Alexandra Mavrodi

George K. Paraskevas

Thessaloniki, Greece

No other field of medicine is as strongly attached to art as anatomy. Because it relies so heavily on using images, anatomy has always greatly depended on the participation of the artists. Its anatomical atlases, influenced especially during the Renaissance by the prevailing fashions in art, were created not only for teaching purposes but also to serve the needs of artists, painters, and sculptors, who used anatomical figures as patterns to create lifelike human figures.

One such example of an anatomical atlas used by artists was Bernardino Genga’s “Anatomia per uso et intelligenza del disegno,” meaning “Anatomy for the proper use and understanding of the design.” Created by the artist Charles Errard (1606-1689), it was based on the anatomical preparations of Bernardino Genga. Errard, court painter to Louis XIV, was the first director of the Academie de France in Rome.1 Genga (1620-1690), born in Mondolfo on the Duchy of Urbino, practiced surgery in the Hospital of Santo Spirito in Sansia and studied thoroughly the classical medical texts. His great interest in connecting anatomy to art (as shown by several anatomical images of his collections inspired by classical sculpture and more precisely by statues like Laocoön and Farnese Hercules) led him to the Academie de France in Rome, where he taught anatomy to artists.2

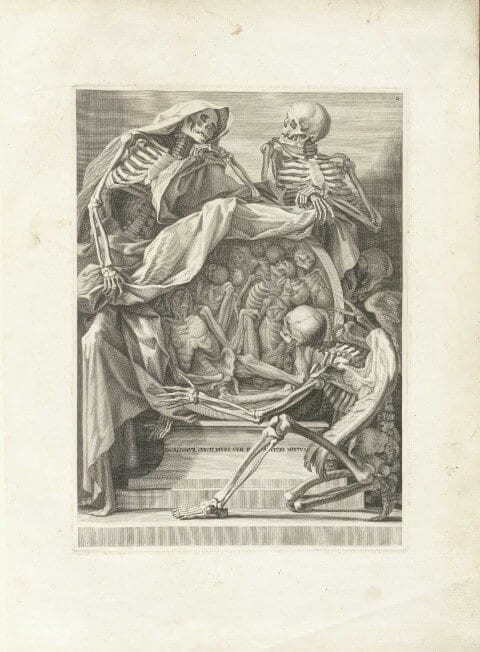

The most well-known of Genga’s drawings is his “Anatomia’s” frontispiece (Fig. 1), which irrefutably constitutes a real piece of artwork drawn by Errard. The center of the image is occupied by a large sphere resembling a heavenly body. In its inside, which is exposed to view, one may distinguish a heap of human bodies perhaps in the last moments of their lives. Some are skeletons, others so scrawny and dried that their bones can be seen under their skin in great detail. They are all in different stages of decomposition and seem to accept with resignation and even stoicism their common fate, death, which mangles not only their body but also their soul. Every tiny part of their body seems to be suffering, and the way they are thrown over one another reveals their abjection, loss of identity and human dignity as a result of the invasion of death. The sphere in which all of them seem to be trapped as though buried in a mass grave is reminiscent of the earth which “eats” the dead. This sphere is surrounded by three skeletons, whose larger size compared to the human bodies imply that they have some kind of power and authority over the humans. The first two abut against the dome of the sphere, one on the left and one on the right. The one on the left wears a cloak, which also conceals part of the sphere. The two skeletons hold the cloak in their hands so as to unveil the inside of the sphere. Though looking like collaborators as they seem to imperturbably discuss the end of the human souls in the sphere, the cloak presumably gives the skeleton wearing it domination and supremacy over the other two. Hypothetically, the mantled skeleton might be the personification of Death, while the third skeleton could be his messenger. This last skeleton kneels down in front of the sphere as he gazes at the human figures and stretches his left hand ready to pick one of them. He is distinct from the others because of the wings coming off his scapulae. This angel-skeleton seems to be an angel of evil, which renders him even more dreadful.

The painting as a whole gives a sense of a three-dimensional statue. Although its protagonists are skeletons, their poses and the expressiveness of their bodies add an ancient Greek style to the composition. The date of its creation, however, places the work in the baroque period. Cultivated in Rome when Genga was active, baroque as an artistic style was characterized by clarity, extreme detail, and exaggeration, often covering topics of morality, religion, and the continual conflict of life and death. All these characteristics are present in the frontispiece of Bernardino Genga’s “Anatomia.” Remarkable is the slightly illegible inscription at the base of the sphere referring to the common fate of the rich and of the poor. The image, though created for an atlas of anatomy, has an emotional and artistic background that qualify it as a true work of art.

References

- Michael Sappol, Dream Anatomy (Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, 2007), 135.

- “Historical Anatomies on the Web”, last modified June 5, 2012, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/genga_bio.html

ALEXANDRA MAVRODI is currently a 5th year undergraduate student at School of Dentistry of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. She is assistant at the Department of Anatomy at Faculty of Medicine of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Additionally, she is interested in the history of anatomy. She is co-author of several articles (“The history and the art of anatomy: a source of inspiration even nowadays” published by Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology, “Mondino de Luzzi: a luminous figure in the darkness of the Middle Age” published by Croatian Medical Journal, “Evolution of the paranasal sinuses’ anatomy through the ages” published by Anatomy and Cell Biology, “Morphology of the heart associated with its function as conceived by ancient Greeks” published by International Journal of Cardiology, “Unusual Morphological Pattern and Distribution of the Ansa Cervicalis: a case report” accepted in Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology).

GEORGE K. PARASKEVAS, MD, completed his medical degree in 1994 at Faculty of Medicine of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece and gained full qualification as Specialist in Orthopedic Surgery in 2005 (Thessaloniki, Greece). He obtained his doctoral degree (Dissertation) in 2000 at the University of Thessaloniki. Currently he is Assistant Professor at the Department of Anatomy at the Faculty of Medicine of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, since 2009. His research interests and specialties include surgical anatomy and embryology of gastrointestinal tract, surgical anatomy and congenital anomalies of bones, joints and muscles, entrapment syndromes of nerves and neuropathies, variational anatomy of vascular system, trauma, and surgery. Dr. Paraskevas is a member of various medical societies and of editorial board of 28 international peer-reviewed journals. He is also author and co-author of 10 textbooks and has published more than 120 papers on peer-reviewed journals indexed in PubMed.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 8, Issue 1 – Winter 2016

Leave a Reply