Barbara Majdowska

Dublin, Ireland

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” claimed philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. But for aphasia patients, this is a problematic and frustrating statement. Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a neurological disorder characterized by advancing loss of language function. However, in contrast to other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, PPA language deficits develop separately from other symptoms. Typically in PPA, other brain functions remain intact for two or more years after language starts to decay.1 In the initial stages, people with PPA have fully intact cognition and memory; however, they lack the ability to express themselves verbally. This understandably leads to frustration, as a primary form of interpersonal communication—language—is lost.

However, language is not the only means of self-expression; art can serve as a substitute. Some would argue that the artistic abilities of people with PPA could be enhanced by the neurological changes caused by the disease.2 According to Seeley, people in the early stages of PPA may exhibit an extraordinary and rapid development of artistic abilities. Anne Theresa Adams was someone who developed new visual creativity as a person later diagnosed with PPA. Her story has resulted in new insights into the development of artistic drive in the context of this progressive illness.

Adams was a scientist, but she left academia when her son was injured in an accident. Around that time, she began painting and later left her scientific career for good. At first, her paintings were quite conventional. But as her artistic abilities bloomed, she began to translate music into visual art, creating so-called transmodal art. When she became intrigued by Maurice Ravel’s Boléro, she decided to represent this piece visually. Interestingly, Ravel also suffered from a form of degenerative dementia that affected the language network.3 Ravel composed Boléro and Adams created Unravelling Boléro at a similar age, during the pre-clinical phase of their conditions.

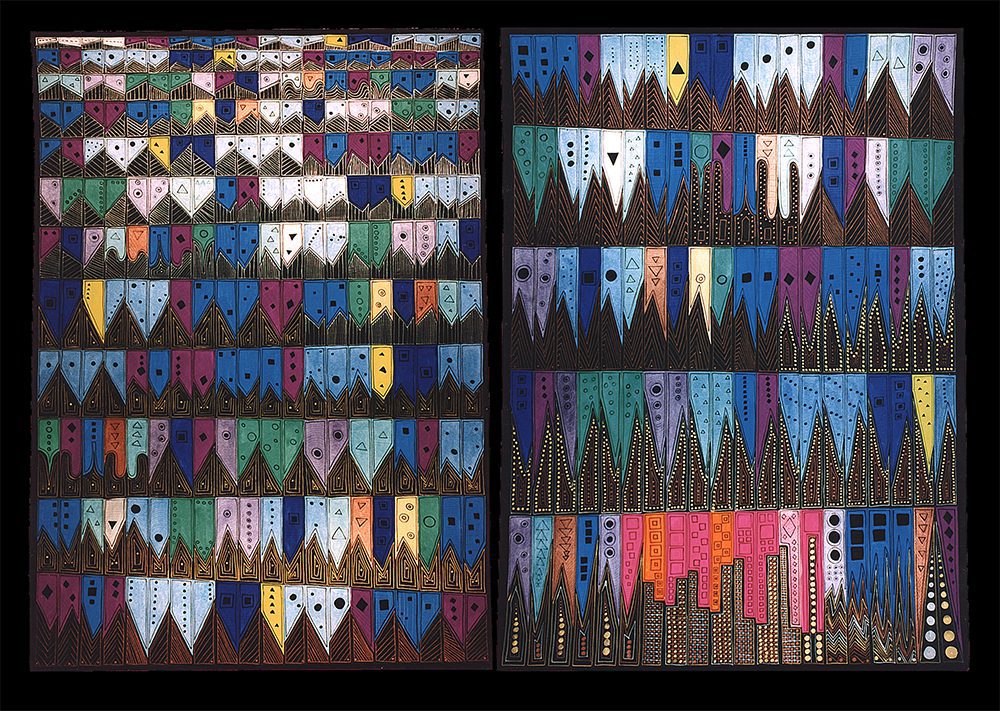

Boléro is a unique and popular work of classical music. Ravel himself described it as “an orchestral fabric without music.”3 The piece consists of two melodic themes repeated eight times, alternating in volume and tone. It stands out from Ravel’s other compositions, giving support to the idea that the developing illness could have influenced the work.3 In her neatly-titled painting Unravelling Boléro (Figure 1), Adams represents each bar of music with a separate rectangle arranged in a zig-zag pattern, using various transformations to visualize different musical characteristics. Lengths of the rectangles are representative of the intensity of the bars, while shapes are used to picture music quality and tone. Almost the whole painting is done in a rather dull color palette, up to bar #326, where bright colors like orange and pink are introduced to emphasize the music’s culmination. Both the music composition and the painting were constructed with great attention to detail, with magnificent yet unconventional results.

Adams’ later work became more and more abstract and frequently showed signs of repetition (Figure 2).2 When her verbal skills declined, she started to communicate with her husband using drawings as well. Towards the end of her artistic journey, photorealistic pieces (Figure 3) dominated her works, pointing towards the possibility that in the end-stage of the disease, visual stimuli may have dominated her inner landscape, as she was no longer capable of verbal language expression.2 Adams put her brush down only after her motor skills were impaired, but painted well past the time she stopped speaking and even understanding speech.

Even though artistic abilities are highly prized, the brain mechanisms responsible for the creation of art remain a mystery. Much of our understanding about the mind’s functioning is based on observations of people with damage in various regions of the brain.2 Beginning when the first symptoms of PPA appeared, Adams underwent a series of brain scans, and her brain function was regularly monitored. PPA is associated with degeneration of the gyri in the left hemisphere, impacting the frontal, temporal, insular, and parietal areas. These are vital brain regions for language processing.1 Such changes were observed on Adams’ scans, but they also showed an increase in gray matter and blood flow in the right (non-dominant) posterior neocortex.2 This part of the brain is associated with multi-sensory processing. It has been suggested that atrophy of the dominant inferior frontal cortex might disinhibit the non-dominant posterior part of the brain and allow this region to undergo structural and functional changes, creating an opportunity for new, rapid artistic development.2

As people with early PPA become unable to communicate with words, art might be of special importance to them. Some exhibit a special interest in structured, detailed, and symmetrical art.2 Perhaps art could relieve frustration and provide an alternative means of communication and expression. Further scientific investigation into artistic development in people with cortical deficits will in turn allow us to better grasp the processes behind artistic endeavors, shining another light on the significance of art in individual lives and human culture.

References

- Johnson N. “A review on primary progressive aphasia.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2008;3:745-52. doi:10.2147/ndt.s1493

- Seeley WW, Matthews BR, Crawford RK, et al. “Unravelling Bolero: progressive aphasia, transmodal creativity and the right posterior neocortex.” Brain Jan 2008;131(Pt 1):39-49. doi:10.1093/brain/awm270

- Amaducci L, Grassi E, Boller F. “Maurice Ravel and right‐hemisphere musical creativity: influence of disease on his last musical works?” European Journal of Neurology. 2002;9(1):75-82. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00351.x

BARBARA MAJDOWSKA is a second-year medical student at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. She was born and raised in Poland, however, she moved to Dublin to pursue her university degree. She has always been interested in various forms of art and is now looking forward to exploring their connections with medicine.

Leave a Reply