Stefania Spano

Kingston, Ontario, Canada

A history of dark humor

Humor is an ancient tool for subverting tragedy. Parody and satire persuade audiences that even the greatest of grief can be made comical. Art and literature vicariously teach audiences to laugh at their own pains and thus grow beyond them. And what greater pain exists than the knowledge that all earthly life expires?

Humor and celebration are a cross-cultural coping mechanism for the human condition, with many rituals embracing the tragicomedy dichotomy. In ancient Rome, the affluent deceased received elaborate processions: musicians sang funeral dirges for the departed, troupes of comedians and fools entertained mourners, sometimes imitating the departed, and ancestors of the deceased were represented in wax death masks worn by actors.1 Such pageantry was both celebratory and sombre. Similar spectacles occurred in the early nineteenth century in the southern United States. In New Orleans, brass bands followed processions, with slow, melancholy hymns before the funeral and spirited ragtime pieces afterward. Mexico’s annual Día de los Muertos (November 2) is equally joyous, with colorful candy skulls, graveside picnics consisting of the deceased’s favorite meal, and the occasional calaveras, songs and poems with “witty allusions to death or epitaphs.”1 Each ritual acknowledges the memento mori, an artistic concept Latin for “remember that you will die.” Memento mori is a reminder of the eventuality of death and of the tenuous mortality of humanity.

Death in the Dutch Golden Age

The influence of art and culture on the memento mori is also found in didactic depictions of the deceased. In the Baroque period (1600–1750), the role of organized religion in cultural representations of the body greatly influenced representations of anatomy, humanity, and mortality. Under the influence of the Roman church, the body was regarded as the reflected image of a Christian God. In the fourteenth century, the Christian church began sanctioning the dissection of human cadavers, and centers for medical education appeared in Paris and Montpellier in France, and in Salerno and Bologna in Italy.2

The Baroque period also coincided with the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch Republic of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a region of great intellectual growth; of Rationalism and Enlightenment; of anatomy theatres; of openness to innovation; and of minimal censorship. The Dutch Age of Observation also saw refinements in lens optics and advances in astronomy, mathematics, cartography, and physics.3 However, in stark contrast to the religious iconography that had defined Catholic doctrine since the Council of Nicaea, concerns grew amongst Protestants (such as those in the northern Netherlands) about the veracity and didactic value of religious imagery in instructing the “illiterate faithful.”4 Thus, Reformed Protestants turned their focus to the divinity of the individual and of private worship, in turn inspiring a new artistic movement: Dutch genre painting.4

Pieter Claesz

Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis

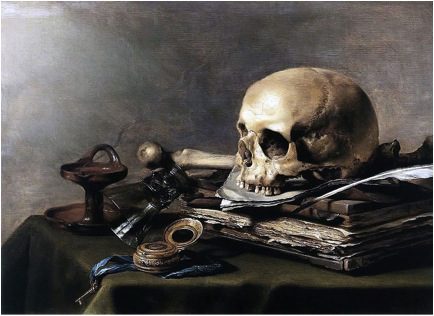

Genre painting depicted the private, modest means of the everyday individual through landscapes, interiors, and portraits, with significant emphasis on depicting the Dutch countryside.5 Furthermore, in response to Catholic imagery, Dutch artists created a subcategory of still life genre paintings known as vanitas art.4 The term vanitas originate from the biblical writings of the Ecclesiastes, “vanity of vanities, all is vanity,” which was then adopted by writers, clergymen, and still-life artists to describe life’s impermanence.5 It was a new, subtler approach of God-through-metaphor, to moral extolling through symbolism and to motifs of the fleeting nature of humanity’s mortal existence.

Vanitas art is rich in allegorical subtext, metaphorical imagery, and ambiguities. Common symbols included fob watches, hourglasses, peacock feathers and pearls, as well as overripe fruit and lemon peels (attractive to see, bitter to taste).5 The most common and stark symbol of the memento mori in vanitas artwork was the “death’s head” itself: a human skull, often juxtaposed with another object of life and youthful splendor. It was the goal of the vanitas artist “to show time’s transformation of the physical world [and] the inevitability of death and humanity’s consequent need for salvation.”3

Ruysch’s remembrance

Jan van Neck

Amsterdam Museum, Holland

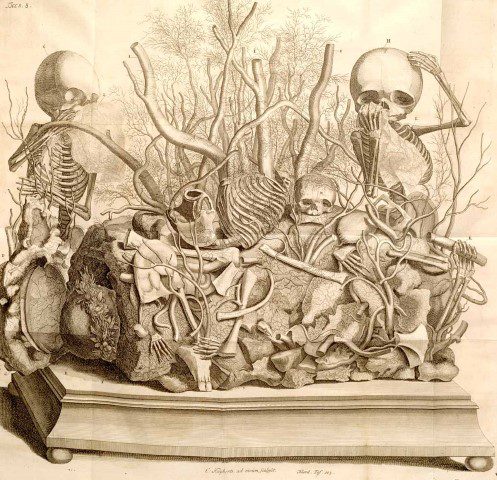

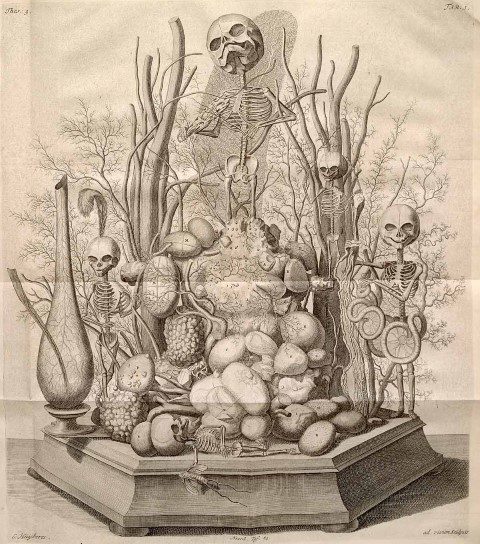

The Dutch Golden Age was in part a response to the new insights provided by discoveries within the natural world, and to new representations of morality through mortality. It is thus unsurprising that the University of Leiden hosted several renowned intellects, including anatomist, obstetrician and surgeon Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731). Unsurpassed in his technique for preparing anatomical specimens, Ruysch is best remembered for his “cabinet of curiosities,” a private anatomical museum that was enthusiastically purchased in 1717 by Russian tsar Peter the Great for his Kunstkammer (“Chamber of Curiosities”).6 One particularly intriguing series in Ruysch’s collection was his tableaux of infant skeletons in still life arrangements. These sculptures represented a unique cross-section of art, society and science. They also exemplified the use of vanitas still life motifs to represent (and later subvert) the memento mori where it is most pervasive: in anatomical artwork depicting deceased subjects. The tableaux proper have long since been destroyed,7 but they are survived by the engravings of artist Cornelius Huyberts in Ruysch’s Thesaurus Anatomicus.

In the first tableau, two infant human skeletons perch atop a pile of bones and lung tissue amidst an arboreal landscape of human and bovine tracheas and bronchi. The two figures are complementary. Ruysch’s notes describe the skeleton on the right as a “Heraclitus” sobbing into his handkerchief (or, rather, into the peritoneal membrane, its vasculature expertly perfused with Ruysch’s secret preservative). “We, robbed of this sweet life and torn from the breast,” Ruysch continues, “are carried off by horrid Death and laid in the dark grave.”7 An additional moment of vanitas is tucked within the mound of tissue: here, a skull wreathed with flowers contrasts spring’s first blossoms and life’s final winter. Yet in a humorous twist, the other skeletal figure to the left, “Democritus,” laughs outright at his companion. This, in turn, succeeds in rendering the Heraclitus figure almost comically melodramatic. Surrounded by bones that match his own, the Democritus figure is “set up in such a way that it seems to be laughing at mankind,” explains Ruysch. This juxtaposition of philosophers recalls the classic tragicomedy symbol: one mask laughing, one mask sobbing, both stripped down to the barest of recognizable human features: the facial bone structure. The tragicomedy masks and Ruysch’s tableau are a reminder of the coexistence and co-dependency of comedy and calamity, life and death, and of humanity’s ability to (literally) laugh in the face of tragedy.

Frederik Ruysch, artist

Cornelius Huyberts, engraver

Detail, Opera Omnia Volume 3

Frederik Ruysch, artist

Cornelius Huyberts, engraver

Detail, Opera Omnia Volume 3

The second of Ruysch’s tableaux has a lively air, considering its subjects. The topmost figure sounds out a silent tune with a bow of dried artery and a violin of osteomyelitic sequester, while the tiny figure to the immediate right conducts with a renal stone-studded baton.7 Along the base, a figure lounges, mayfly dangling from its tiny hand. On the left, a female skeleton poses casually with a large feather emerging from her skull and a pulmonary stone dangling from her hand like a toy bauble. She resembles a child dressed in her mother’s clothing. She stands next to an inflated testicular tunica albuginea, an empty vase that stands as testament to the little deceased girl that will never mature to womanhood. Likewise, a skeleton to the far right is swathed in a delicate pattern of intestine much too large to be his own, and leans on a staff made from hardened adult vas deferens, a tongue-in-cheek implication that “[the skeleton’s] first hour was also its last.”7 The relaxed, almost jovial nature of the tableau contrasts sharply with the vanitas motifs throughout: the vanity of a peacock, the frivolity of exotic items and the uselessness of earthly trinkets; the trivial, transient joy of music; the brief lifespan of a mayfly; twisted intestines snaking about innocent loins. And yet the ambiguity of the piece is part of its success as a work of vanitas still life.

Ruysch’s tableaux reflect the strong contrasts, luxuriant texturing, confident diagonals and ornamental foliage characteristic of such Dutch Baroque Mannerist landscape painters as Roelandt Savery and Gillis van Coninxloo. Despite the fatality of his subjects, Ruysch’s skeletons have an undeniable vitality to them. One observer confessed, “His mummies were a revelation of life, compared with which those of the Egyptians presented by a vision of death. Man seems to continue to live, and to continue to die in the other.”6 And so, in his unabashed depictions of death, Ruysch managed to subvert the mortality of his subjects.

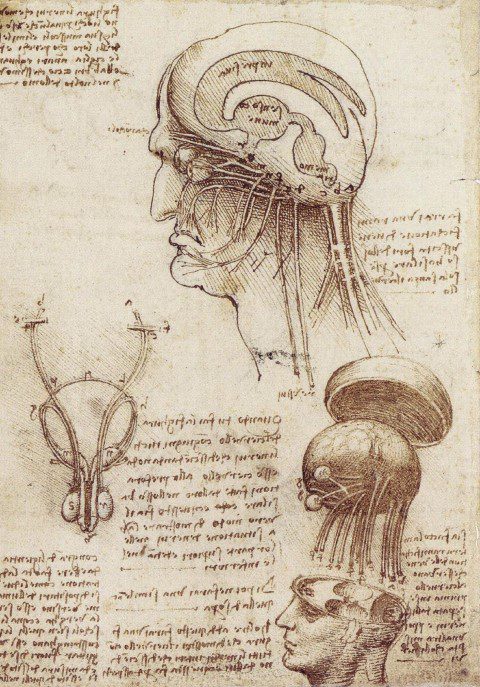

c. 1489 – 1490, Leonardo da Vinci

Death, distanced

Ruysch was not the first to decorate the dead. Mummification is one of the earliest examples of human interference with death and decay. Some of the oldest intentional mummies originate from the Chilean Chinchorro of 7000 years ago.8 Ancestral worship dates back to 8000 BCE, with plaster-covered skulls and seashells for eyes—a precursor to the delicate collars and cuffs made by Rachel Ruysch for her father’s specimens. The cases of Egyptian mummies were painted with magical and religious symbols, hieroglyphs, and images of everyday life1 —an enterprise similar in intention to Dutch genre and still life vanitas paintings.

Unlike Ruysch’s lifetime, when infant mortality was high and life expectancy low (although he died at an impressive 93 years old), contemporary society faces an increasing distance between daily life and the deathbed. The act of dying has been pushed out of homes and into hospitals and long-term care facilities. The vanitas artists did not share this current separation from death acts. Perhaps this is why it may be difficult for modern audiences to perceive Ruysch’s tableaux as graceful rather than grotesque. Perhaps this is why artists of the Dutch Golden Age were so compelled to create vanitas art. For Ruysch, Death was a visitor present both in his everyday life and in the anatomical references he studied. The perceived vulgarity of “graveyard humor,” embodied in pieces like Ruysch’s tableaux, is employed to overpower and thus minimize the perceived vulgarity of the graveyard itself.

As a recurrent coping strategy for the stark, honest portrayal of death, humor is apparent in modern society. Consider Gunther von Hagens, a present-day Ruysch, who pioneered the process of plastination and then used it to preserve human and animal dissections in his BODY WORLDS exhibitions. The exhibitions have been controversial, but again comedy has been used as a vehicle for creating cultural acceptance of an idea. Von Hagens’ tableau entitled Poker Playing Trio (2006) was featured in the 2006 James Bond film, Casino Royale. The tableau shows three male specimens in different states of dissection, all seated around a poker table. The dissections can be jarring for sensitive crowds; one figure sports the “exploded view” of the skull, originally seen in neuroanatomical drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. Yet such tension is immediately relieved when the audience looks below the table: two players are cheating, passing cards between their toes. Of all the BODY WORLDS pieces, the one that would act as von Hagens’ Hollywood ambassador came with a punch line.

Conclusion

Is it vulgar to put the bodies of the deceased on display in a theatrical manner? Does humor belong in the world of anatomical art? Regarding medical museums, Christine Quigley suggests, “If the specimens [. . .] are displayed with respect and the questions are answered truthfully and scientifically, the exhibit has social and scientific legitimacy.”9 Ruysch’s artistry was matched by his commitment to the underlying science and to using the materials of the dead to teach the living. “I do this,” he explained, “to take away from these people all repulsion, the natural reaction of people confronted with corpses being one of fright.” In exploring different historical perspectives and cultural practices towards art, death, and the body, it becomes clear that humor and jocundity are recurrent responses to the laments of the human condition. The prospect of mortality can create a paralyzing fear, especially when so starkly experienced in life or, ironically, immortalized in art. In medical art and in mourning rites, humor simply helps the living to see the dead, to witness their mortality in the passing of others, to accept it, and to see the life beyond it.

Acknowledgements

Department of Biomedical Communications, University of Toronto

Dr. Jacalyn Duffin, Hannah Chair, History of Medicine, Queen’s University

References

- Colman, P. Corpses, Coffins, and Crypt: A History of Burial. 1st ed. New York, NY: Henry Holt; 1997.

- Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. Richard Landon, Philip Oldfield, and Associated Medical Services Inc. Ars Medica: Medical Illustration Through the Ages: An Exhibition to Commemorate the Seventieth Anniversary of the Founding of Associated Medical Services: Exhibition and Catalogue. Toronto: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library; 2006.

- Kuretsky, S. D. Time and transformation in seventeenth-century Dutch art. Poughkeepsie, NY: Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College; 2005.Fernández-Armesto F, Wilson DA. Reformations: a radical interpretation of Christianity and the world, 1500-2000. New York, NY: Scribner; 1997.

- Rosenberg, J., Slive, S. and ter Kuile, E. H. Dutch Art and Architecture, 1600-1800, The Pelican History of Art Z27. Harmondsworth, Middx: Penguin; 1966.

- Brier, B. The Encyclopedia of Mummies. New York, NY: Facts on File; 1998.

- Luyendijk-Elshout, A. M. Death enlightened: A study of Frederik Ruysch. JAMA. 1970;212 (1):121-126.

- Sloan, C., and National Geographic Society (U.S.). Bury the Dead: Tombs, Corpses, Mummies, Skeletons & Rituals. Washington, DC: National Geographic; 2002.

- Quigley, C. Modern Mummies: The Preservation of the Human Body in the Twentieth Century. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.; 1998.

STEFANIA SPANO, MScBMC, originally from Thornhill, Ontario, is a biomedical artist and second-year medical student from Queen’s University (Kingston). A two-time alumnus of the University of Toronto, Stefania holds an Honours Bachelor of Science in Neuroscience and English, as well as a Master of Science in Biomedical Communications. She has a special interest in reconstructive plastic surgery, global surgery initiatives, data visualization, and knowledge transfer among health care professionals. Outside of medicine, Stefania enjoys the arts, 19th century British literature, creative writing, and owning several shelves of half-read books. She is thrilled to be participating in the Hektoen Essay Contest.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 6, Issue 3 – Summer 2014

Leave a Reply