James Mackenzie was a prominent and highly influential British physician who made great contributions to the understanding of cardiac diseases, especially of atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias. He was “at heart” a generalist, having spent 28 years as a general practitioner and after a decade in London returning to his roots in Scotland to study the early causes of disease. Indeed he did not like being called a heart specialist, and certainly not a cardiologist. Accordingly his memory continues to be held in high esteem not only among cardiologists but also among general practitioners or primary care physicians associations.

Born in 1853 in Scone, Perthshire, Scotland, he was educated first in the village school and later at the Perth Academy. At age 15 he left school for a pharmacy apprenticeship, qualifying as a pharmacist at the age of 20, but then enrolling in the faculty of medicine at the University of Edinburgh. On graduating in 1879 he entered private practice in Burnley, Lancashire, taking residence in the house of the senior partner of the firm. Described as “a gaunt, gauche, determined, ambitious youth,” he worked many hours every day, taking clinics and doing house calls, but reserving one afternoon a week to play golf.

Burnley (21 miles north of Manchester and once a successful football team but now languishing in a lower division), had at that time a population of 100,000 people. Transformed by the Industrial Revolution from a 5,000 inhabitant sheep farm and weavers village, it was a grim industrial town of factories, warehouses, foundries, and coal mines, with appalling housing conditions, bad sanitation, and a large population of indigents and even vagrants. In that town Mackenzie practiced for over a quarter of a century, becoming what in later publications had him described as the “Beloved Physician.” Patients recall his clinic, with its wooden seats where “men and women, often shalled or muffled and clogged,” would patiently wait on wooden seats to collected their bottle of medicine from the adjacent dispensary. By 1886 a medical hospital had been built and was opened; but most of the care was rendered in the home, the doctor calling with his bag of instruments and remedies, including, it appears, a small set of instruments that he later described as being very useful for doing postmortem examinations in people’s homes.

Mackenzie had (and thought doctors should have) a great deal of curiosity and carried out clinical research sparked of caring for patients. His interest in cardiac disease was kindled by one of his patients with mitral stenosis unexpectedly dying in childbirth. He read widely about heart disease and began studies of arterial and venous pulses, for which he invented the “Mackenzie polygraph” a machine based on the sphgmograph. With this device he could take tracings of the radial, jugular, and hepatic pulses. At first his clinical observations were not appreciated by the medical establishment, his lectures met with blank stares and no questions asked at their end, but gradually his reputation grew, especially abroad. By 1905 he was receiving in Burnley many visitors, by Osler from Oxford and Wenckebach from Germany.

In 1907 Mackenzie moved to London to set up a consultant practice, in part, it seems, in the hope of finding young men who would use the new techniques he had described. In 1908 he published a book, Diseases of the Heart. In this he affirmed that many cardiac murmurs were benign, as were sinus arrhythmia and most extrasystoles, not requiring long periods of confining to bed as was occasionally the practice. Based on his careful studies of the venous pulse, the observed the absence of the A wave in irregular hearts, first attributing it to paralysis of the atria but then accepting his assistant Thomas Lewis’s interpretation that the atria were fibrillating. Knighted in 1915, he established the first cardiac unit at the London Hospital, and inspired a group of talented assistants, including Thomas Lewis and John Parkinson (both later knighted), thus laying the foundations for an eminent British school of cardiologists.

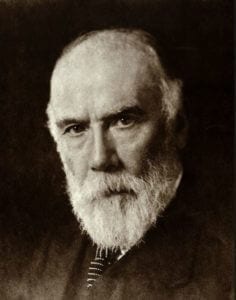

Tall, massively built, bearded, “a big brown bear,” he spoke in a Scotts accent, did not suffer fools gladly, was sometimes dogmatic but courteous and polite. Emphasizing bedside inspection and auscultation of the heart and careful examination of the neck veins, he was conservative in the use of drugs. It is reported that he wanted to observe the patients in the hospital for one week before starting medications, something clearly not feasible nowadays (!). He favored using one drug at a time to observe its effects, and disliked drug combinations. In 1917, satisfied that his work on the heart had now been accepted and not interested in maintaining a fashionable practice in London, he left for St. Andrews. There he established an institute to study the early causes of disease, anticipating the Framingham study by almost half a century.

In 1908 the doctor himself developed the disease he had been studying and treating. It began with a two-hour episode of atrial fibrillation and chest pain that may have been his first myocardial infraction. Over the years this was followed by angina attacks of increasing severity, on exertion or at rest, and gradual reduction of exercise tolerance. He died in 1925 following several attacks of severe pain. Postmortem examination of the heart, carried out at his express request by Sir John Patterson, showed areas of infarction, much coronary artery arteriosclerosis, calcification, and narrowing or occlusion. The changes seemed more severe in the right coronary artery. Modern arterioplasty techniques would no doubt have rendered him pain-free in his 17 years of angina. Perhaps he might even have lived longer.

References

- Parkinson J. Sir James Mackenzie. The centenary of his birth. British Heart Journal. 1954; 16:125

- Lord Amulree. Sir James Mackenzie. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1962; 87:551

- Wales AE and Shafar J. Sir James Mackenzie: The Burnley years. Medical History. 1967; 11:297

- Horder JP. The opinions of Sir James Mackenzie. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1972; 22:799

- Southern, M. Sir James Mackenzie. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1973; 23:755

- Hollman A. How John Parkinson did the postmortem on Sir James Mackenzie. British Heart Journal. 1993; 70:587

- Watterson D. Sir James Mackenzie’s heart. British Heart Journal. 1939; 1:237

Leave a Reply