James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

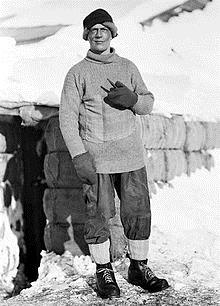

Edward Leicester Atkinson (1881–1929)—known to the members of the Terra Nova Expedition as “Atch”—was senior expedition surgeon of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910-1913. Born in the West Indies to European parents, he studied medicine at St. Thomas Hospital in London. Shortly after joining the Royal Navy, he applied for a place on Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic Expedition. Both he and Edward Adrian Wilson had studied with the eminent parasitologist Robert Leiper of the London School of Tropical Medicine. Atkinson was appointed to serve as both a physician and research parasitologist on the Terra Nova Expedition. He was a short stocky man, powerfully built, and in 1905 had won the lightweight boxing championship of the United Hospitals. Atkinson made several sledging journeys during the Terra Nova Expedition under perilous conditions; there is no doubt that his physical training as an amateur prizefighter aided him in accomplishing these feats.

For the members of the Terra Nova Expedition the early months of 1912 were grim indeed. By March 1912, Scott’s polar party (last seen on December 21, 1911) was clearly overdue and there was a mounting fear that they had perished. In addition, a party of six men under the command of Lieutenant Victor Campbell was stranded on the other side of McMurdo Sound. This left Atkinson as senior naval officer in command of thirteen men facing four months during which the sun would not reappear. In March he made a six-day journey in a futile effort to locate Scott and in April he took five men in an attempt to rescue Campbell’s party. It was unsuccessful and perhaps foolhardy to venture out on the treacherous ice of the Ross Sea. As one of his companions noted: “Atch altered tremendously in the second year from the carefree naval surgeon of the first year . . . I think we all grew to have great respect and affection for him . . . there was not the least discord that winter.” In late October, with the sun just starting to reappear over the horizon, he led the search that discovered the missing polar party. On November 12, they found Scott’s tent partially buried in snow. Atkinson was the first to enter and view the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers and to read the records of their final days.

On January 17, 1913 the Terra Nova returned to Cape Evans to pick up Scott and the members of the expedition with the expectation of a celebration. However, it was not to be and the celebratory bunting was quickly removed. With flags lowered to half-mast, the Terra Nova returned to New Zealand with the remaining members of the expedition. It was on February 10th that the world learned the fate of the polar party. Mrs. Scott and Mrs. Wilson had traveled to New Zealand to greet their husbands and the Terra Nova only to learn that they had been dead for almost a year. Atkinson had the grim task of handing over their husbands’ diaries plus their letters of farewell and escorting the two widows back to England

Atkinson was thirty-one when he returned to England. He completed his parasitology studies from the expedition and published them in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society. He had discovered many new helminths and named them in honor of members of the expedition.

Following his return, Atkinson was the stationed in China to investigate the life cycle of the trematodes infecting men of the Navy on the Yangtze River and causing schistosomiasis. By August 1914 he was working in Japan when he learned of the war erupting in Europe. He immediately departed for England, arriving that same month, and was assigned to the HMS St. Vincent.

Atkinson married Jessie Ferguson of Scotland just before joining the Allied Campaign in Gallipoli in the summer of 1915. Landing at Cape Hellas he faced a major outbreak of dysentery and typhoid. Sanitation was abominable and Atkinson’s major efforts were aimed at improving sanitation and killing the swarms of flies that were spreading disease. A classified disinfectant, Liquid C, was a major subject of investigation and its use met with some success. The Allied withdrawal from Gallipoli at the end of 1915 coincided with Atkinson’s own evacuation as he was suffering from typhus, pleurisy, and pneumonia.

Once back in England, Atkinson arranged to be posted in France with a howitzer brigade of the Royal Marine Artillery. He sustained shrapnel wounds to his face and eyes, but two weeks following surgical extraction he was back on duty as a field doctor. He sustained a second wound and by October 1915 and was evacuated to naval duty in England. His wounds required further surgery and he received the Distinguished Service Order for his heroism at the front.

The closest he came to returning to Antarctica was in May 1916 when he was asked to lead a rescue party to locate Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and the Endurance that had not been heard from since leaving South Georgia in December 1914. Atkinson preferred to serve the war effort, but he reluctantly agreed to search for Shackleton. When news broke that Shackelton had returned to South Georgia, Atkinson was able to remain in France.

In August 1918 he was appointed to the HMS Glatton, a ship laden with ammunition. An explosion and fire occurred while the ship was still in dock. Atkinson made three attempts to go below deck and twice rescued men who had lost consciousness. On the third attempt there was another explosion in which he was knocked unconscious, badly burned, and blinded. One eye had to be later removed, but he lived to receive the Albert Medal for gallantry.

After the war Atkinson served in the navy for another decade, but the accumulated trauma from his multiple injuries eventually led to his discharge. In July 1928 his wife died after a long battle with cancer (one wonders how much of their married life was spent together). He remarried in that same year and sailed for India as a doctor on a civilian ship. Death came some three months later from heart failure.

Today his name only surfaces in the many books documenting the Terra Nova Expedition and the story of Scott and Roald Amundsen’s race to the Pole. In his excellent article on Atkinson published in the Journal of the History of Medicine and the Allied Sciences in 1991, William C. Campbell noted: “Atkinson made a modest but lasting contribution to the science of parasitology, he was a dedicated and caring physician and a natural leader and heroic adventurer.”

References

- Campbell, William C. “Edward Leicester Atkinson: Physician, Parisitologist and Adventurer.” The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1991;46:219-240.

- Campbell, William C. “Presidential Address: Heather and Ice: An Excursion in Historical Parasitology.” Journal of Parasitology 1988;74(1):1-12.

- Huntford, Roland. The Last Place on Earth. New York: Atheneum, 1983. Surgeon. Scotland, UK: Whittles Publishing Ltd., 2011, p. 181.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Leave a Reply