Rebekah Abramovich

New York, United States

|

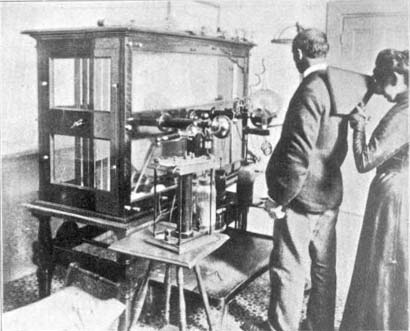

| Fig 1. Fleischmann Examining a patient with a fluoroscope (Camera Craft, June 1901). Courtesy of Palmquist |

Elizabeth Fleischmann-Aschheim (1865–1905) opened California’s first X-ray photography laboratory in 1896, merely one year after Roentgen’s discovery. Over the course of the next decade, this unlikely figure would become one of the most respected radiographers of those pioneering years.

She was born in 1865 in El Dorado County, California, one of five children of a Jewish couple originally from Austria, Jacob and Kate Fleischmann. Jacob worked as a baker and because of economic hardship moved his family in 1880 from the Placerville area to San Francisco. By 1882 Elizabeth had quit her senior high school year in order to help her family. Little is known about her between the ages of 17 and 29. Still single at age 29, she continued to live with her family and work as a bookkeeper for a Bay Area underwear manufacturer, Friedlander & Mitau.

Roentgen announced his X-ray discovery in 1895, but the news of the technology did not reach the English-language press until January 1896. At the time Fleischmann’s brother-in-law was a physician who ran his practice out of the family house. This close proximity to a member of the medical community no doubt alerted Fleischmann early to the trend. Astoundingly, by mid-1896 she had already set up and equipped her own x-ray photography laboratory at 611 Sutter Street, San Francisco, the first of its kind in California.

During the Spanish-American War, many wounded Army troops returned from the Philippines through San Francisco. Fleischmann was known to be able to locate bullets and splinters of shrapnel better than any other technician in the area. Word of Fleischmann’s superb abilities quickly spread. The Surgeon-General of the Army visited Fleischmann’s studio himself and became a vocal fan.

An article about Fleischmann’s adept skill as a technician of these revealing rays appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1900. It describes the contemporaneous understanding of radiography and its practitioners clearly:

|

| Fig 2. Belgian Hare (Camera Craft, June 1901) Courtesy of Palmquist |

The object is placed upon the sensitive plate which is to be the negative, and the rays of the Crookes tube are directed downward upon and through it for a brief time, penetrating all woven fabrics as if they were mere vapor, piercing the flesh which appears in the radiograph as a faint film, passing through cords and muscles and bones with varying facility, the result showing the exact degree of resistance offered by all these substances; when the rays find a metallic substance, offering an absolute barrier to their progress, they leave the latter as a black shape on the radio-graph. The principle is as simple and elemental as the shadows thrown upon the ground by sunlight or electric lights, but the radiograph which shall serve the delicate uses of surgery and be an infallible guide for an operation on which hang life and death, requires a consummate skill, experience, and a fineness of judgment and perception which is almost like a sixth sense.

In addition to making strides in medicine, Fleischmann instantly began to explore the medium’s artistic potential. She delved into the invisible structures of common objects, from the previously hidden interior of a shoe to the rounded skeleton of a cat. Camera Craft, a popular photography journal, published several of Fleischmann’s radiographs in 1901, transporting the images from the realm of science to art.

An article on Fleischmann in The San Francisco Chronicle demonstrates the early view that x-rays might aspire to art. The early speculators understand its potential to visually reveal and transform:

Radiography is varied in its applications, having its light as well as its serious side. It reveals the bony structure of living animals with remarkable fidelity. The gauzy anatomy of the frog, the delicate articulation of the snake, become things of beauty beneath its power.

Sadly, like the early practitioners of radiography who were lost too soon, all x-rays created by Fleischmann disappeared, and there are no known examples left today. Fortunately, the San Francisco Chronicle and Camera Work published several of her radiographs, so that a tangible document of her work survives.

One must step back for a moment to consider the many ways in which Fleischmann’s path and achievements were unconventional for her time. She was a single Jewish woman of thirty years old when she learned the trade and opened her laboratory. It was not common at the time for a woman to go into a commercial enterprise on her own in San Francisco. Also, Elizabeth waited until her mid-thirties to marry, eventually committing herself to Israel Julius Aschheim. It is worth noting that on marrying Fleischmann hyphenated her name, another surprisingly modern move.

She was also unique in her chosen profession because she was a high school dropout working in the realm of medicine. She always created her x-rays in conjunction with a doctor as the diagnostician, but Elizabeth’s equipment and techniques were cutting edge. Photographic historian Peter Palmquist notes that Fleischmann’s laboratory is the only one listed in the 1896 San Francisco directory, and that radiology laboratories outside of hospitals do not otherwise appear until 1917, over a decade later.

The earliest practitioners of radiography had no idea what the health implications could be from constant exposure to radiation. In these early x-rays, subjects were often exposed to massive doses of radiation, exposures between twenty minutes and several hours. Radiographers often placed their hands in front of the fluoroscope to check exposures, and x-ray tubes were not shielded. Radiation burns were immediate; radiation poisoning was cumulative.

In 1904 Fleischmann-Aschheim’s arm had to be amputated because of damage from radiation. By the next year, less than a decade after mastering her trade, Elizabeth Fleischmann-Aschheim was dead. It was a death full of suffering, and her obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle read, “Death came as a relief.” Throughout, she maintained her laboratory and practice. Her tombstone in Salem Cemetery, outside San Francisco, is inscribed: “I think I did some good in this world.”

References

- Anon. “Death of a Famous Woman Radiographer [obituary notice],” San Francisco Chronicle, August 5, 1905: 10.

- Anon. “The Woman Who Takes the Best Radiographs,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 3, 1900.

- Anon. “Marvelous Electro Machine,” San Francisco Call, February 7, 1897: 11.

- Brown, Mary. “X-ray Photographer: Elizabeth Fleischmann,” Found SF Blog, January 8, 2009. http://foundsf.org/index.php?title=X-ray_Photographer:_Elizabeth_Fleischmann.

- Kyta, Theodore. “Radiography,” Camera Craft, illustrated by Elizabeth Fleischman-Aichheim, June 1901: 51-7.

- Palmquist, Peter E. Elizabeth Fleischmann: Pioneer X-Ray Photographer (exhibition catalog). Berkeley, California: Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1990.

- Rochlin, Harriet. “Woman, Jew, and Westerner: Excepts from ‘A Mixed Chorus,’” Harriet Rochlin & Western Jewish History. http://rochlin-roots-west.com.

REBEKAH BURGESS ABRAMOVICH, PhD, works as the Archivist for the LIFE Magazine Photography Collection, managing 23 million images taken on assignment for LIFE Magazine (1936–1972). She previously worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Abramovich received her PhD in American Studies focusing on Photographic History from Boston University in 2008.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2015 – Volume 7, Issue 1

Winter 2015 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply