Sayantu Basu

Kolkata, West Bengal, India

|

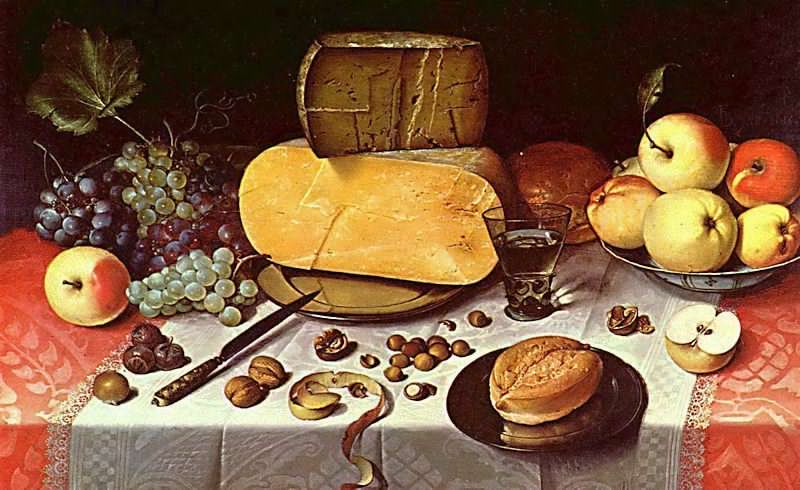

| The Colors of Feast: Still Life with Fruits, Nuts and Cheese Floris van Dijck, Frans Hals Museum, Harleem, Netherlands |

“Nothing would be more tiresome than eating and drinking if God had not made them a pleasure as well as a necessity.”

This is how Voltaire upholds the significance of food in human existence and in a way summarizes man’s dependence on his daily source of energy. Food has always played a valuable role in social and cultural lifestyles. Choice of food, eating patterns and rituals, preference of dining acquaintance, and the motives behind them are instrumental to understanding human society.

Food has found its due place and importance in human creativity and has been expressed recursively in art and literature. Appearing in multifarious contexts, this practice stretches back to ancient Greece and Rome, where banquets and bacchanals were celebrated in literature, paintings, and mosaics.

In the fifteen century, artists, inspired by the culture of antiquity and the natural world, began depicting a variety of still life objects with food their primary source of inspiration. By the seventeenth century, the art world became fascinated with the exquisite realism and detail of food in still life and it soon became a genre of its own.

The Dutch and Flemish masters depicted abundant and lavish food items such as game, fowl, lobster, shellfish, and exotic citrus fruit. These expensive delicacies were associated with a privileged lifestyle that the owner of the painting wanted to be identified with. Vermeer, on the other hand, took a different route than his Dutch contemporaries. In his famous painting The Milkmaid, he used expensive pigments, rich colors, and exceptional lighting to paint the most common of foods—milk and bread. The symbolic potency of this kind of imagery lived on into the eighteenth century.

By the end of the nineteenth century, artists started painting moments from real life. They depicted people socializing around food, or peasants and farmers eating their simple meals, as in Vincent Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885). Impressionists depicted harmonious scenes of collective dinners revealing the social aspect of food, such as Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass or Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party.

The twentieth century witnessed the arrival of cubism and abstract expressionism. Artists deformed lines, juxtaposed planes, removed depth of field, reinvented color and amidst all this, food lost its shape and flavor. Food also became an excellent subject matter to comment on the changing nature of society. Edward Hopper’s Tables for Girls (1930) shows two patrons eating out, something not everybody could afford at the time, and a cashier and a waitress, both women, in new roles outside the home. Food now often carried a symbolic meaning or an allusion to a deeper thought or issue.

With economic development and the arrival of consumerism in the mid-twentieth century, pop artists began to introduce everyday objects into high art. Paintings now showed the dullness of mass-produced food and often questioned the consumer ideal. Warhol criticized the rise of a homogeneous society through his work 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Lichtenstein’s Still Life with Crystal Bowl (1973) appeared surreal, as if the fruits in the bowl were cut off a magazine or a comic book, fake and unsubstantial.

In the 1960s, with the emergence of the new movement called Eat Art, food came out of the canvas and became a material just like paint, pencil, or paper. The food was used in a variety of ways to create ephemeral art. Jan Sterbak created a dress out of sixty pounds of raw flank steak titled Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic in order to make a visual statement about food and humanity. The Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija used food in a more performative sense. In the 1990s, he organized staged happenings where he would cook Thai food and feed everybody who came to the gallery. In this way, the food became a medium for social interaction, and attendees eating and socializing became active participants in the artwork.

The ability of food to create cross-cultural dialog or to serve as a tool for social commentary remains prevalent in contemporary art as well. Food imagery is recreated over and over again in countless compositional interpretations, as well as in literary works. A common setting related to food in children’s literature is teatime. Usually employed to dramatize states of harmony or disharmony, teatime is used to great effect in works like Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1866). Dinner scenes in J.K.Rowling’s Harry Potter series have played crucial roles in setting the ambience of its world of magic. Food images are also used liberally in such tales as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1961).

In addition to reflecting social order and civilization, food is often representative of the limitations imposed on a child’s world, blending well with the idea of excess as a key element of childhood fantasy. For example, Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen (1963) uses food as a vehicle to express strong childhood emotions, and, like many other children’s texts, uses rituals of eating as a metaphor for the power struggle inherent in family dynamics.

Food also offers a means for powerful imagery in adult literature. Visual images in the works of authors such as Katherine Anne Porter and Margaret Atwood are often used to increase the realism in their writing. Details about food in such collections as Porter’s Flowering Judas and Other Stories (1935) create a powerful sense of richness. Likewise, food and drink play an important role in drama, especially on stage. In the works of Sam Shepard, the playwright often makes eating and drinking an important and significant activity, something not only used to achieve realism but also to accentuate the action on stage.

In the same way, food is used in poetry as a sensual and sensory object. Specifically focusing on the role of fruit in poetry, Carol E. Dietrich notes that it often represents nature, offering the poet an objective symbol of the presence of God. Among fiction writers, Ernest Hemingway was noteworthy for his ability to create a particular mood though his fictional accounts of food. Hemingway often had his expatriate characters eat native foods, allowing them emotional access to the world they were inhabiting.

Dining rituals often provide a framework that both reflects and expresses human desires and behaviors. Many authors, Edith Wharton primary among them, have used the ritual of dining to present the powerful conflicts that simmer underneath the surface of order. This is also evident in Shakespeare’s Macbeth or George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire.

Food metaphors are often used to characterize people and their status in society. This is evident in the works of Toni Morrison and Gloria Naylor, who use food images to explore the struggle for an African-American identity. Food has been acknowledged as a key indicator of ethnicity. In their essay on the role of food, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Claude Fischler demonstrated that though the domain of food includes appetite, desire, and pleasure, it also serves as a reference point for society’s structure and world vision. Food and its related concerns with feminine identity and domesticity have been given a central place in many works of women’s literature. For example, authors such as Margaret Atwood have used food and eating disorders to address issues of gender, language, and sexual politics, as well as social dislocation.

Food thus does not limit itself to a mere breakdown into glucose chains or release of some definite amount of energy. It is not just a means for keeping cells working but encompasses much more. Food is a cycle of creation, patience, harvest, and consumption, to satiate not just the body but the very roots of our existence. Forms, styles, and media may differ, but the depiction of food will continue, in mesmerizing works of color or beautiful tales of ink, in culinary doctrines or personal notebooks. Truly, food is a celebration of life.

Bibliography

- Atwood, Margaret (1969) The Edible Woman. McClelland and Stewart

- Carroll, Lewis (1866) Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Macmillan

- Graham, Kenneth (1908) The Wind in the Willows. Methuen

- Hemingway, Ernest (1926) The Sun Also Rises. Scribner’s

- Hils Orford, E. (2013) Food in the Arts – A Look at Artistic Use of Food Over the Millennia. Decoded Past

- Hirsch Lent, M (2016) The Secret Meaning of Food in Art. The Smithsonian

- Meahger, J. (2012) Food and Drink in European Painting, 1400-1800. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

- Porter, Katherine Anna (1930) Flowering Judas and Other Stories. Penguin

- Sendak, Maurice (1963) In The Night Kitchen. Harper & Row

- Shepard, Sam (1964) 4H Club. The Unseen Hand and Other Plays, Bobbs Merrill, Indianapolis, 1971

SAYANTAN BASU is a Marine Engineering Trainee Cadet and an ardent lover of books and literature. He draws inspiration from authors around the globe and has participated in international collaborations like Rivers of the World, a Thames Festival Project.

Leave a Reply