side of the prosecution, giving testimony that would later fuel the controversy on MBP. During his testimony he gave evidence that the odds of two SIDS deaths occurring in the same family were 73 million to one. Mrs. Clark was given a guilty conviction and sentenced to life in prison.

Sally Clark appealed her conviction twice, first in 2000 and again in 2002. She won the second conviction and was released from prison. The statistical figure given by Dr. Meadow became the center of the controversy. His claim was disputed by the Royal Statistical Society. The president of the society wrote to the Lord Chancellor stating that there was “no statistical basis” for this figure. Once genetic and environmental factors were taken into consideration, the odds of a second SIDS death were stated to be closer to 200 to one. After the second appeal, the opposition spokesman for health, Lord Howe, described MBP as:

One of the most pernicious and ill-founded theories to have gained currency in childcare and social services in the past 10–15 years. It is a theory without a science. There is no body of peer-reviewed research to underpin MBP. It rests instead on the assertions of its

inventor. When challenged to produce his research papers to justify his original findings, the inventor of MBP stated, if you please that he had destroyed them.7

Although Dr. Meadow was to stand by his evidence, he later admitted to having been insensitive, particularly when comparing the odds of both boys’ deaths to those of four different horses winning the Grand National in consecutive years at odds of 80–1.

Other cases, continued controversy

In 1998, Dr. Meadow served as key witness in the trial of Donna Anthony, accused of the death of her 11-month-old daughter Jordan in February of 1996 and her 4-month-old son Michael in March of 1997. She was sentenced to life imprisonment based on the prosecution’s accusation of Ms. Anthony’s attempt to draw attention to herself. Her first appeal in 2000 was unsuccessful.

In 2002, Angela Cannings was wrongfully convicted of the murder of her two sons, 7-week-old Jason who died in 1991 and 18-week-old Matthew who died in 1999, both presumably of SIDS. A previous child of Cannings, 13-week-old Gemma had also died of SIDS in 1989, although her death was not part of the trial for murder. Based only on her suspicious behavior, Cannings was convicted to life imprisonment for having smothered her children. The prosecution stated that there was no genetic predisposition to SIDS in the family. Meadow served as key witness, testifying that Cannings was suffering from MBP. Meadow stated to the jury that the children could not have died of crib death since they had been previously healthy—a contradiction to other expert opinions regarding the deaths as typical presentations of SIDS. He also claimed the double death was extremely unlikely, though he did not present statistical figures. A guilty verdict was handed by the jury.

Sally Clark’s successful appeal in 2002 began to grow controversy around Meadow and his testimonies. In June of 2003, Meadow once again testified in a child abuse case, this time against the pharmacist Trupti Patel, accused of the death of three of her infants. Patel was found not guilty. Solicitor General Harriet Harman barred Meadow from court work, alerting prosecution lawyers of the criticism to Meadow’s evidence.

In December of 2003, the Cannings conviction was overturned. Despite having lost a prior appeal, the case was brought once again to appeal based on the results of Clark and Patel. New evidence demonstrated that the paternal ancestors of Cannings had lost an unusually large number of infants from unexplained deaths, plausibly establishing a genetic predisposition to SIDS.

Following the Cannings case, 28 cases were referred to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. The previously mentioned case of Donna Anthony was overturned in April of 2005. She had served six years in jail for her original conviction.

Dr. Meadow’s fall

Beginning in June of 2005, Dr. Meadow was brought before the British General Medical Council (GMC) for a practice tribunal. The council ruled that Dr. Meadow’s conduct had been “fundamentally unacceptable” and that he was guilty of “serious professional misconduct.”8 On July 15, 2005, Dr. Roy Meadow was struck from the medical register. To the GMC, it was critical the public maintain confidence and trust in expert witnesses, justifying the severity of the penalty. Dr. Meadow left the tribunal without comment.

Despite the ruling, many still defended and supported Dr. Meadow. Professor Sir Alan Craft, president of the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, said the decision to strike off Dr. Meadow was “saddening,” and he stated, “He has had a long and distinguished career in pediatrics in which he has undoubtedly saved the lives of many children. We must be clear however that this hearing focused solely on the evidence he gave in one particular court case. It does not reflect upon the rest of his career.”8

Following the GMC’s decision, Dr. Meadow launched an appeal. In February of 2006, High Court judge Mr. Justice Collins ruled in Dr. Meadow’s favor, overturning the decision to strike him from the medical register. He agreed that Dr. Meadow’s testimonies were to be scrutinized and criticized, but not that his actions were “serious professional misconduct.”

Dr. Meadow is certainly not the first physician in history to raise adverse scrutiny and criticism; and only time will tell whether Dr. Meadow will be remembered for his advocacy for children’s health and well-being or for his role in the jailing of innocent women and the separation of children from their families.

Though MBP is recognized in the DSM-IV, much controversy still underlies its acceptance both in the medical community and society as a whole.

References

- R. Asher, “Münchausen’s Syndrome,” Lancet 1 (1951): 339–341.

- “Baron Münchhausen,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2010.

- R. Meadow, “Munchausen syndrome by proxy—the hinterland of child abuse,” Lancet 2 (1977):343–345.

- “Munchausen Syndrome,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2010.

- T. F. Parnell and D. O. Day, Munchausen By Proxy Syndrome: Misunderstood Child Abuse (London: Sage Publications, 1998).

- BBC News, “Profile: Sir Roy Meadow” (17 February, 2006). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/low/health/4432273.stm. (Accessed 20 February, 2010).

- “Roy Meadow,” State Master Encyclopedia, 2010. http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Roy-Meadow. (Accessed 20 February, 2010).

- BBC News, “Sir Roy Meadow struck off by GMC” (15 July, 2005). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/low/health/4685511.stm. (Accessed 20 February, 2010).

NEREIDA ESPARZA, MD, is finishing her last year of Family Medicine residency at the MacNeal Family Practice Residency Program in Berwyn, Illinois. Originally from Chicago, she hopes to continue to practice in the local area after her graduation.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2013 – Volume 5, Issue 1

Winter 2013 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply