Kelley Yuan

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

|

|

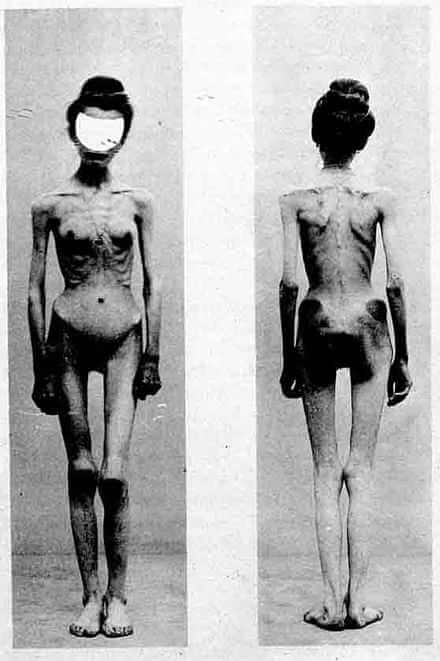

Anorexia nervosa. Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière. “Un cas d’anorexie hysterique” 1900. |

Xylophone ribs and sunken cheeks. A body desperate for food paired with a mind determined to starve. Here lies anorexia nervosa’s cruel paradox, of a body betrayed and a brain allowing it to waste away. The protest anorexic patients put up against eating, even as they lose hair and muscle, speaks to how differently they see food and the results of starvation.

Eating evolves from a way to sustain energy into a means to obtain other goals. Patients have found that anorexia grants them a new level of control they have never held before, over their own lives as well as their friends and family. The power to regulate when and how much they eat lets them control the shape of their bodies, changing situations where they once felt powerless.1

In Anorexics on Anorexia, one survivor describes how she used her starving frame to hold her family together. “The longer I did not eat, the more attention my parents gave me and the less time they spent arguing. I felt happier because they were not so angry at each other all the time, but I was worried that if I ate they would stop looking after me and would start arguing again.” Despite the sharp hunger pangs and fatigue, she continued, knowing her weak appearance warranted attention. “I had to look pale so that my parents would know I was ill. My hands were often very cold and looked yellow. This concerned my teacher too. My friends started saying I looked thin. They often looked after me and protected me. I liked that. I liked being the smallest person in the class. It made me feel important.” In a world where she once felt helpless and unnoticed at home and at school, the girl felt in control by starving herself. The newfound attention only encouraged her efforts.

While restricted eating brings some patients attention, others find starving a refuge from other stressors. Another patient writes, “The list [of things that worried me] was endless, as was the anxiety, but miraculously it had all vanished and all that occupied my thoughts was food. Food quickly became the main focus of my life. It was as if nothing else mattered.”1 The habit of tight dieting becomes an obsession to displace previous anxiety-inducers and fears.

Truly no other word can describe it but obsession. An adult survivor recalls anorexia’s innocuous beginnings as a mere elimination game that stretched into a compulsive list of rules. “The game went like this: first, stop eating sweets. Second, blot sauces, oils and dressings with paper towels while no one was looking. Third, count grams of fat, reject any food with over 3 grams, and keep a calorie tally in the back of your math notebook (where, if someone found it, they’d assume it was just math).”2 The diets of many more patients dwindle to extreme limits—for one, no more than a few mouthfuls of bran flakes and a few cups of black tea per day.1 “I would even think twice before licking a postage stamp for fear of any sugar coating on the gum!”

The starving mind’s obsession with food, however, is not limited to only anorexic patients. Even in healthy volunteers, this compulsion was induced and first documented in Ancel Keys’ landmark Minnesota study in 1950. Healthy men, upon starvation, soon hoarded cookbooks, dreamed of food, and developed eating rituals that persisted even after the experiment ended.3 Though a predominantly psychological disorder, anorexia nervosa clearly has physiological beginnings. Evidence suggests that this compulsiveness toward food stems from starvation-induced changes in the brain—particularly in the ventral striatum, a reward system region that forms habits in response to reinforcements.4

Arguably, there is no better reinforcement than the sense of achievement and satisfaction from losing weight. Says one recovering patient, “I found a great sense of achievement in being able to refuse all the ‘fattening’ foods I was offered. It put me on a tremendous high. This elation made all the periods of intense starvation worthwhile.”1 More survivors attest to the thrill. “My problems seemed out of my control but what I ate and what I weighed was within my control. I hated life at school and I hated life at home. But what I did enjoy was losing weight.”1 Weight loss becomes the ultimate accomplishment and a skill anorexic people hone to the extreme. “It was an exciting feeling because I felt, like, at the time that was the only thing I was good at,” recalls a survivor working with Project Heal. “So it gave me a sense of empowerment.”5 Some go as far as admiring anorexia’s persistent push to lose weight like the motivation of a friend. “I liked my friend’s [anorexia’s] focus and discipline. ‘Mind over matter,’ she chanted. I liked that idea. It meant success, achievement, overcoming.”6

Given the rewarding thrill of weight loss, the habit of dropping pounds usually accelerates into a form of addiction. Scholars have noticed the parallels between anorexia nervosa and substance abuse. Like a drug addiction, anorexia centers on a habitual behavior (starvation) that changes a person’s mental and physical state. However unpleasant the sensation at first, with enough reinforcement, the behavior comes to feel “right.” And despite how harmful the behavior clearly is, both the anorexic person and the addict will vehemently deny the problem—a response that markedly distinguishes anorexia from other neurotic disorders, where patients tend to exaggerate abnormal behaviors.7 One survivor admits, “There was no real reason why I wanted to lose weight. I think I had become addicted to it—addicted to the high I got from starvation and from seeing the scales go down and down.”1

The addiction to plummeting weight may also accompany an addiction to the personality changes caused by extensive hunger. Going Hungry: Writers on Desire, Self-Denial, and Overcoming Anorexia recounts the psychological changes some patients sought. “Being hungry kept me awake, alert, and focused . . . My mood grew darker as time went on, but for a while, I enjoyed enough highs to be protective of my strange eating habits. Like a lot of people addicted to a drug, I liked the person I was when I was hungry. She was intense, creative, dramatic: the opposite of the pale, subdued little girl I had been at eleven.”8 Her thoughts echo those of many contemporary anorexics, who see their bodies as reminders of a detested or shameful self, undesirable relics to reject or change.9

This intense dislike of their bodies colors the dialogue anorexics use to describe the pain they feel from eating. “My body hung below my head like a shaking, weak, and fleshy thing. It made frequent calls for food, becoming a bloated, bulging, aching presence when I ate. This was the wrong kind of pain; the pain of fullness, indulgence, and weakness. I wanted to be rid of my body’s messy, fatty spread and out-of-control demands . . . My body was the physical part of me that lived below my cranium.”6 The body stands as a separate entity from the self—a mere vehicle and a nuisance that the patient does not see as a part of herself worth caring for.

Stories like these from patients and survivors reveal how the psychological underpinnings of anorexia nervosa are what profoundly shape eating behavior. In the earlier ages of human history, people fasted as a means of penance and purification, often in a gesture of religious devotion. In contrast, contemporary anorexics are motivated to fast by unmet psychological needs. Interestingly, cases of anorexia all but vanished during the famine, siege, and desolation of Europe’s Dark Ages.9 Historians similarly noticed that zero cases of anorexia arose in post-World War II Italy, a period when the government imposed a series of strict food restrictions. Only after Italy recovered and after food returned to abundance did reports of anorexia resurface.10 The findings suggest that only when food becomes plentiful enough to forgo can the voluntary refusal to eat make a psychological statement.

At its core, anorexia’s psychological goals alter a person’s relationship with food and their bodies. Food becomes the one aspect in life they can control, up to a point of obsession where it can block out other stressors. Food is not rejected for its taste or inherent qualities but for what it represents: fatness, weak willpower, and obstacle to the ideal body. Likewise, hunger represents progress, a sign that starvation efforts are working. While most people treat hunger as an uncomfortable problem, anorexics see it as a solution and a rewarding sensation. It is no surprise, then, that when anorexics are forced to eat, they fight back because they fear caving in to a weakness, having their hard work sabotaged, and losing any psychological gains that came with their newfound weight loss. Disdain for their bodies justifies their starving and lets them endure the emaciation that would otherwise compel others to eat again. Perhaps in this regard, anorexia plays its most sinister card: turning food into fear and atrophy into accomplishment.

References

- Shelley, Rosemary. Anorexics on Anorexia. London: Jessica Kingsley, 1997.

- Fogarty, Lisa. 2018. “When Anorexics Grow Up.” The New York Times. The New York Times. January 11. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/11/well/live/anorexia-eating-disorders-adults-anorexic-aging.html.

- Kalm, Leah M., and Richard D. Semba. 2005. “They Starved So That Others Be Better Fed: Remembering Ancel Keys and the Minnesota Experiment.” The Journal of Nutrition 135 (6): 1347–52. doi:10.1093/jn/135.6.1347.

- Godier, Lauren R., and Rebecca J. Park. “Compulsivity in Anorexia Nervosa: A Transdiagnostic Concept.” Frontiers in Psychology 5 (2014). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00778.

- Haberman, Clyde. 2017. “In a Deadly Obsession, Food Is the Enemy.” The New York Times. The New York Times. December 3. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/03/us/in-a-deadly-obsession-food-is-the-enemy.html

- Lucas, Grace. 2018. “Body Matters.” Hektoen International. April 2. http://hekint.org/2017/12/08/body-matters/

- Brumberg, Joan Jacobs. 2001. Fasting Girls: the History of Anorexia Nervosa. New York: Random House.

- Taylor, Kate. 2008. Going Hungry: Writers on Desire, Self-Denial, and Overcoming Anorexia. New York: Anchor Books.

- Bemporad, Jules R. 1996. “Self-Starvation through the Ages: Reflections on the Pre-History of Anorexia Nervosa.” International Journal of Eating Disorders19 (3): 217–37. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199604)19:3<217::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-p.

- Selvini-Palazzoli, Mara. “Anorexia Nervosa: A Syndrome of the Affluent Society.” Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review 22, no. 3 (September 1, 1985): 199-205. doi:10.1177/136346158502200308. Translated from Italian by V. F. DiNicola.

KELLEY YUAN is a medical student at Sidney Kimmel Medical College. She explores bookstores and hunts for hot wing parlors when she should be studying for exams.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 1– Winter 2019

Leave a Reply